Money

Life and Times During the Great Depression

Life and Times During the Great Depression

The Money Project is an ongoing collaboration between Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals that seeks to use intuitive visualizations to explore the origins, nature, and use of money.

The economy of the United States was destroyed almost overnight.

More than 5,000 banks collapsed, and there were 12 million people out of work in America as factories, banks, and other shops closed.

Many reasons have been supplied by the different economic camps for the cause of the Great Depression, which we reviewed in the first part of this series.

Regardless of the causes, the combination of deflationary pressures and a collapsing economy created one of the most desperate and miserable eras of American history. The resulting aftermath was so bad, that almost every future Central Bank policy would be designed primarily to combat such deflation.

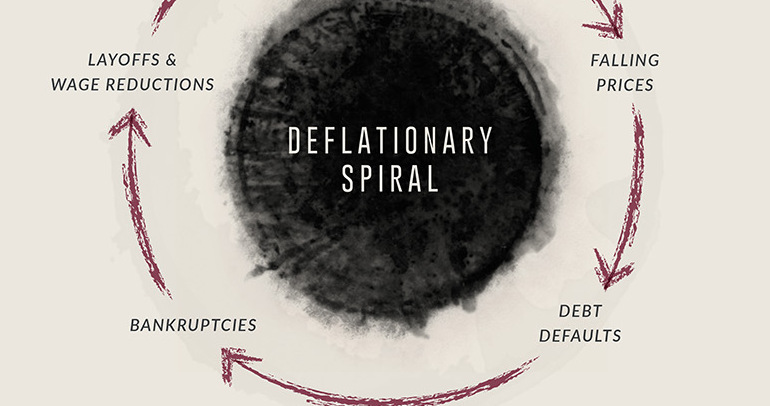

The Deflationary Spiral

After the stock crash, money and consumer confidence was hard to find. Instead of spending money on new things, people hoarded their cash.

Fewer dollars spent meant more drops in demand and prices, which led to defaults, bankruptcies, and layoffs.

As a result of this spiral, the prices for many food items in the U.S. fell by nearly 50% from their pre-WW1 levels.

The price of butter went from pre-crisis levels of $0.21 to $0.13 per pound in 1932. Wool had a drop from $0.24 to $0.10 per pound, and most other goods followed the same price trajectory.

The Effects

Here’s how “real value” is affected in a deflationary environment:

Money

Real value increases: cash is king and gains in real value.

Assets (stocks, real estate)

Real value decreases as prices fall.

Debt

Debtors owe more in real terms

Interest Rates

Real interest rates (nominal rates minus inflation) can rise as inflation is negative, causing unwanted tightening.

From Bad to Worse

The Great Depression lasted from 1929 to 1939, which was unprecedented in length for modern history.

To this day, economists disagree on why the Depression lasted so long. Here’s some of their explanations:

The New Deal was not enough

Looking back on The Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes believed that monetary policy could only go so far.

The Central Bank could not ultimately push banks to lend, and therefore demand had to be created through fiscal policy. Keynes advocated massive deficit spending to offset markets’ failure to recover.

Keynesians such as Paul Krugman believe that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s economic policies through The New Deal were too cautious.

“You can’t push on a string.” – Keynes

The New Deal made things worse

Some economists believe the New Deal had a negative net effect on the recovery.

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) is a primary subject of this criticism. Established in 1933, the goal of the NRA was to lift wages. To do this, it got industry leaders to meet and establish minimum prices and wages for workers.

Cole and Ohanian claim that this essentially created cartels that destroyed economic competition. They calculate that this, along with the aftermath of these policies, accounted for 60% of the weak recovery.

Lastly, one other charge leveled at Roosevelt by his critics is that the sprawling policies from the New Deal ultimately created uncertainty for business leaders, leading to less investment. This lengthened the recovery.

“[The] abandonment of [Roosevelt’s] policies coincided with the strong economic recovery of the 1940s.” – Cole and Ohanian

The Federal Reserve didn’t do enough

Milton Friedman claimed that the Federal Reserve made the wrong policy decision, which extended the length of the Depression.

Between 1929 and 1933, the monetary supply dipped 27%, which decreased aggregate demand and then prices. The Fed’s failure was in not realizing what was happening and not taking corrective action.

“The contraction is…a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces…[D]ifferent and feasible actions by the monetary authorities could have prevented the decline in the stock of money… [This] would have reduced the contraction’s severity and almost as certainly its duration.” – Milton Friedman (and co-author Anna Schwartz)

The Federal Reserve shouldn’t have done anything

Austrian economists believe that the Fed and government both made policy choices that slowed the recovery.

For starters, most agree with Friedman that the Fed’s policy choices at the start of the Depression led to deflation.

They also point to the premature tightening that occurred in 1936 and 1937 as a policy failure. During those two years, the Fed not only hiked interest rates, but it also doubled bank-reserve requirements. These policies coincided with Roosevelt’s tax hikes, and a recession occurred within the Depression from 1937 to 1938.

Critics of these policies say that this delayed the recovery by years.

“I agree with Milton Friedman that once the Crash had occurred, the Federal Reserve System pursued a silly deflationary policy. I am not only against inflation but I am also against deflation. So, once again, a badly programmed monetary policy prolonged the depression.” – Friedrich Hayek

Personal Stories from The Great Depression

“One evening when we went down to check on the bank, there were hundreds of people out front yelling and crying and fighting and beating on the locked doors and windows. They had fires built in the street to keep warm and there were people milling around all over the downtown.” – Vane Scott, Ohio

“A friend I worked with said in the Depression he rode the rails and stopped to eat vegetables out of a garden. The owner said he would shoot him if he didn’t stop. My friend said ‘go ahead,’ as he was that hungry. ” – James Randolph, Ohio

“When neighbors couldn’t get a loan from the bank, they’d come to Dad. He sold farm machinery. He never put his money in a bank. He stored it in a strongbox in the fruit cellar, under the apples. He’d loan the neighbors what they needed and they paid him back when they could. If there was a month—especially the winter months—when they couldn’t pay, they’d slaughter a cow or a pig and give him a portion. In the summer it was vegetables: corn, peas, whatever they had growing.” – Gladys Hoffman, New York

“I thought the Depression was going to go on forever. For six or seven years, it didn’t look as though things were getting better. The people in Washington DC said they were, but ask the man on the road? He was hungry and his clothes were ragged and he didn’t have a job. He didn’t think things were picking up.” – Arvel “Sunshine” Pearson, Arkansas

Conclusion

After the 1937-38 Recession, the United States economy began to recover.

The focus of the American public would eventually shift away from the Great Depression, as events in Europe unfolded after Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

About the Money Project

The Money Project aims to use intuitive visualizations to explore ideas around the very concept of money itself. Founded in 2015 by Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals, the Money Project will look at the evolving nature of money, and will try to answer the difficult questions that prevent us from truly understanding the role that money plays in finance, investments, and accumulating wealth.

Money

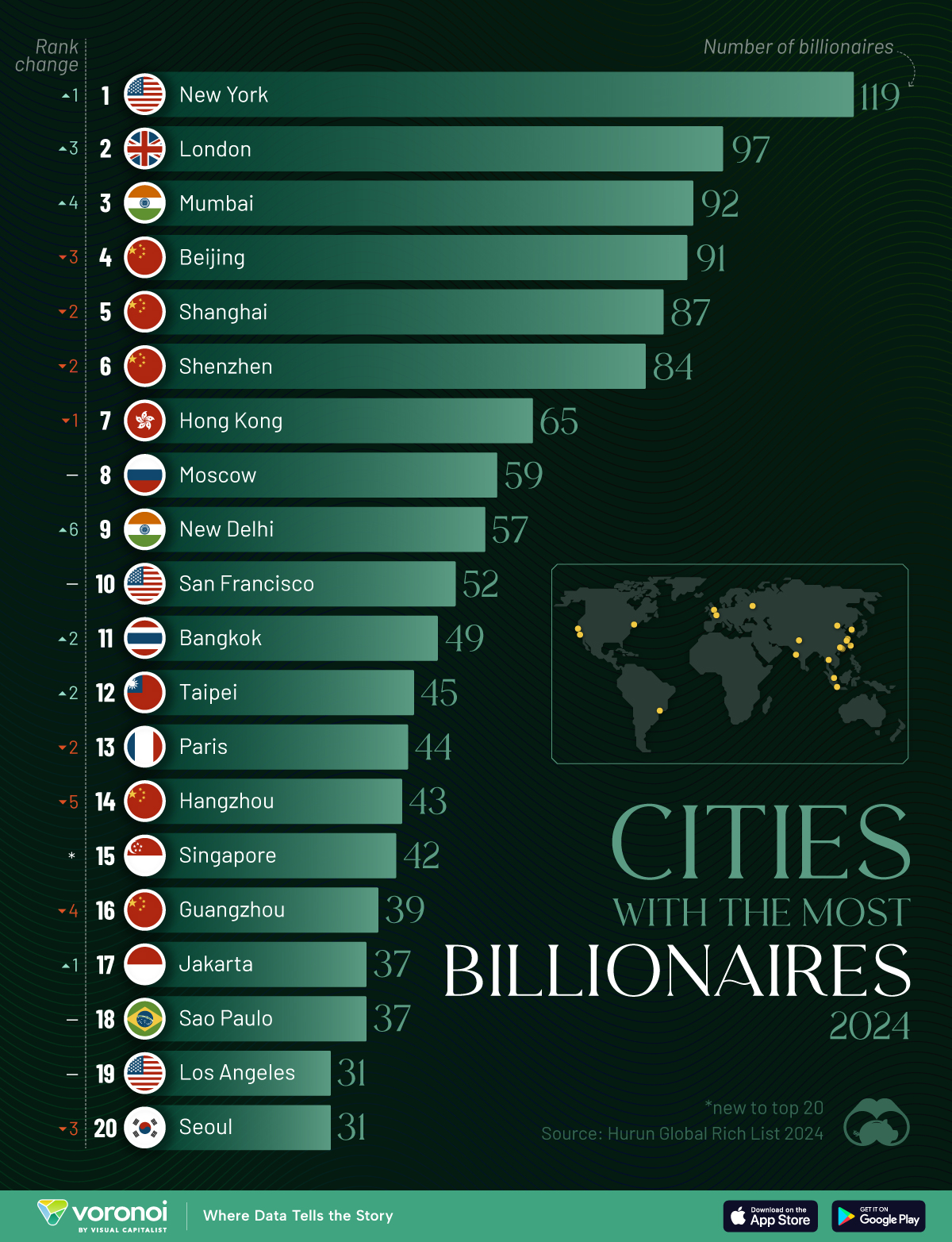

Charted: Which City Has the Most Billionaires in 2024?

Just two countries account for half of the top 20 cities with the most billionaires. And the majority of the other half are found in Asia.

Charted: Which Country Has the Most Billionaires in 2024?

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Some cities seem to attract the rich. Take New York City for example, which has 340,000 high-net-worth residents with investable assets of more than $1 million.

But there’s a vast difference between being a millionaire and a billionaire. So where do the richest of them all live?

Using data from the Hurun Global Rich List 2024, we rank the top 20 cities with the highest number of billionaires in 2024.

A caveat to these rich lists: sources often vary on figures and exact rankings. For example, in last year’s reports, Forbes had New York as the city with the most billionaires, while the Hurun Global Rich List placed Beijing at the top spot.

Ranked: Top 20 Cities with the Most Billionaires in 2024

The Chinese economy’s doldrums over the course of the past year have affected its ultra-wealthy residents in key cities.

Beijing, the city with the most billionaires in 2023, has not only ceded its spot to New York, but has dropped to #4, overtaken by London and Mumbai.

| Rank | City | Billionaires | Rank Change YoY |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 🇺🇸 New York | 119 | +1 |

| 2 | 🇬🇧 London | 97 | +3 |

| 3 | 🇮🇳 Mumbai | 92 | +4 |

| 4 | 🇨🇳 Beijing | 91 | -3 |

| 5 | 🇨🇳 Shanghai | 87 | -2 |

| 6 | 🇨🇳 Shenzhen | 84 | -2 |

| 7 | 🇭🇰 Hong Kong | 65 | -1 |

| 8 | 🇷🇺 Moscow | 59 | No Change |

| 9 | 🇮🇳 New Delhi | 57 | +6 |

| 10 | 🇺🇸 San Francisco | 52 | No Change |

| 11 | 🇹🇭 Bangkok | 49 | +2 |

| 12 | 🇹🇼 Taipei | 45 | +2 |

| 13 | 🇫🇷 Paris | 44 | -2 |

| 14 | 🇨🇳 Hangzhou | 43 | -5 |

| 15 | 🇸🇬 Singapore | 42 | New to Top 20 |

| 16 | 🇨🇳 Guangzhou | 39 | -4 |

| 17T | 🇮🇩 Jakarta | 37 | +1 |

| 17T | 🇧🇷 Sao Paulo | 37 | No Change |

| 19T | 🇺🇸 Los Angeles | 31 | No Change |

| 19T | 🇰🇷 Seoul | 31 | -3 |

In fact all Chinese cities on the top 20 list have lost billionaires between 2023–24. Consequently, they’ve all lost ranking spots as well, with Hangzhou seeing the biggest slide (-5) in the top 20.

Where China lost, all other Asian cities—except Seoul—in the top 20 have gained ranks. Indian cities lead the way, with New Delhi (+6) and Mumbai (+3) having climbed the most.

At a country level, China and the U.S combine to make up half of the cities in the top 20. They are also home to about half of the world’s 3,200 billionaire population.

In other news of note: Hurun officially counts Taylor Swift as a billionaire, estimating her net worth at $1.2 billion.

-

Mining1 week ago

Mining1 week agoGold vs. S&P 500: Which Has Grown More Over Five Years?

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Countries2 weeks ago

Countries2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries