Markets

Visualized: A Global Risk Assessment of 2022 and Beyond

Visualized: A Global Risk Assessment of 2022 and Beyond

Since the start of the global pandemic, we’ve been navigating through tumultuous waters, and this year is expected to be as unpredictable as ever.

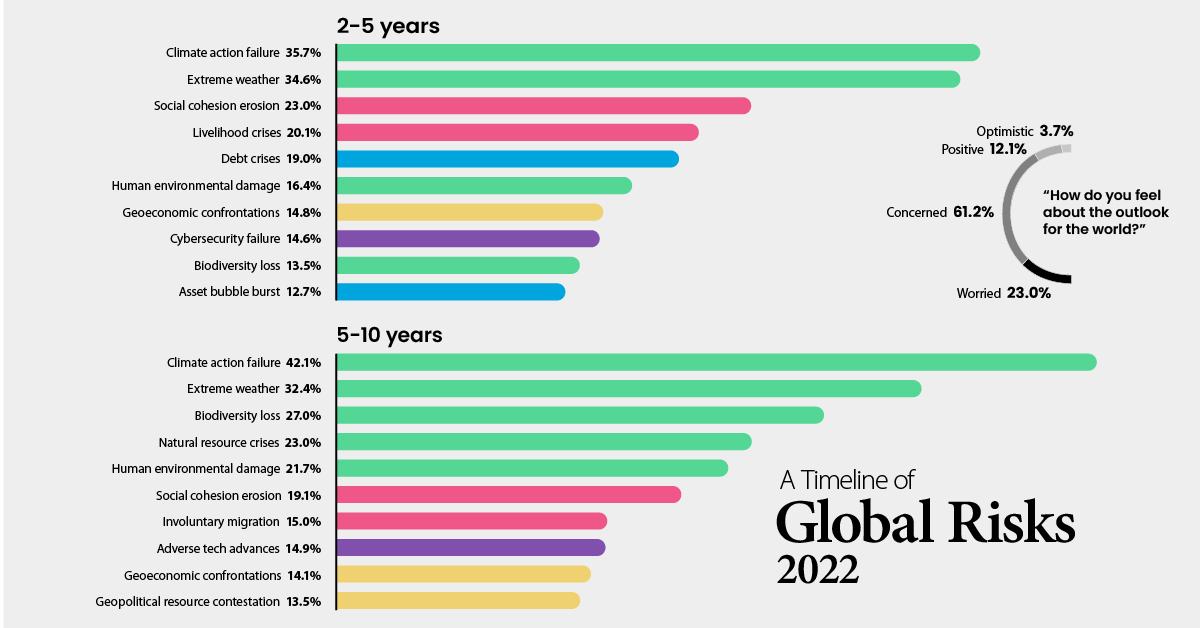

In the latest annual edition of the Global Risks Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF), it was found that a majority of global leaders feel worried or concerned about the outlook of the world, and only 3.7% feel optimistic.

Ever year, the report identifies the top risks facing the world, as identified by nearly 1,000 surveyed experts and leaders across various disciplines, organizations, and geographies.

What global risks are leaders and experts most concerned about, and which ones are posing imminent threats? Let’s dive into the key findings from the report.

Methodology for WEF’s Global Risk Assessment

In the survey, respondents were asked to compare 37 different risks, which were broken down into five categories: economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal, and technological.

To get a sense of which risks were seen as more urgent than others, respondents were asked to identify when they believed these threats would become a serious problem to the world, based on the following timeframes:

- Short-term threats: 0-2 years

- Medium-term threats: 2-5 years

- Long-term threats: 5-10 years

By categorizing global risks into these time horizons, it helps provide a better idea of the problems that decision makers and governments may have to deal with in the near future, and how these risks may interrelate with one another.

Short-Term Risks

When it comes to short-term threats, respondents identified societal risks such as “the erosion of social cohesion” and “livelihood crises” as the most immediate risks to the world.

| Timeframe | Category | Threat | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 years | 🟢 Environmental | Extreme weather | 31.1% |

| 0-2 years | 🔴 Societal | Livelihood crises | 30.4% |

| 0-2 years | 🟢 Environmental | Climate action failure | 27.5% |

| 0-2 years | 🔴 Societal | Social cohesion erosion | 27.5% |

| 0-2 years | 🔴 Societal | Infectious diseases | 26.4% |

| 0-2 years | 🔴 Societal | Mental health deterioration | 26.1% |

| 0-2 years | 🟣 Technological | Cybersecurity failure | 19.5% |

| 0-2 years | 🔵 Economic | Debt crises | 19.3% |

| 0-2 years | 🟣 Technological | Digital inequality | 18.2% |

| 0-2 years | 🔵 Economic | Asset bubble burst | 14.2% |

These societal risks have worsened since the start of COVID-19. And as emerging variants threaten our journey towards normalcy, the pandemic continues to wreak havoc worldwide, with no immediate signs of slowing down.

According to respondents, one problem triggered by the pandemic is rising inequality, both worldwide and within countries.

Many developed economies managed to adapt as office workers pivoted to remote and hybrid work, though many industries, such as hospitality, still face significant headwinds. Easy access to vaccines has helped these countries mitigate the worst effects of outbreaks.

Regions with low access to vaccines have not been so fortunate, and the economic divide could become more apparent as the pandemic stretches on.

Medium-Term Risks

A majority of respondents believe we’ll continue to struggle with pandemic-related issues for the next three years. Because of this, the medium-term risks identified by respondents are fairly similar to the short-term risks.

| Timeframe | Category | Threat | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-5 years | 🟢 Environmental | Climate action failure | 35.7% |

| 2-5 years | 🟢 Environmental | Extreme weather | 34.6% |

| 2-5 years | 🔴 Societal | Social cohesion erosion | 23.0% |

| 2-5 years | 🔴 Societal | Livelihood crises | 20.1% |

| 2-5 years | 🔵 Economic | Debt crises | 19.0% |

| 2-5 years | 🟢 Environmental | Human environmental damage | 16.4% |

| 2-5 years | 🟡 Geopolitical | Geoeconomic confrontations | 14.8% |

| 2-5 years | 🟣 Technological | Cybersecurity failure | 14.6% |

| 2-5 years | 🟢 Environmental | Biodiversity loss | 13.5% |

| 2-5 years | 🔵 Economic | Asset bubble burst | 12.7% |

The pressing issues caused by COVID-19 mean that many key governments and decision-makers are struggling to prioritize long-term planning, and no longer have the capacity to help out with global issues. For example, the UK government postponed its foreign aid target until at least 2024. If countries continue to prioritize themselves in an effort to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, the inequality gap could widen even further.

Respondents also worry about rising debt levels triggering a crisis. The debt-to-GDP ratio globally spiked by 13 percentage points in 2020, a figure that will almost certainly continue to rise in the near future.

Long-Term Risks

Respondents identified climate change as the biggest threat to humanity in the next decade.

| Timeframe | Category | Threat | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-10 years | 🟢 Environmental | Climate action failure | 42.1% |

| 5-10 years | 🟢 Environmental | Extreme weather | 32.4% |

| 5-10 years | 🟢 Environmental | Biodiversity loss | 27.0% |

| 5-10 years | 🟢 Environmental | Natural resource crises | 23.0% |

| 5-10 years | 🟢 Environmental | Human environmental damage | 21.7% |

| 5-10 years | 🔴 Societal | Social cohesion erosion | 19.1% |

| 5-10 years | 🔴 Societal | Involuntary migration | 15.0% |

| 5-10 years | 🟣 Technological | Adverse tech advances | 14.9% |

| 5-10 years | 🟡 Geopolitical | Geoeconomic confrontations | 14.1% |

| 5-10 years | 🟡 Geopolitical | Geopolitical resource contestation | 13.5% |

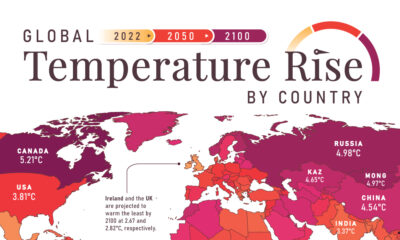

Climate inaction—essentially business as usual—could lead to a global GDP loss between 4% and 18%, with varying impacts across different regions.

Experts also pointed out that current decarbonization commitments made at COP26 last year still aren’t enough to slow warming to the 1.5°C goal set in the Paris Climate Agreement, so more action is needed to mitigate environmental risk.

That said, efforts to curb climate change and solve long-term issues will likely have negative short-term impacts on the global economy and society. So risk mitigation efforts need to be in place as we work to reach net-zero and ultimately slow down climate change.

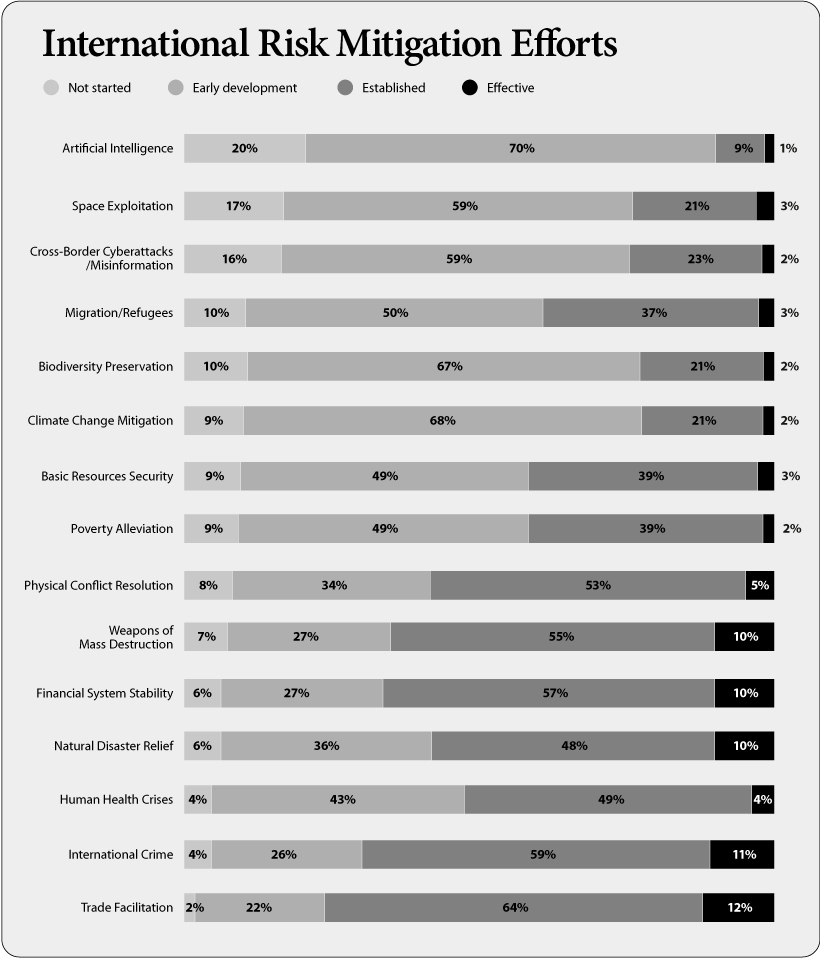

Risk Mitigation Efforts

People’s thoughts on risk mitigation were gauged in the WEF survey. Respondents were asked to identify which risks our world is most equipped to handle, and which ones they believe we’re less prepared for.

“Trade facilitation,” “international crime,” and “weapons of mass destruction” were risks that respondents felt we’ve effectively prepared for. On the flip side, “artificial intelligence” and “cross-border cyberattacks and misinformation” are areas where most respondents think we’re most unprotected against.

As society becomes increasingly reliant on digital infrastructure, experts predict we will see an uptick in cyber attacks and cybercrime. New AI-enabled technologies that offer ransomware-as-a-service allow anyone to engage in cybercrime—even those without the technical knowledge needed to build malware.

How Do We Move Forward?

Based on the findings from this year’s survey, WEF identified five lessons that governments, businesses, and decision-makers should utilize in order to build resilience and prepare for future challenges:

- Build a holistic mitigation framework: Rather than focusing on specific risks, it’s helpful to identify the big-picture worst-case scenario and work back from there. Build holistic systems that protect against adverse outcomes.

- Consider the entire ecosystem: Examine third-party services and external assets, and analyze the broader ecosystem in which you operate.

- Embrace diversity in resilience strategies: Not all strategies will work across the board. Complex problems will require nuanced efforts. Adaptability is key.

- Connect resilience efforts with other goals: Many resilience efforts could benefit multiple aspects of society. For instance, efficient supply chains could strengthen communities and contribute to environmental goals.

- Think of resilience as a journey, not a destination: Remaining agile and vigilant is vital when building out resilience programs, as these efforts are new and require reflection in order to improve.

The next few years will be riddled with complex challenges, and our best chance at mitigating these global risks is through increased collaboration and consistent reassessment.

Markets

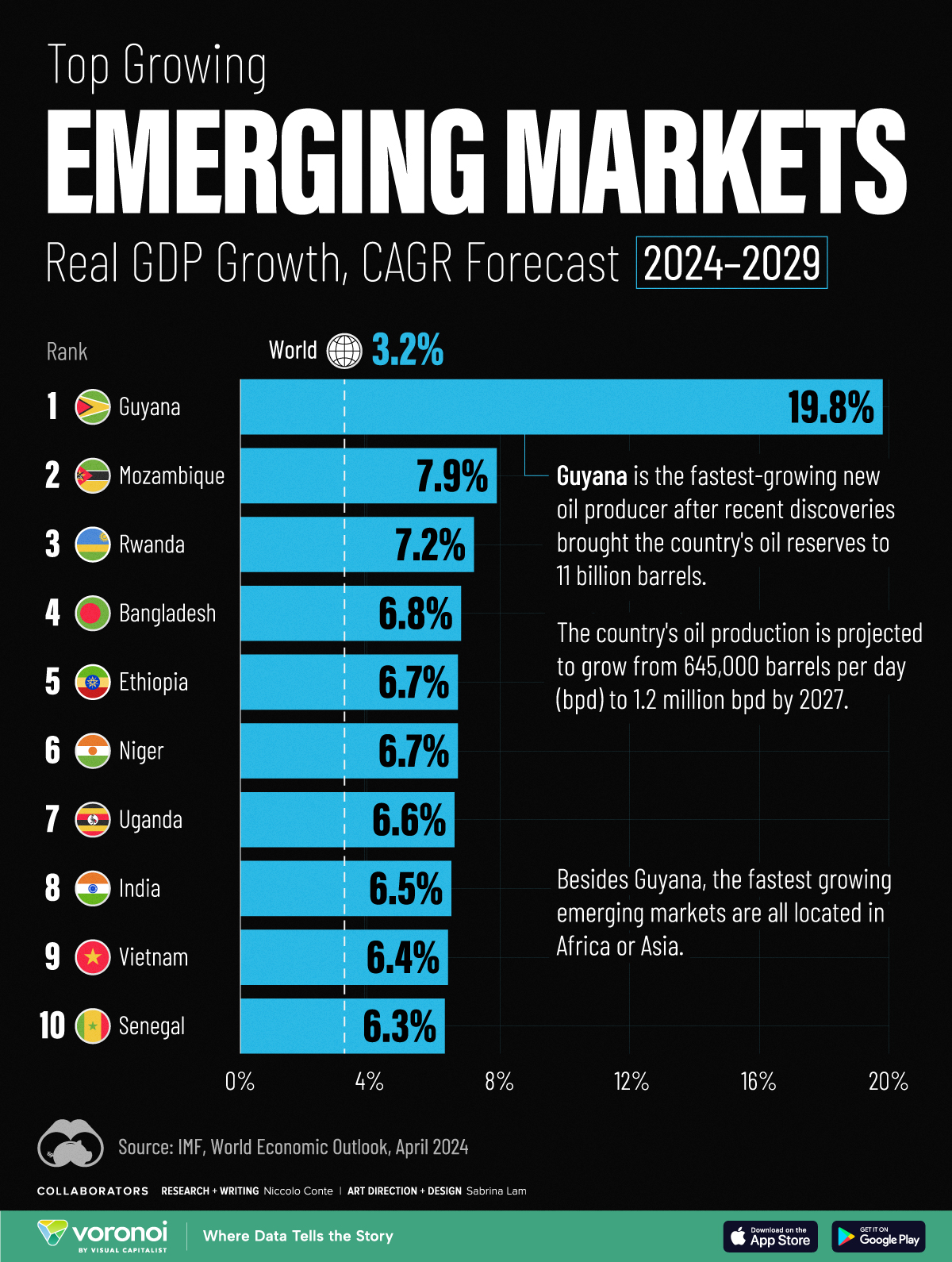

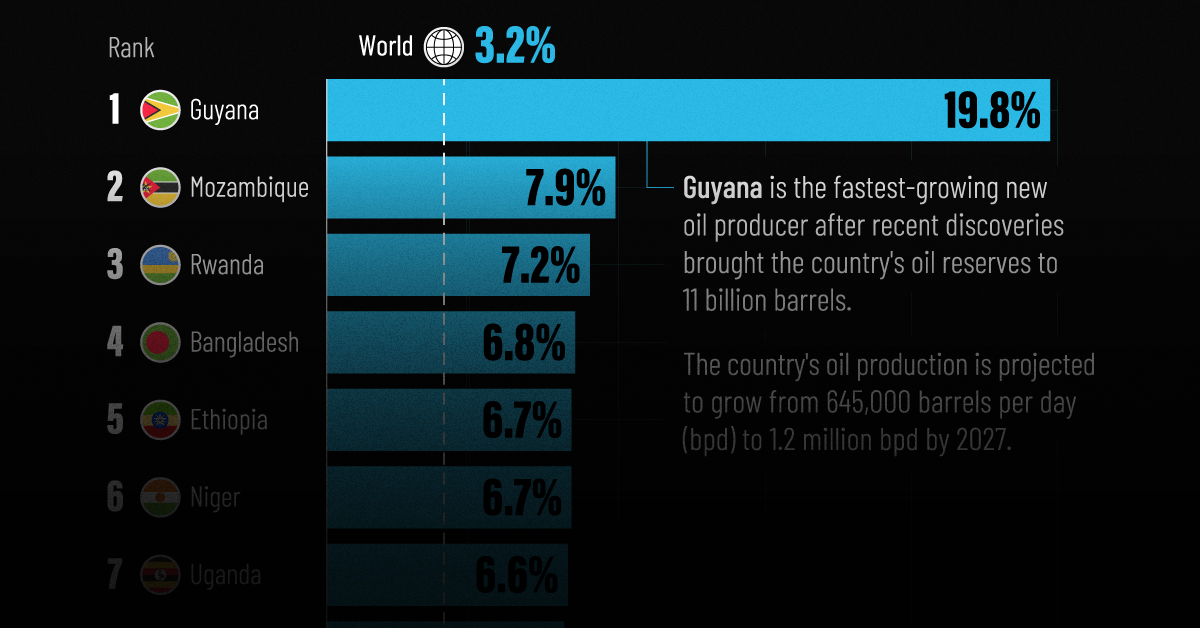

The World’s Fastest Growing Emerging Markets (2024-2029 Forecast)

Here are the emerging markets with the fastest projected growth rates over the next five years based on analysis from the IMF.

The World’s Fastest Growing Emerging Markets (2024-2029)

Large emerging markets are forecast to play a greater role in powering global economic growth in the future, driven by demographic shifts and a growing consumer class.

At the same time, many smaller nations are projected to see their economies grow at double the global average over the next five years due to rich natural resource deposits among other factors. That said, elevated debt levels do present risks to future economic activity.

This graphic shows the emerging markets with the fastest projected growth through to 2029, based on data from the International Monetary Fund’s 2024 World Economic Outlook.

Get the Key Insights of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

Want a visual breakdown of the insights from the IMF’s 2024 World Economic Outlook report?

This visual is part of a special dispatch of the key takeaways exclusively for VC+ members.

Get the full dispatch of charts by signing up to VC+.

Top 10 Emerging Markets

Here are the fastest-growing emerging economies, based on real GDP compound annual growth rate (CAGR) forecasts over the period of 2024-2029:

| Rank | Country | Projected CAGR (2024-2029) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 🇬🇾 Guyana | 19.8% |

| 2 | 🇲🇿 Mozambique | 7.9% |

| 3 | 🇷🇼 Rwanda | 7.2% |

| 4 | 🇧🇩 Bangladesh | 6.8% |

| 5 | 🇪🇹 Ethiopia | 6.7% |

| 6 | 🇳🇪 Niger | 6.7% |

| 7 | 🇺🇬 Uganda | 6.6% |

| 8 | 🇮🇳 India | 6.5% |

| 9 | 🇻🇳 Vietnam | 6.4% |

| 10 | 🇸🇳 Senegal | 6.3% |

As South America’s third-smallest nation by land area, Guyana is projected to be the world’s fastest growing economy from now to 2029.

This is thanks to a significant discovery of oil deposits in 2015 by ExxonMobil, which has propelled the country’s economy to grow by fourfold over the last five years alone. By 2028, the nation of just 800,000 people is projected to have the highest crude oil production per capita, outpacing Kuwait for the first time.

Bangladesh, where 85% of exports are driven by the textiles industry, is forecast to see the strongest growth in Asia. In fact, over the last 30 years, the country of 170 million people has not had a single year of negative growth.

In eighth place overall is India, projected to achieve a 6.5% CAGR in real GDP through to 2029. This growth is forecast to be fueled by population trends, public investment, and strong consumer demand.

Get the Full Analysis of the IMF’s Outlook on VC+

This visual is part of an exclusive special dispatch for VC+ members which breaks down the key takeaways from the IMF’s 2024 World Economic Outlook.

For the full set of charts and analysis, sign up for VC+.

-

Green7 days ago

Green7 days agoThe Carbon Footprint of Major Travel Methods

-

Debt2 weeks ago

Debt2 weeks agoHow Debt-to-GDP Ratios Have Changed Since 2000

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoThe Highest Earning Athletes in Seven Professional Sports

-

Science2 weeks ago

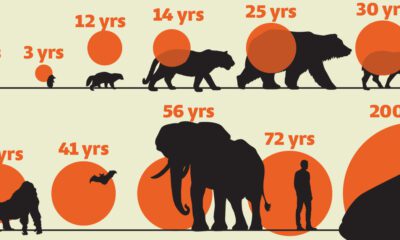

Science2 weeks agoVisualizing the Average Lifespans of Mammals

-

Brands2 weeks ago

Brands2 weeks agoHow Tech Logos Have Evolved Over Time

-

Energy2 weeks ago

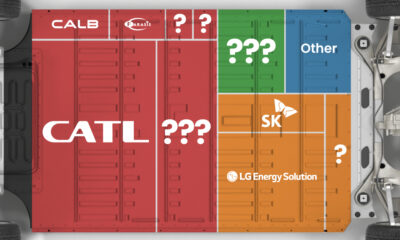

Energy2 weeks agoRanked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

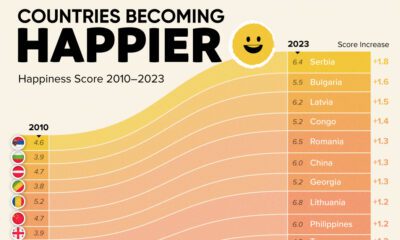

Demographics2 weeks agoCountries With the Largest Happiness Gains Since 2010

-

VC+2 weeks ago

VC+2 weeks agoVC+: Get Our Key Takeaways From the IMF’s World Economic Outlook