Misc

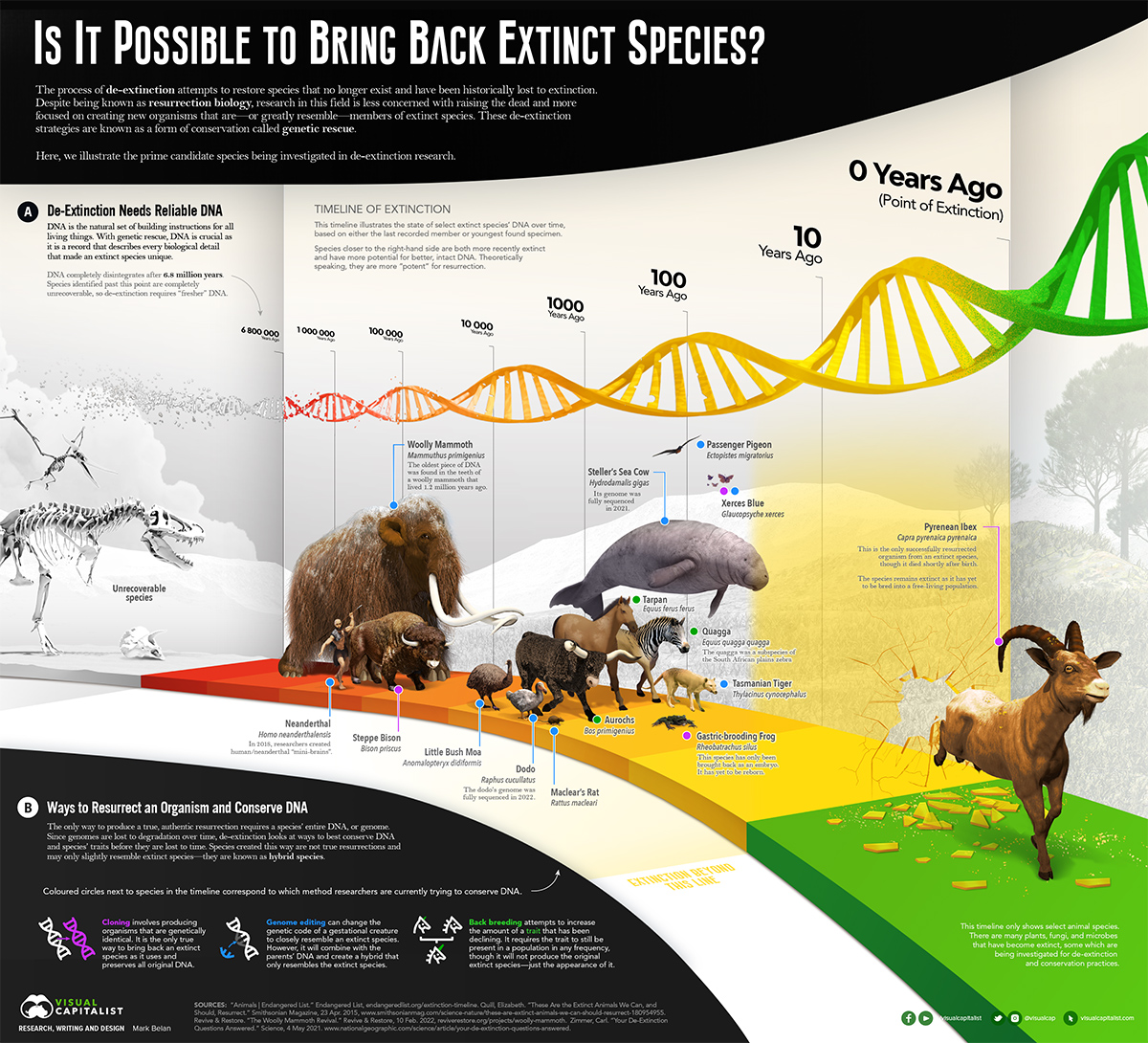

Is it Possible to Bring Back Extinct Animal Species?

View a higher resolution version of this infographic.

Is it Possible to Bring Back Extinct Animal Species?

View a higher resolution version of this infographic.

Humanity has been tinkering with natural life for thousands of years.

We’ve become remarkably good at it, too—to date, we’ve modified bacteria to produce drugs, created crops with built-in pesticides, and even made a glow-in-the-dark dog.

However, despite our many achievements in the realm of genetic engineering, one thing we’re still working on is bringing extinct animals back to life.

But scientists are working on it. In fact, there’s a whole field of biology that’s focused on reviving extinct species.

This graphic provides a brief introduction to the fascinating field of science known as resurrection biology—or de-extinction.

The Benefits of De-Extinction

First thing’s first—what is the point of bringing back extinct animals?

There are a number of research benefits that come with de-extinction. For instance, some scientists believe studying previously extinct animals and looking at how they function could help fill some gaps in our current theories around evolution.

De-extinction could also have a beneficial impact on the environment. That’s because when an animal goes extinct, its absence has a ripple effect on all the flora and fauna involved in that animal’s food web.

Because of this, reintroducing previously extinct species back into their old ecosystems could help rebalance and restore off-kilter environments.

There’s even a possibility that de-extinction could slow down global warming. Scientist Sergey Zimov believes that, if we were to reintroduce an animal that’s similar to the woolly mammoth back to the tundra, it could help repopulate the area, regrow ancient plains, and possibly slow the melting of the ice caps.

How Does it Work?

The key element that’s needed to re-create a species is its DNA.

Unfortunately, DNA slowly degrades, and once it’s gone completely, there’s no way to recover it. Researchers believe DNA has a half-life of 521 years, so after 6.8 million years, it’s believed to be completely gone.

That’s why species like dinosaurs have virtually no chance of de-extinction. However, many organisms that went extinct more recently, like the dodo, could have a chance of conservation.

When it comes to de-extinction, there are three main techniques:

① Cloning

This is the only way to create an exact DNA replica of something.

However, a complete genome is needed for this, so this form of genetic rescue is most effective with recently-lost species, or species that are nearing extinction.

② Genome Editing

Genome editing is the manipulation of DNA to mimic extinct DNA.

There are several ways to do this, but in general, the process involves researchers manipulating the genomes of living species to make a new species that closely resembles an extinct one.

Because it’s not an exact copy of the extinct species’ DNA, this method will create a hybrid species that only resembles the extinct animal.

③ Back-Breeding

A form of breeding where a distinguishing trait from an extinct species (a horn or a color pattern) is bred back into living populations.

This requires the trait to still exist in some frequency in similar species, and the trait is selectively bred back into popularity.

Like genome editing, this method does not resurrect an extinct species, but resurrects the DNA and genetic diversity that gave the extinct species a distinguishing trait.

Is Bringing Back Extinct Animal Species Really Worth it?

While there’s a ton of buzz and potential around the idea of bringing back extinct animal species, there are a few critics that believe our efforts would be better spent on other things.

Research on the economics of de-extinction found that the money would go farther if it was invested into conservation programs for living species—approximately two to eight times more species could be saved if invested in existing conversation programs.

In an article in Science, Joseph Bennett, a biologist at Carleton University in Ottawa, said “if [a] billionaire is only interested in bringing back a species from the dead, power to him or her.”

Bennett added, “however, if that billionaire is couching it in terms of it being a biodiversity conservation, then that’s disingenuous. There are plenty of species out there on the verge of extinction now that could be saved with the same resources.”

VC+

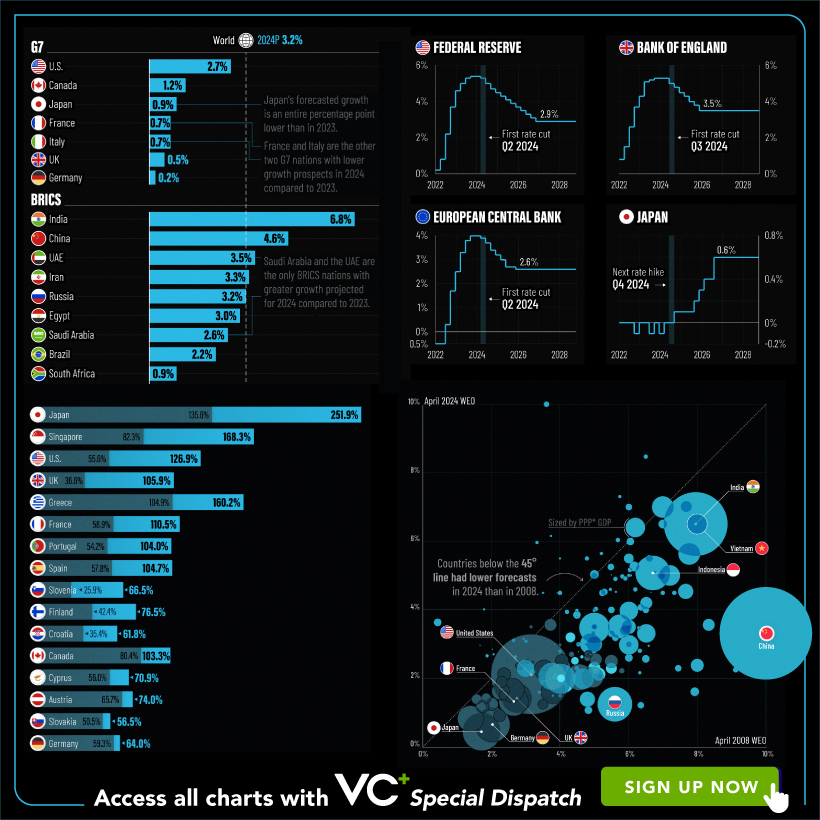

VC+: Get Our Key Takeaways From the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

A sneak preview of the exclusive VC+ Special Dispatch—your shortcut to understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook report.

Have you read IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook yet? At a daunting 202 pages, we don’t blame you if it’s still on your to-do list.

But don’t worry, you don’t need to read the whole April release, because we’ve already done the hard work for you.

To save you time and effort, the Visual Capitalist team has compiled a visual analysis of everything you need to know from the report—and our VC+ Special Dispatch is available exclusively to VC+ members. All you need to do is log into the VC+ Archive.

If you’re not already subscribed to VC+, make sure you sign up now to access the full analysis of the IMF report, and more (we release similar deep dives every week).

For now, here’s what VC+ members get to see.

Your Shortcut to Understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook

With long and short-term growth prospects declining for many countries around the world, this Special Dispatch offers a visual analysis of the key figures and takeaways from the IMF’s report including:

- The global decline in economic growth forecasts

- Real GDP growth and inflation forecasts for major nations in 2024

- When interest rate cuts will happen and interest rate forecasts

- How debt-to-GDP ratios have changed since 2000

- And much more!

Get the Full Breakdown in the Next VC+ Special Dispatch

VC+ members can access the full Special Dispatch by logging into the VC+ Archive, where you can also check out previous releases.

Make sure you join VC+ now to see exclusive charts and the full analysis of key takeaways from IMF’s World Economic Outlook.

Don’t miss out. Become a VC+ member today.

What You Get When You Become a VC+ Member

VC+ is Visual Capitalist’s premium subscription. As a member, you’ll get the following:

- Special Dispatches: Deep dive visual briefings on crucial reports and global trends

- Markets This Month: A snappy summary of the state of the markets and what to look out for

- The Trendline: Weekly curation of the best visualizations from across the globe

- Global Forecast Series: Our flagship annual report that covers everything you need to know related to the economy, markets, geopolitics, and the latest tech trends

- VC+ Archive: Hundreds of previously released VC+ briefings and reports that you’ve been missing out on, all in one dedicated hub

You can get all of the above, and more, by joining VC+ today.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoHow Hard Is It to Get Into an Ivy League School?

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoWhere U.S. Inflation Hit the Hardest in March 2024

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoTop Countries By Forest Growth Since 2001