Misc

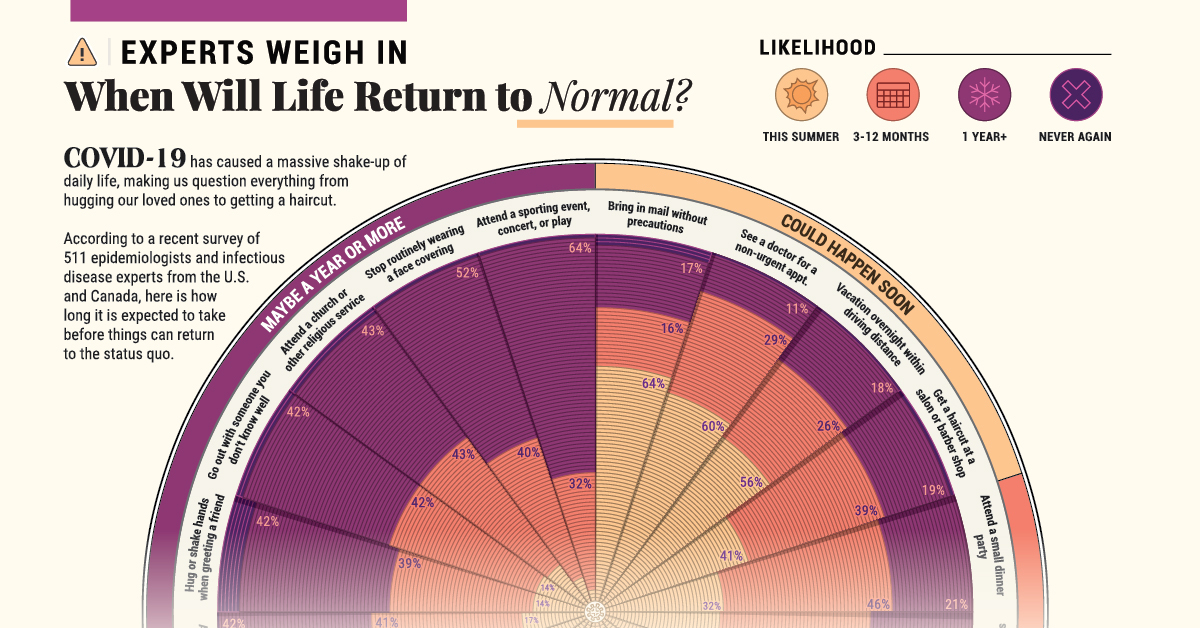

When Will Life Return to Normal?

When Will Life Return to Normal?

From battles on the front lines to social distancing from friends and family, COVID-19 has caused a massive shake-up of our daily lives.

After second-guessing everything from hugging our loved ones to delaying travel, there is one big question that everyone is likely thinking about: will we ever get back to the status quo? The answer may not be very clear-cut.

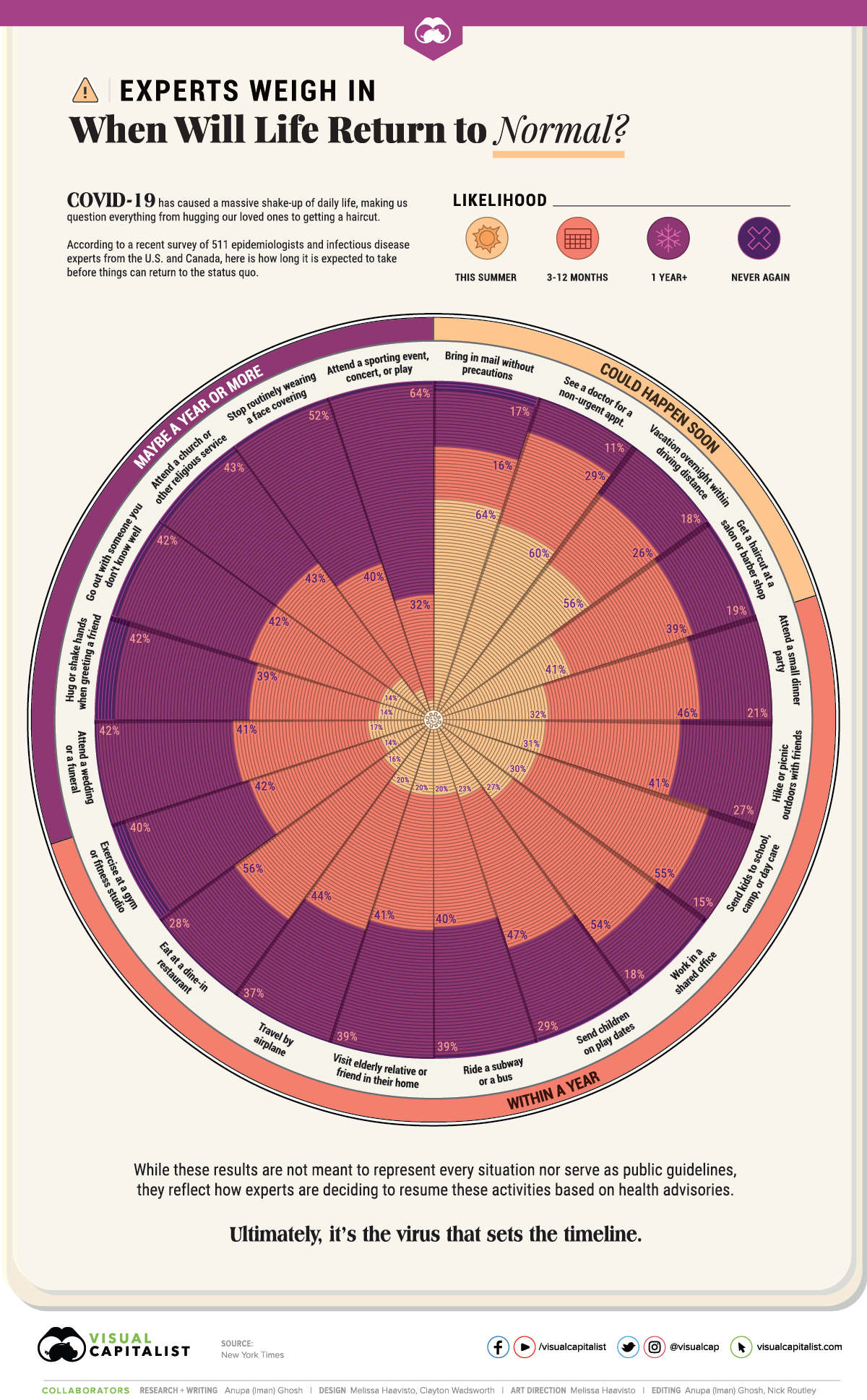

Today’s graphic uses data from New York Times’ interviews of 511 epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists from the U.S. and Canada, and visualizes their opinions on when they might expect to resume a range of typical activities.

Life in the Near Future, According to Experts

Specifically, this group of epidemiologists were asked when they might personally begin engaging in 20 common daily activities again.

The responses, based on the latest publicly available and scientifically-backed data, varied based on assumptions around local pandemic response plans. The experts also noted that their answers would change depending on potential treatments and testing rates in their local areas.

Here are the activities that a majority of professionals see starting up as soon as this summer, or within a year’s time:

| This summer | 3-12 months | +1 year | Never again | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 📬 Bring in mail without precautions | 64% | 16% | 17% | 3% |

| 👩⚕️ See a doctor for a non-urgent appointment | 60% | 29% | 11% | <1% |

| 🚗 Vacation overnight within driving distance | 56% | 26% | 18% | <1% |

| 💇♂️ Get a haircut at a salon or barber shop | 41% | 39% | 19% | 1% |

| 🥳 Attend a small dinner party | 32% | 46% | 21% | <1% |

| 🥾 Hike or picnic outdoors with friends | 31% | 41% | 27% | <1% |

| 🎒 Send kids to school, camp, or day care | 30% | 55% | 15% | <1% |

| 🏢 Work in a shared office | 27% | 54% | 18% | 1% |

| 👶 Send children on play dates | 23% | 47% | 29% | 1% |

| 🚌 Ride a subway or a bus | 20% | 40% | 39% | 1% |

| 👴 Visit elderly relative or friend in their home | 20% | 41% | 39% | <1% |

| ✈️ Travel by airplane | 20% | 44% | 37% | <1% |

| 🍽️ Eat at a dine-in restaurant | 16% | 56% | 28% | <1% |

| 🏋️ Exercise at a gym or fitness studio | 14% | 42% | 40% | 4% |

The urge to be outdoors is pretty clear, with 56% of those surveyed hoping to take a road trip before the summer is over. Meanwhile, 31% felt that they would be able to go hiking or have a picnic with friends this summer, citing the need for “fresh air, sun, socialization and a healthy activity” to help keep on top of their physical and mental health during this time.

Public transport and travel of any form is one aspect that has been put on hold, whether it’s by plane, train, or automobile. Many of the surveyed epidemiologists also lamented the strain the pandemic has had on relationships, as evidenced by the social situations they hope to restart sooner rather than later.

The worst casualty of the epidemic is the loss of human contact.

—Eduardo Franco, McGill University

On the other hand, there are certain activities that they considered too risky to engage in for the time-being. A large share are putting off attending celebrations such as weddings or concerts for at least a year or more, out of perceived social responsibility.

| This summer | 3-12 months | +1 year | Never again | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 👰⚰️ Attend a wedding or a funeral | 17% | 41% | 42% | <1% |

| 🤗🤝 Hug or shake hands when greeting a friend | 14% | 39% | 42% | 6% |

| 💞 Go out with someone you don't know well | 14% | 42% | 42% | 2% |

| 🛐 Attend a church or other religious service | 13% | 43% | 43% | 2% |

| 😷 Stop routinely wearing a face covering | 7% | 40% | 52% | 1% |

| 🎫 Attend a sporting event, concert, or play | 3% | 32% | 64% | 1% |

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that 6% of epidemiologists do not expect to ever hug or shake hands as a post-pandemic greeting. On top of this, over half consider masks necessary for at least the next year.

The Virus Sets the Timeline

Of course, these estimates are not meant to represent every situation. The experts also practically considered whether certain activities were avoidable or not—such as one’s occupation—which affects individual risk levels.

The answers [about resuming these activities] have nothing to do with calendar time.

—Kristi McClamroch, University at Albany

While many places are trickling out of lockdown and re-opening to support the economy, some officials are still warning against prematurely lifting restrictions before we fully have a handle on the virus and its spread.

VC+

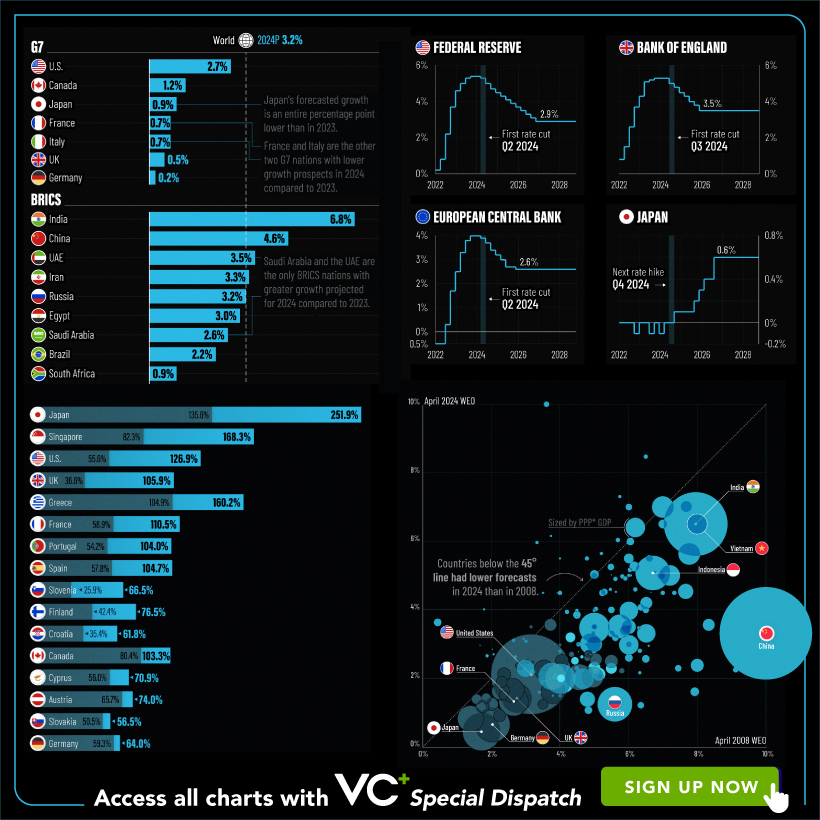

VC+: Get Our Key Takeaways From the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

A sneak preview of the exclusive VC+ Special Dispatch—your shortcut to understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook report.

Have you read IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook yet? At a daunting 202 pages, we don’t blame you if it’s still on your to-do list.

But don’t worry, you don’t need to read the whole April release, because we’ve already done the hard work for you.

To save you time and effort, the Visual Capitalist team has compiled a visual analysis of everything you need to know from the report—and our VC+ Special Dispatch is available exclusively to VC+ members. All you need to do is log into the VC+ Archive.

If you’re not already subscribed to VC+, make sure you sign up now to access the full analysis of the IMF report, and more (we release similar deep dives every week).

For now, here’s what VC+ members get to see.

Your Shortcut to Understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook

With long and short-term growth prospects declining for many countries around the world, this Special Dispatch offers a visual analysis of the key figures and takeaways from the IMF’s report including:

- The global decline in economic growth forecasts

- Real GDP growth and inflation forecasts for major nations in 2024

- When interest rate cuts will happen and interest rate forecasts

- How debt-to-GDP ratios have changed since 2000

- And much more!

Get the Full Breakdown in the Next VC+ Special Dispatch

VC+ members can access the full Special Dispatch by logging into the VC+ Archive, where you can also check out previous releases.

Make sure you join VC+ now to see exclusive charts and the full analysis of key takeaways from IMF’s World Economic Outlook.

Don’t miss out. Become a VC+ member today.

What You Get When You Become a VC+ Member

VC+ is Visual Capitalist’s premium subscription. As a member, you’ll get the following:

- Special Dispatches: Deep dive visual briefings on crucial reports and global trends

- Markets This Month: A snappy summary of the state of the markets and what to look out for

- The Trendline: Weekly curation of the best visualizations from across the globe

- Global Forecast Series: Our flagship annual report that covers everything you need to know related to the economy, markets, geopolitics, and the latest tech trends

- VC+ Archive: Hundreds of previously released VC+ briefings and reports that you’ve been missing out on, all in one dedicated hub

You can get all of the above, and more, by joining VC+ today.

-

Debt1 week ago

Debt1 week agoHow Debt-to-GDP Ratios Have Changed Since 2000

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Countries2 weeks ago

Countries2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

-

United States2 weeks ago

United States2 weeks agoWhere U.S. Inflation Hit the Hardest in March 2024

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoTop Countries By Forest Growth Since 2001

-

United States2 weeks ago

United States2 weeks agoRanked: The Largest U.S. Corporations by Number of Employees