Politics

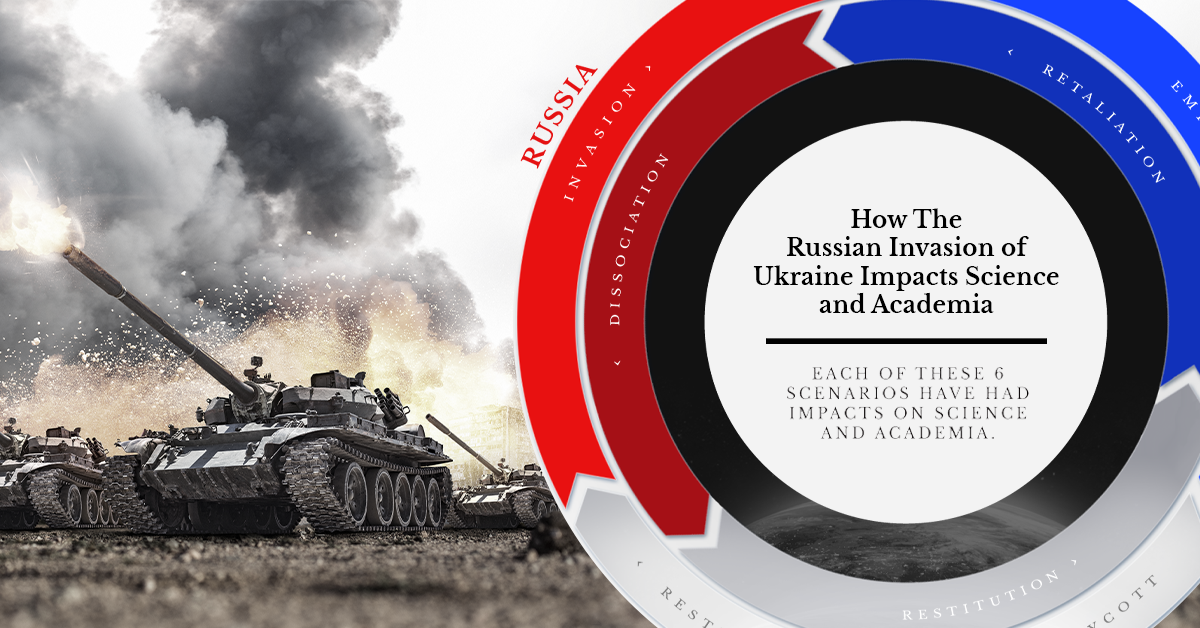

How the Russian Invasion of Ukraine Impacts Science and Academia

One Year of War

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded the eastern territories of Ukraine, claiming ownership of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. This began one of the largest military conflicts in modern European history.

After a year of casualties, structural devastation, and innumerable headlines, the conflict drags on. Many report the impacts to the economy, social demographics, and international relationships, but how do science and academia fair in the throes of war?

Within the actions and responses of the conflict, we take a look at how six key scenarios globally shape science.

War’s Material Impacts to Science

1. Russia Invades Ukraine

The assault to research infrastructure in Ukraine is devastating.

Approximately 27% of buildings are damaged or destroyed. The country’s leading scientific research centers, like the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, or the world’s largest decameter-wavelength radio telescope, are in ruins.

While the majority of research centers remain standing, many are not operating. Amidst rolling blackouts and disruptions, a dramatic decrease in research funds (as large as 50%) has cut back scientific activity in the country.

Rebuilding efforts are underway, but the extent to which it will return to its former capacity remains to be seen.

2. Ukraine Fights Back

As research funds have been redirected to the military, and scientists, too, have pivoted in a similar way. Martial law and general mobilization have enlisted male researchers, especially those with military experience and those within the 18-60 age range.

Women were exempt until July 2022. Those with degrees in chemistry, biology, and telecommunications were required to enter the military registry.

For both men and women researchers alike, these requirements meant staying in the country for the remainder of the year. Extensions for mobilization have subsided as of February 19th, 2023.

Social Impacts of War to Science

3. Western Leaders Exclude Russia

One year ago, scientists and institutions around the world immediately launched into protest against Russia’s escalation:

- The European Commission agreed to cease payments to Russian participants and to not renew contract agreements for Horizon Europe

- The $300-million, MIT-led Skoltech program was dissolved one day after the war began, with no foreseeable restart in the future

- Various governments and research councils in the European Union froze collaborations and discouraged working with Russian institutions

- The European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, barred all Russian observers and will dismiss almost 8% of its workers—about 1,000 Russian scientists—hen contracts expire later this year

These condemnations, and more, remain in effect today and are emboldened by what has come to be known as a “scientific boycott”.

Journal publishers around the world imposed some of their own sanctions on Russian institutions and scientists in light of this boycott. These range from prohibiting Russian manuscript submissions (Elsevier’s Journal of Molecular Structure) to scrubbing journal indices of Russian papers and authors.

4. Russia Dissociates from the West

As a response to the sanctions imposed on the Russian economy, Russia ceases to sell natural gas to most of Europe. Institutions are reassessing their usage and dependence on Russian energy, but alternatives are not yet affordable.

The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, home to the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, is struggling with rising electricity costs. CERN, for instance, has already cut its data collection for the year by two weeks in order to save money.

This makes it difficult for pre-war projects to continue collaborating with Russia. As a result, there are questions about how withdrawals may be affecting Russian science, too.

For now, that remains relatively unknown, though some have guesses. Young scientists, many barred from attending international conferences and meetings, may seek employment or opportunity elsewhere to develop their careers. Some speculate a “brain drain” effect may occur, similar to the academic fallout of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s.

How Russia will participate in pre-war international research collaborations is still unknown. For now, a number of pre-war projects ranging from the Arctic to the fire-prone wilds of northern Russia are on hold. All of these scenarios paint a concerning picture about the progress of research.

There are indications that Russian scientific collaboration may already be shifting eastward.

Philanthropic Impacts of War to Science

5. New Homes for Ukrainian Science

Finding support for Ukrainians emigrating from the conflict is difficult, but not impossible. Though many Ukrainians scientists remain in the country making the best of a difficult situation, approximately 6,000 are now living abroad.

Most Ukrainian emigrants are now living in Poland and Germany. Some scientists continue to work remotely, supporting projects at their home institutions or with new research programs they’ve found since relocating.

These success stories are thanks to the work of a number of ad-hoc mobilizations that help keep researchers working in the European cooperation. Groups like MSC4Ukraine help postdoc students and researchers find new opportunities across Europe. Social media trends like #Science4Ukraine help connect researchers to other supportive movements.

6. The International Rebuilding of Ukrainian Science

Various research institutions have also lent support to the survival and rebuilding of science in Ukraine:

- The largest science prize, the Breakthrough Prize, recently donated $3 million to fund research programs and reconstruction efforts

- Federal research councils, like those in Netherlands and Switzerland, also have programs to formally support displaced scientists and researchers

- The European Union is investigating new funding schemes that could repurpose almost €320 billion of frozen Russian Federal Reserves

No Consensus on Boycott

While the Western front seems united in it’s condemnation of the war, the international science community isn’t in total agreement with a science boycott.

Some scientists argue that excluding Russian scientists—especially those who have vocalized their disdain for the war—serves to punish unrelated individuals. This fractures the benefits of international scientific exchange.

Others, especially those in countries who are economically dependent on Russia, have remained silent or even supported the invasion. In these cases, Russia’s science initiatives may lean more heavily in their direction.

It’s easy to appreciate how war complicates many different angles of the global research ecosystem. After one year, how things will turn out remains a mystery. But one thing is for certain: science adapts and progresses even in the bleakest times. For now, supporting all efforts to reduce conflict remains in science’s best interests.

Full sources here

Economy

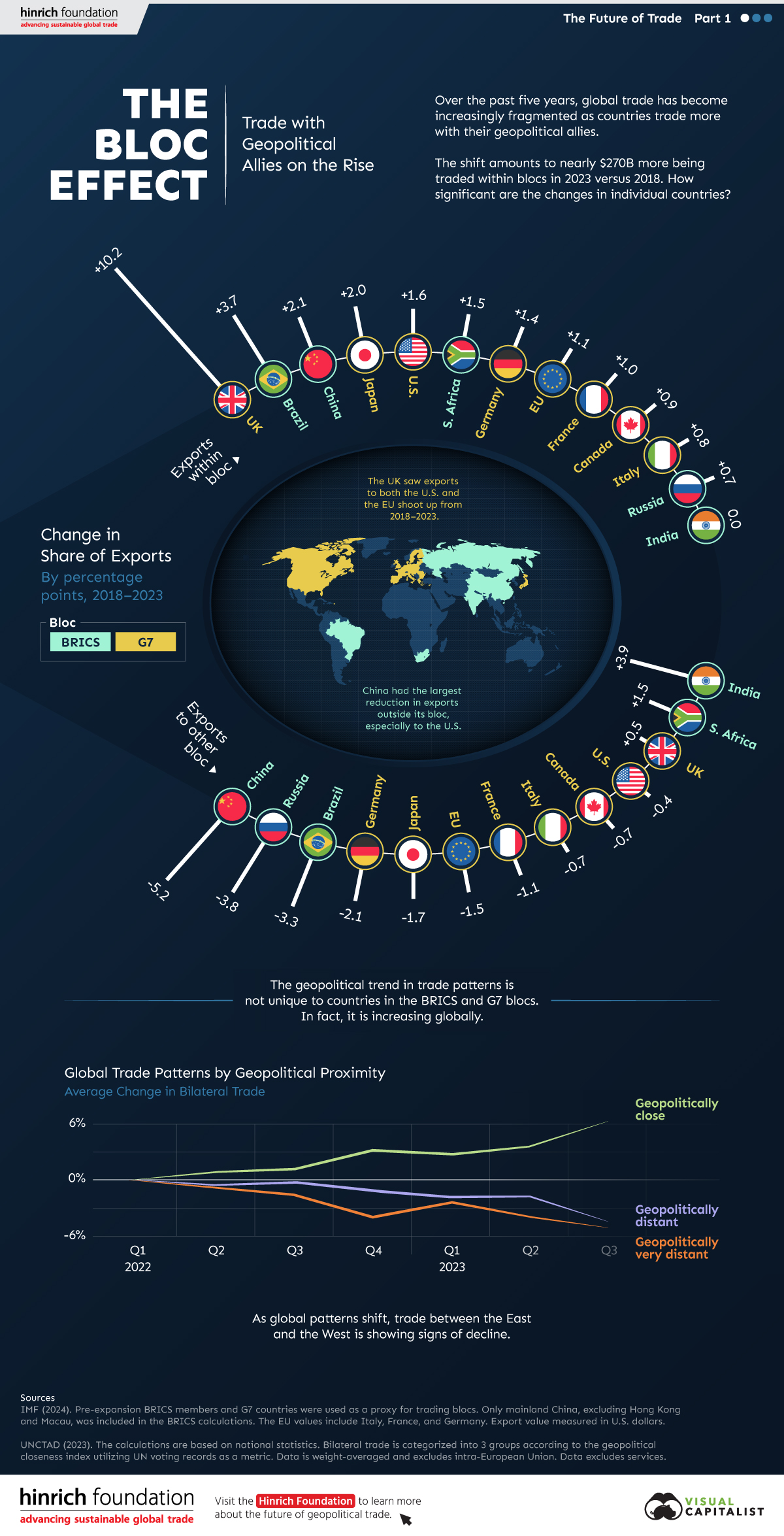

The Bloc Effect: International Trade with Geopolitical Allies on the Rise

Rising geopolitical tensions are shaping the future of international trade, but what is the effect on trading among G7 and BRICS countries?

The Bloc Effect: International Trade with Allies on the Rise

International trade has become increasingly fragmented over the last five years as countries have shifted to trading more with their geopolitical allies.

This graphic from The Hinrich Foundation, the first in a three-part series covering the future of trade, provides visual context to the growing divide in trade in G7 and pre-expansion BRICS countries, which are used as proxies for geopolitical blocs.

Trade Shifts in G7 and BRICS Countries

This analysis uses IMF data to examine differences in shares of exports within and between trading blocs from 2018 to 2023. For example, we looked at the percentage of China’s exports with other BRICS members as well as with G7 members to see how these proportions shifted in percentage points (pp) over time.

Countries traded nearly $270 billion more with allies in 2023 compared to 2018. This shift came at the expense of trade with rival blocs, which saw a decline of $314 billion.

Country Change in Exports Within Bloc (pp) Change in Exports With Other Bloc (pp)

🇮🇳 India 0.0 3.9

🇷🇺 Russia 0.7 -3.8

🇮🇹 Italy 0.8 -0.7

🇨🇦 Canada 0.9 -0.7

🇫🇷 France 1.0 -1.1

🇪🇺 EU 1.1 -1.5

🇩🇪 Germany 1.4 -2.1

🇿🇦 South Africa 1.5 1.5

🇺🇸 U.S. 1.6 -0.4

🇯🇵 Japan 2.0 -1.7

🇨🇳 China 2.1 -5.2

🇧🇷 Brazil 3.7 -3.3

🇬🇧 UK 10.2 0.5

All shifts reported are in percentage points. For example, the EU saw its share of exports to G7 countries rise from 74.3% in 2018 to 75.4% in 2023, which equates to a 1.1 percentage point increase.

The UK saw the largest uptick in trading with other countries within the G7 (+10.2 percentage points), namely the EU, as the post-Brexit trade slump to the region recovered.

Meanwhile, the U.S.-China trade dispute caused China’s share of exports to the G7 to fall by 5.2 percentage points from 2018 to 2023, the largest decline in our sample set. In fact, partly as a result of the conflict, the U.S. has by far the highest number of harmful tariffs in place.

The Russia-Ukraine War and ensuing sanctions by the West contributed to Russia’s share of exports to the G7 falling by 3.8 percentage points over the same timeframe.

India, South Africa, and the UK bucked the trend and continued to witness advances in exports with the opposing bloc.

Average Trade Shifts of G7 and BRICS Blocs

Though results varied significantly on a country-by-country basis, the broader trend towards favoring geopolitical allies in international trade is clear.

Bloc Change in Exports Within Bloc (pp) Change in Exports With Other Bloc (pp)

Average 2.1 -1.1

BRICS 1.6 -1.4

G7 incl. EU 2.4 -1.0

Overall, BRICS countries saw a larger shift away from exports with the other bloc, while for G7 countries the shift within their own bloc was more pronounced. This implies that though BRICS countries are trading less with the G7, they are relying more on trade partners outside their bloc to make up for the lost G7 share.

A Global Shift in International Trade and Geopolitical Proximity

The movement towards strengthening trade relations based on geopolitical proximity is a global trend.

The United Nations categorizes countries along a scale of geopolitical proximity based on UN voting records.

According to the organization’s analysis, international trade between geopolitically close countries rose from the first quarter of 2022 (when Russia first invaded Ukraine) to the third quarter of 2023 by over 6%. Conversely, trade with geopolitically distant countries declined.

The second piece in this series will explore China’s gradual move away from using the U.S. dollar in trade settlements.

Visit the Hinrich Foundation to learn more about the future of geopolitical trade

-

Economy2 days ago

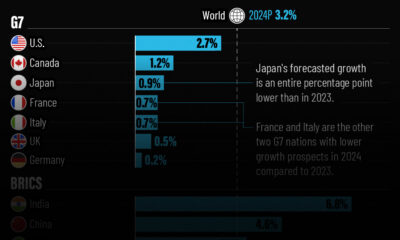

Economy2 days agoEconomic Growth Forecasts for G7 and BRICS Countries in 2024

The IMF has released its economic growth forecasts for 2024. How do the G7 and BRICS countries compare?

-

United States2 weeks ago

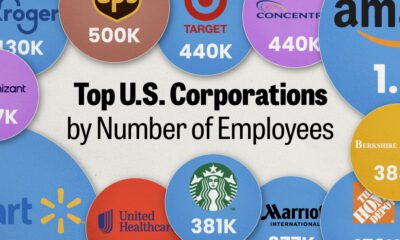

United States2 weeks agoRanked: The Largest U.S. Corporations by Number of Employees

We visualized the top U.S. companies by employees, revealing the massive scale of retailers like Walmart, Target, and Home Depot.

-

Economy2 weeks ago

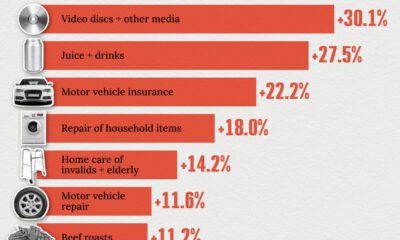

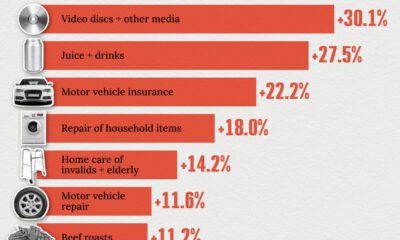

Economy2 weeks agoWhere U.S. Inflation Hit the Hardest in March 2024

We visualized product categories that saw the highest % increase in price due to U.S. inflation as of March 2024.

-

Economy4 weeks ago

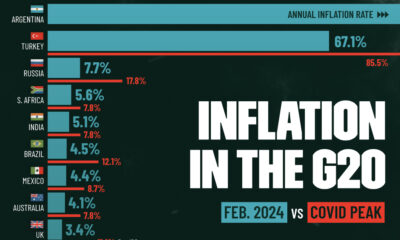

Economy4 weeks agoG20 Inflation Rates: Feb 2024 vs COVID Peak

We visualize inflation rates across G20 countries as of Feb 2024, in the context of their COVID-19 pandemic peak.

-

Economy1 month ago

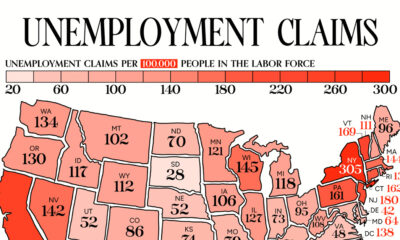

Economy1 month agoMapped: Unemployment Claims by State

This visual heatmap of unemployment claims by state highlights New York, California, and Alaska leading the country by a wide margin.

-

Economy2 months ago

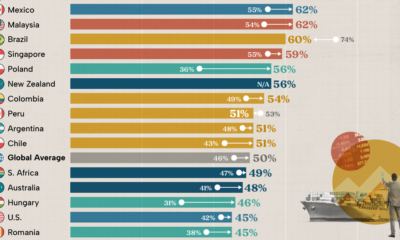

Economy2 months agoConfidence in the Global Economy, by Country

Will the global economy be stronger in 2024 than in 2023?

-

Energy1 week ago

Energy1 week agoThe World’s Biggest Nuclear Energy Producers

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

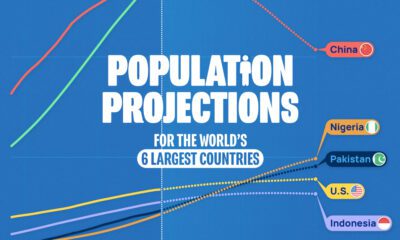

Demographics2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoWhere U.S. Inflation Hit the Hardest in March 2024