Markets

The World’s Most Famous Case of Deflation

The World’s Most Famous Case of Deflation (Part 1 of 2)

The Money Project is an ongoing collaboration between Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals that seeks to use intuitive visualizations to explore the origins, nature, and use of money.

The Great Depression was the most severe economic depression ever experienced by the Western world.

It was during this troubled time that the world’s most famous case of deflation also happened. The resulting aftermath was so bad that economic policy since has been chiefly designed to prevent deflation at all costs.

Setting the Stage

The transition from wartime to peacetime created a bumpy economic road after World War I.

Growth has hard to come by in the first years after the war, and by 1920-21 the economy fell into a brief deflationary depression. Prices dropped -18%, and unemployment jumped up to 11.7% in 1921.

However, the troubles wouldn’t last. During the “Roaring Twenties”, economic growth picked up as the new technologies like the automobile, household appliances, and other mass-produced products led to a vibrant consumer culture and growth in the economy.

More than half of the automobiles in the nation were sold on credit by the end of the 1920s. Consumer debt more than doubled during the decade.

While GDP growth during this period was extremely strong, the Roaring Twenties also had a dark side. Income inequality during this era was the highest in American history. By 1929, the income of the top 1% had increased by 75%. Income for the rest of people (99%) increased by only 9%.

The Roaring Twenties ended with a bang. On Black Thursday (Oct 24, 1929), the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged 11% at the open in very heavy volume, precipitating the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s.

The Cause of the Great Depression

Economists continue to debate to this day on the cause of the Great Depression. Here’s perspectives from three different economic schools:

Keynesian:

John Maynard Keynes saw the causes of the Great Depression hinge upon a lack of aggregate demand. This later became the subject of his most influential work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, which was published in 1936.

Keynes argued that the solution was to stimulate the economy through some combination of two approaches:

1. A reduction in interest rates (monetary policy), and

2. Government investment in infrastructure (fiscal policy).

“The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.” – John Maynard Keynes

Monetarist:

Monetarists such as Milton Friedman viewed the cause of the Great Depression as a fall in the money supply.

Friedman and Schwartz argue that people wanted to hold more money than the Federal Reserve was supplying. As a result, people hoarded money by consuming less. This caused a contraction in employment and production since prices were not flexible enough to immediately fall.

“The Great Depression, like most other periods of severe unemployment, was produced by government mismanagement rather than by any inherent instability of the private economy.” ― Milton Friedman

Austrian:

Austrian economists argue that the Great Depression was the inevitable outcome of the monetary policies of the Federal Reserve during the 1920s.

In their opinion, the central bank’s policy was an “easy credit policy” which led to an unsustainable credit-driven boom.

“Any increase in the relative size of government in the economy, therefore, shifts the societal consumption-investment ratio in favor of consumption, and prolongs the depression.” – Murray Rothbard

The Great Depression and Deflation

Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide GDP fell by an estimated 15%.

Deflation hit.

Personal income, tax revenue, profits and prices plunged. International trade fell by more than 50%. Unemployment in the U.S. rose to 25% and in some countries rose as high as 33%.

These statistics were only the tip of the iceberg. Learn about the full effects, the stories, and the recovery from the Great Depression in Part 2.

About the Money Project

The Money Project aims to use intuitive visualizations to explore ideas around the very concept of money itself. Founded in 2015 by Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals, the Money Project will look at the evolving nature of money, and will try to answer the difficult questions that prevent us from truly understanding the role that money plays in finance, investments, and accumulating wealth.

Markets

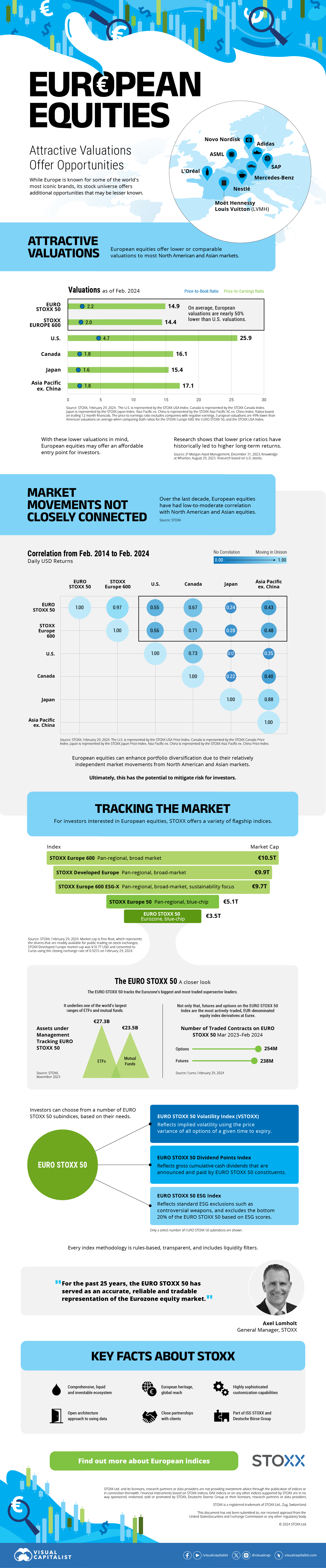

The European Stock Market: Attractive Valuations Offer Opportunities

On average, the European stock market has valuations that are nearly 50% lower than U.S. valuations. But how can you access the market?

European Stock Market: Attractive Valuations Offer Opportunities

Europe is known for some established brands, from L’Oréal to Louis Vuitton. However, the European stock market offers additional opportunities that may be lesser known.

The above infographic, sponsored by STOXX, outlines why investors may want to consider European stocks.

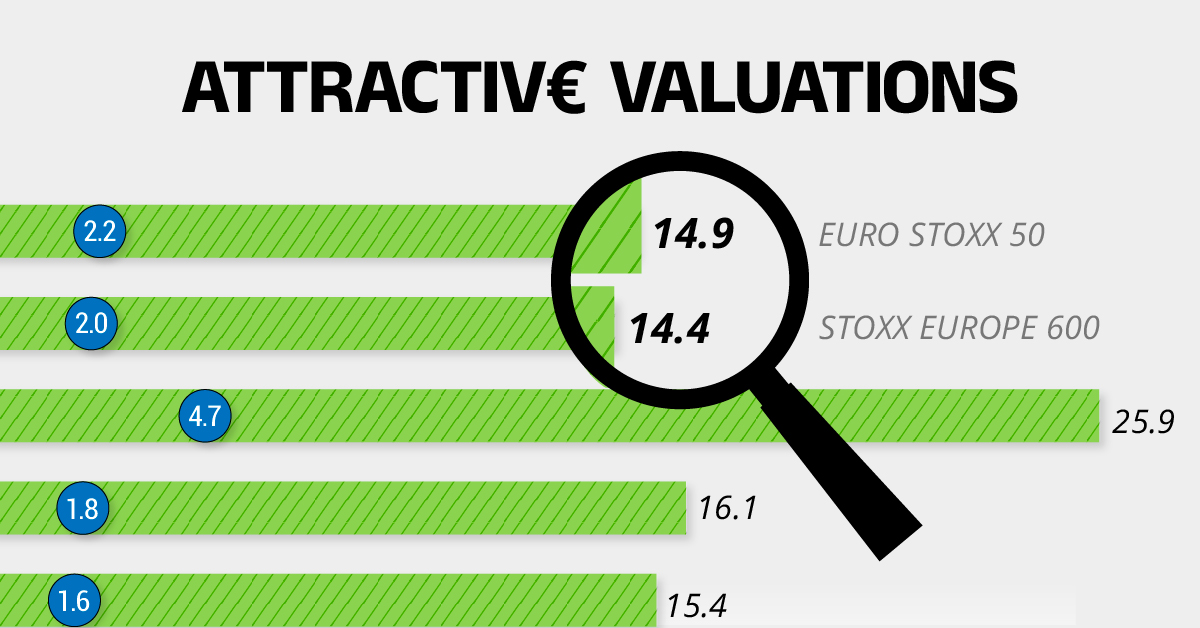

Attractive Valuations

Compared to most North American and Asian markets, European stocks offer lower or comparable valuations.

| Index | Price-to-Earnings Ratio | Price-to-Book Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| EURO STOXX 50 | 14.9 | 2.2 |

| STOXX Europe 600 | 14.4 | 2 |

| U.S. | 25.9 | 4.7 |

| Canada | 16.1 | 1.8 |

| Japan | 15.4 | 1.6 |

| Asia Pacific ex. China | 17.1 | 1.8 |

Data as of February 29, 2024. See graphic for full index names. Ratios based on trailing 12 month financials. The price to earnings ratio excludes companies with negative earnings.

On average, European valuations are nearly 50% lower than U.S. valuations, potentially offering an affordable entry point for investors.

Research also shows that lower price ratios have historically led to higher long-term returns.

Market Movements Not Closely Connected

Over the last decade, the European stock market had low-to-moderate correlation with North American and Asian equities.

The below chart shows correlations from February 2014 to February 2024. A value closer to zero indicates low correlation, while a value of one would indicate that two regions are moving in perfect unison.

| EURO STOXX 50 | STOXX EUROPE 600 | U.S. | Canada | Japan | Asia Pacific ex. China |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EURO STOXX 50 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| STOXX EUROPE 600 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.48 | |

| U.S. | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ||

| Canada | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.40 | |||

| Japan | 1.00 | 0.88 | ||||

| Asia Pacific ex. China | 1.00 |

Data is based on daily USD returns.

European equities had relatively independent market movements from North American and Asian markets. One contributing factor could be the differing sector weights in each market. For instance, technology makes up a quarter of the U.S. market, but health care and industrials dominate the broader European market.

Ultimately, European equities can enhance portfolio diversification and have the potential to mitigate risk for investors.

Tracking the Market

For investors interested in European equities, STOXX offers a variety of flagship indices:

| Index | Description | Market Cap |

|---|---|---|

| STOXX Europe 600 | Pan-regional, broad market | €10.5T |

| STOXX Developed Europe | Pan-regional, broad-market | €9.9T |

| STOXX Europe 600 ESG-X | Pan-regional, broad market, sustainability focus | €9.7T |

| STOXX Europe 50 | Pan-regional, blue-chip | €5.1T |

| EURO STOXX 50 | Eurozone, blue-chip | €3.5T |

Data is as of February 29, 2024. Market cap is free float, which represents the shares that are readily available for public trading on stock exchanges.

The EURO STOXX 50 tracks the Eurozone’s biggest and most traded companies. It also underlies one of the world’s largest ranges of ETFs and mutual funds. As of November 2023, there were €27.3 billion in ETFs and €23.5B in mutual fund assets under management tracking the index.

“For the past 25 years, the EURO STOXX 50 has served as an accurate, reliable and tradable representation of the Eurozone equity market.”

— Axel Lomholt, General Manager at STOXX

Partnering with STOXX to Track the European Stock Market

Are you interested in European equities? STOXX can be a valuable partner:

- Comprehensive, liquid and investable ecosystem

- European heritage, global reach

- Highly sophisticated customization capabilities

- Open architecture approach to using data

- Close partnerships with clients

- Part of ISS STOXX and Deutsche Börse Group

With a full suite of indices, STOXX can help you benchmark against the European stock market.

Learn how STOXX’s European indices offer liquid and effective market access.

-

Economy1 day ago

Economy1 day agoEconomic Growth Forecasts for G7 and BRICS Countries in 2024

The IMF has released its economic growth forecasts for 2024. How do the G7 and BRICS countries compare?

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoU.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

U.S. debt interest payments have surged past the $1 trillion dollar mark, amid high interest rates and an ever-expanding debt burden.

-

United States1 week ago

United States1 week agoRanked: The Largest U.S. Corporations by Number of Employees

We visualized the top U.S. companies by employees, revealing the massive scale of retailers like Walmart, Target, and Home Depot.

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

This graphic shows the states with the highest real GDP growth rate in 2023, largely propelled by the oil and gas boom.

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

In this graphic, we show the highest earning flight routes globally as air travel continued to rebound in 2023.

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

The U.S. residential real estate market is worth a staggering $47.5 trillion. Here are the most valuable housing markets in the country.

-

Mining1 week ago

Mining1 week agoGold vs. S&P 500: Which Has Grown More Over Five Years?

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries