Misc

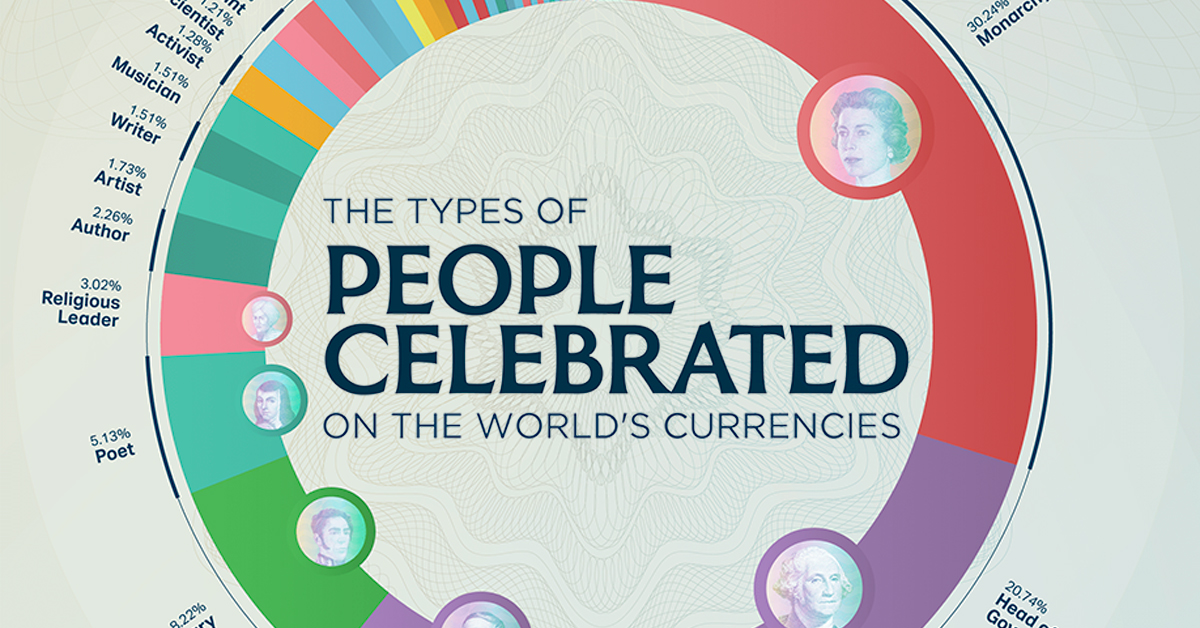

What Types of People Appear Most on International Currencies?

What Types of People Appear Most on International Currencies?

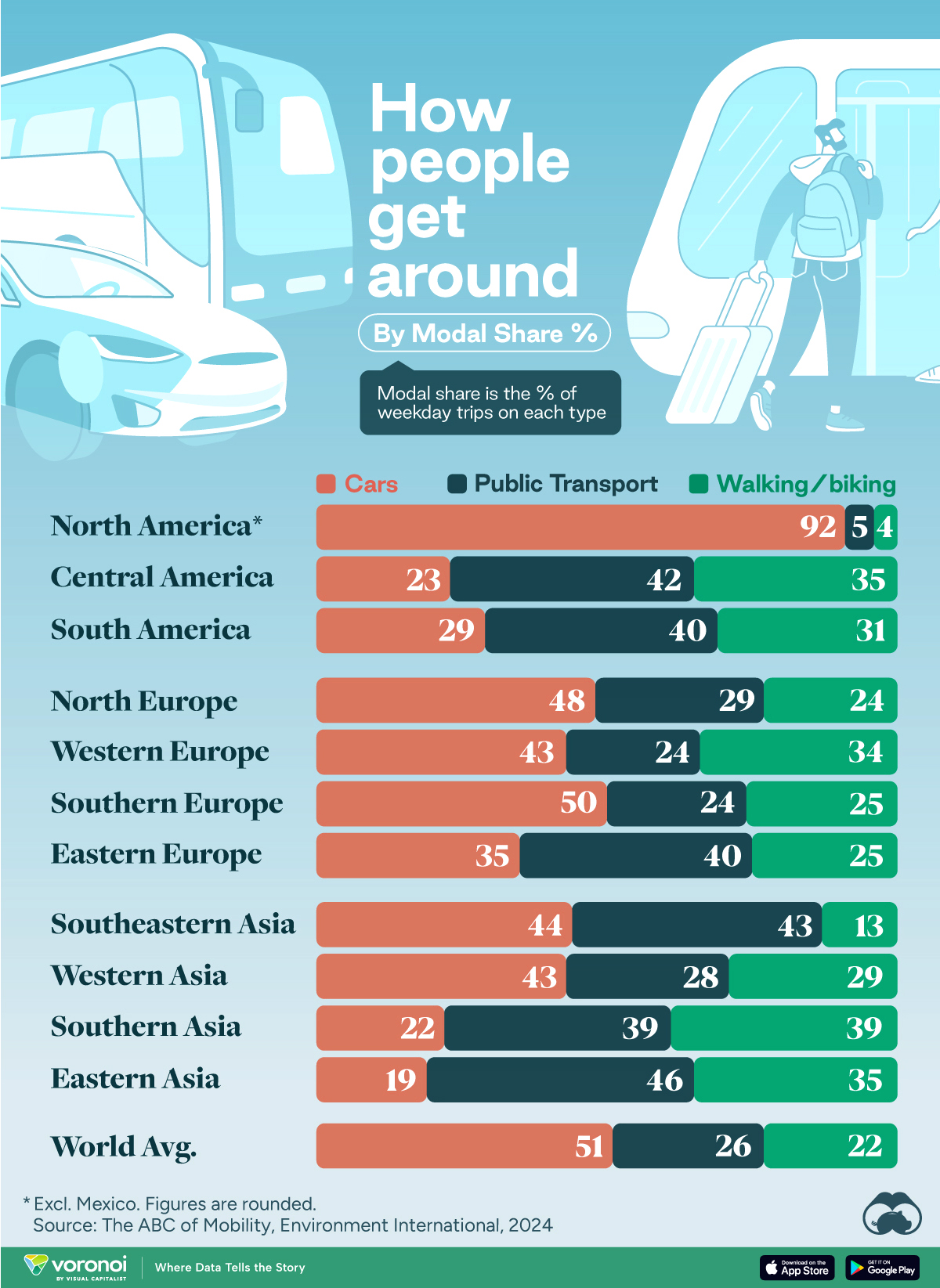

On currencies throughout the world, you’ll see everything from revolutionaries to poets featured prominently. But how does this mix of notable people break down quantitatively?

This graphic by NetCredit shows the types of people, by their main occupations and roles, that are featured on banknotes and coins worldwide.

Global Money Features Power

To find out the types of people most featured on money, NetCredit analyzed all the banknotes and coins in circulation in every country across the globe in 2022.

From monarchs to athletes, the analysis found that many types of people appear on banknotes and coins worldwide. In fact, 51 different main occupations and roles were identified, which were then organized into eight overarching categories:

- Leadership

- Government

- Society

- Sport & Recreation

- Military & Espionage

- Religion

- The Arts

- Humanity

Here’s a breakdown of all 51 different occupations, and what percentage of worldwide currencies they’re featured on:

| Occupation | Category | % on Currencies |

|---|---|---|

| Monarch | Leadership | 30.24% |

| Head of government | Government | 20.74% |

| Politician | Government | 10.03% |

| Military | Military & Esionage | 8.22% |

| Poet | The Arts | 5.13% |

| Religious leader | Religion | 3.02% |

| Author | The Arts | 2.26% |

| Artist | The Arts | 1.73% |

| Writer | The Arts | 1.51% |

| Musician | The Arts | 1.51% |

| Activist | Society | 1.28% |

| Scientist | Science & Humanities | 1.21% |

| Movement leader | Leadership | 0.98% |

| Saint | Religion | 0.98% |

| Explorer | Science & Humanities | 0.90% |

| Inventor | Science & Humanities | 0.83% |

| Scholar | Science & Humanities | 0.83% |

| Revolutionary | Leadership | 0.60% |

| Business | Society | 0.60% |

| Hero | Society | 0.60% |

| Athlete | Sport & Recreation | 0.60% |

| Supreme leader | Leadership | 0.53% |

| Educator | Science & Humanities | 0.53% |

| Historian | Science & Humanities | 0.45% |

| Singer | The Arts | 0.45% |

| Nationalist leader | Leadership | 0.38% |

| Doctor | Science & Humanities | 0.38% |

| Mathematician | Science & Humanities | 0.38% |

| Chief | Leadership | 0.30% |

| Architect | Science & Humanities | 0.30% |

| Economist | Science & Humanities | 0.30% |

| Philosopher | Science & Humanities | 0.23% |

| Actor | The Arts | 0.23% |

| Chief of state | Government | 0.15% |

| Revolutionary leader | Leadership | 0.15% |

| Intellectual | Science & Humanities | 0.15% |

| Lawyer | Science & Humanities | 0.15% |

| Wife | Society | 0.15% |

| Spy | Military & Esionage | 0.08% |

| Rector | Religion | 0.08% |

| Civil engineer | Science & Humanities | 0.08% |

| Linguist | Science & Humanities | 0.08% |

| Philanthropist | Science & Humanities | 0.08% |

| Anthropologist | Science and Humanities | 0.08% |

| Social worker | Society | 0.08% |

| Ballerina | Sport & Recreation | 0.08% |

| Chess champion | Sport & Recreation | 0.08% |

| Mountaineer | Sport & Recreation | 0.08% |

| Actress | The Arts | 0.08% |

| Film director | The Arts | 0.08% |

The analysis shows that over 50% of the people featured on money are either monarchs or heads of government, many of which are no longer in power.

For instance, Belize was once a British colony and still features the late Elizabeth II on all of its currency—even though the country gained independence from the UK in 1981.

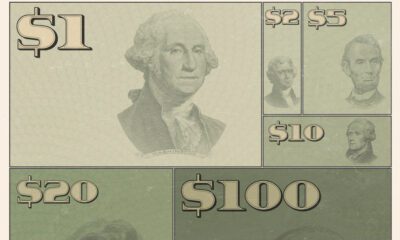

And everyone featured on U.S. currency is also a historical figure. Putting living celebrities on U.S. money has been banned since 1866, after Spencer Clark, who was the Superintendent of the U.S. National Currency Bureau at the time, printed his own face on the 5-cent banknote instead of the explorer William Clark of “Lewis and Clark.”

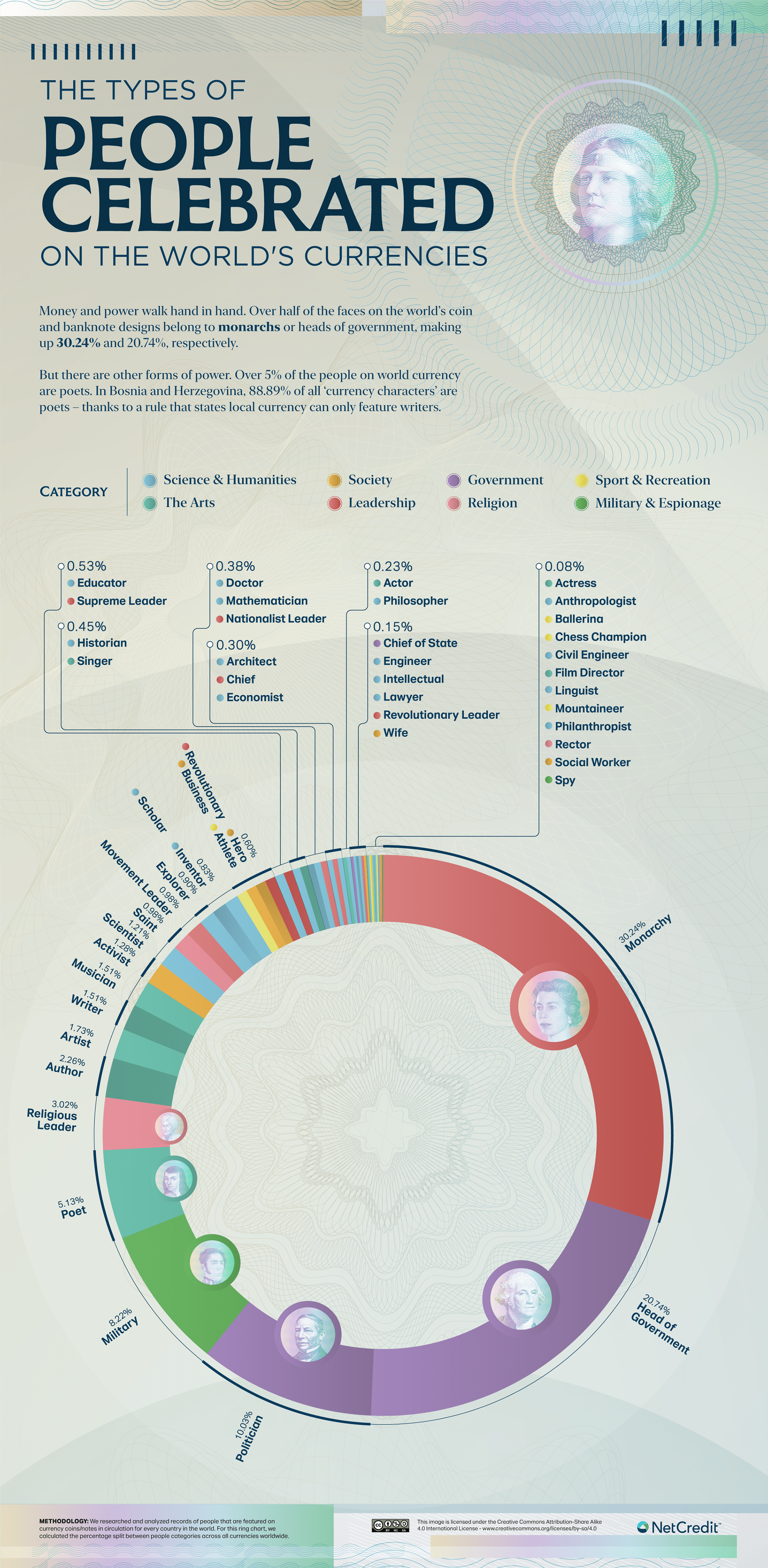

International Currencies: The Most Popular Figure Heads

Featured on over 100 different currencies around the world, the late Elizabeth II is the most featured person on banknotes and coins.

This makes sense considering the UK’s widespread historical reach. During the height of its reign in the early 20th century, the British Empire ruled nearly a quarter of the world.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, 6 of the top 10 most-featured people on currencies are monarchs, while the rest are heads of government.

Women on Banknotes

While Elizabeth II is the most featured person on currencies around the world, it’s worth mentioning that few other women have been given the same honor.

A study analyzed 1,006 current international banknotes and found that only 15% featured images of women.

However, some countries are actively trying to celebrate more women on their money. For example, the U.S. has been planning to put Harriet Tubman on the U.S. $20 bill for years, and while there have been some delays, the bill is currently on track to get released by 2030.

This article was published as a part of Visual Capitalist's Creator Program, which features data-driven visuals from some of our favorite Creators around the world.

Automotive

How People Get Around in America, Europe, and Asia

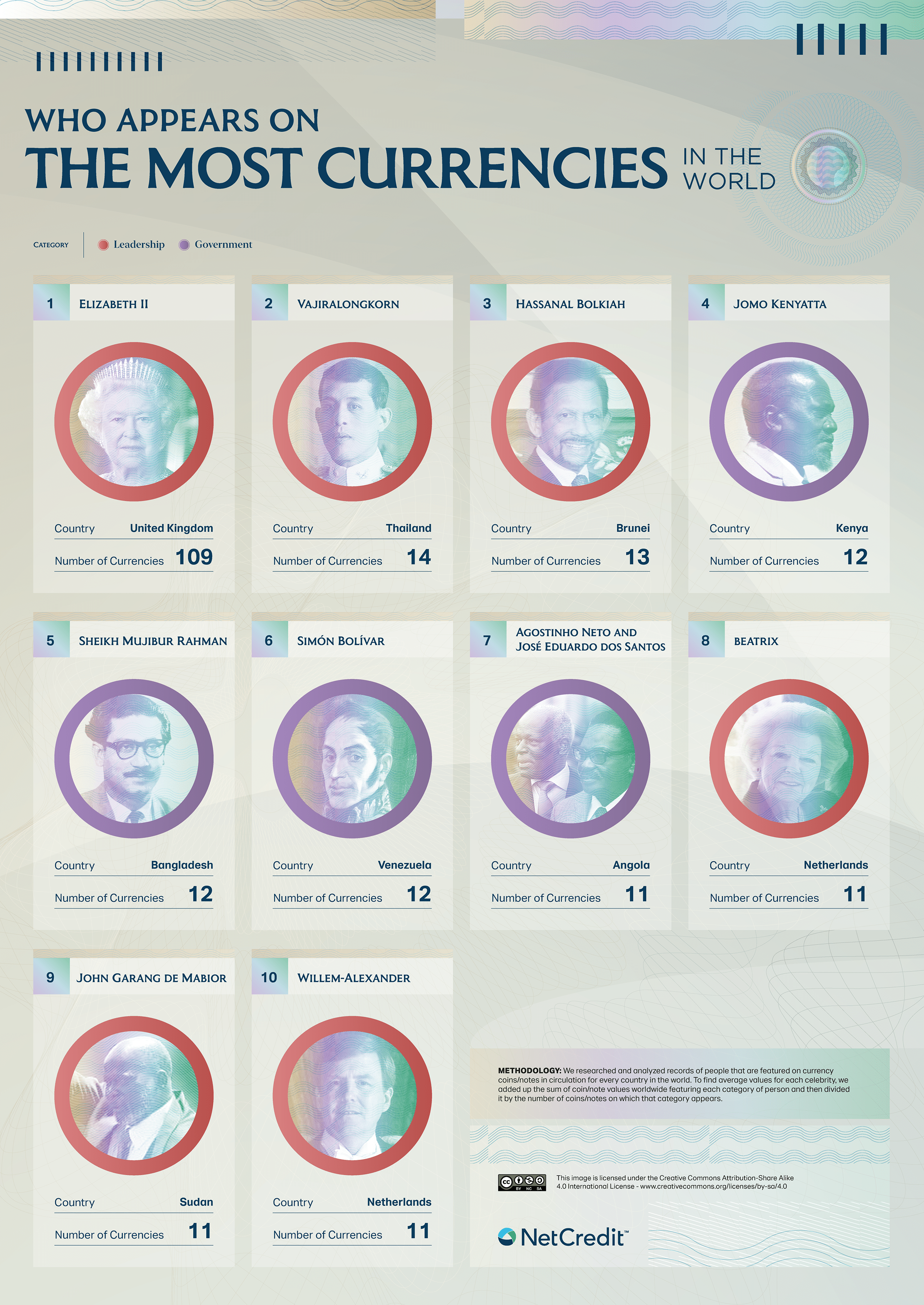

Examining how people get around using cars, public transit, and walking or biking, and the regional differences in usage.

How People Get Around in America, Europe, and Asia

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

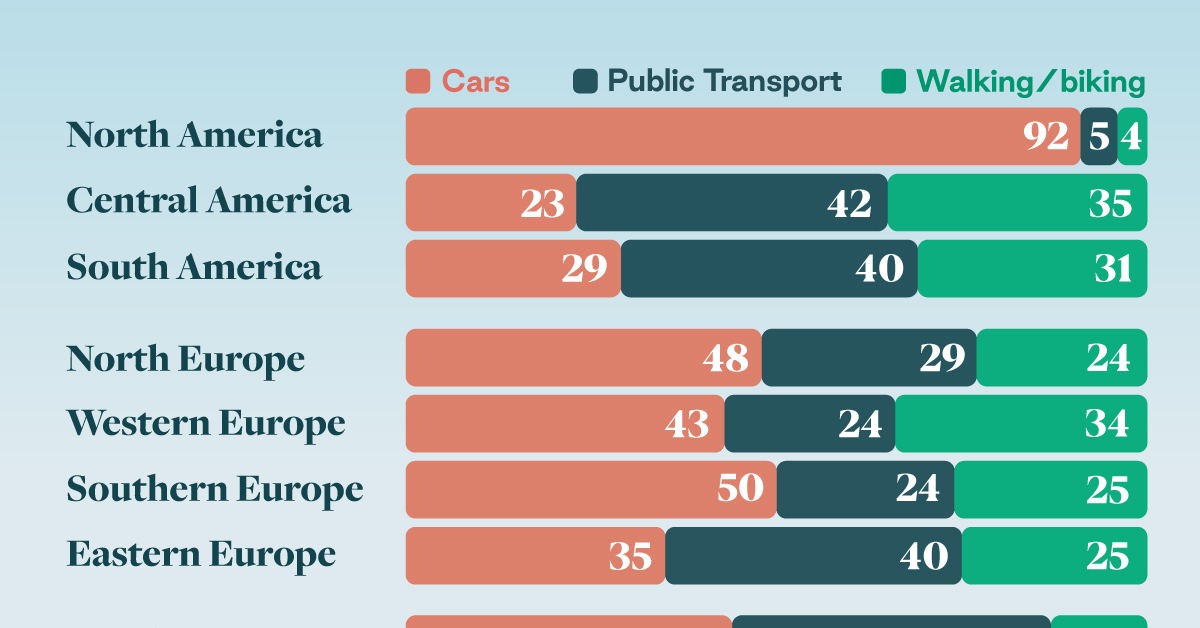

This chart highlights the popularity of different transportation types in the Americas, Europe, and Asia, calculated by modal share.

Data for this article and visualization is sourced from ‘The ABC of Mobility’, a research paper by Rafael Prieto-Curiel (Complexity Science Hub) and Juan P. Ospina (EAFIT University), accessed through ScienceDirect.

The authors gathered their modal share data through travel surveys, which focused on the primary mode of transportation a person employs for each weekday trip. Information from 800 cities across 61 countries was collected for this study.

North American Car Culture Contrasts with the Rest of the World

In the U.S. and Canada, people heavily rely on cars to get around, no matter the size of the city. There are a few exceptions of course, such as New York, Toronto, and smaller college towns across the United States.

| Region | 🚗 Cars | 🚌 Public Transport | 🚶 Walking/Biking |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America* | 92% | 5% | 4% |

| Central America | 23% | 42% | 35% |

| South America | 29% | 40% | 31% |

| Northern Europe | 48% | 29% | 24% |

| Western Europe | 43% | 24% | 34% |

| Southern Europe | 50% | 24% | 25% |

| Eastern Europe | 35% | 40% | 25% |

| Southeastern Asia | 44% | 43% | 13% |

| Western Asia | 43% | 28% | 29% |

| Southern Asia | 22% | 39% | 39% |

| Eastern Asia | 19% | 46% | 35% |

| World | 51% | 26% | 22% |

Note: *Excluding Mexico. Percentages are rounded.

As a result, North America’s share of public transport and active mobility (walking and biking) is the lowest amongst all surveyed regions by a significant amount.

On the other hand, public transport reigns supreme in South and Central America as well as Southern and Eastern Asia. It ties with cars in Southeastern Asia, and is eclipsed by cars in Western Asia.

As outlined in the paper, Europe sees more city-level differences in transport popularity.

For example, Utrecht, Netherlands prefers walking and biking. People in Paris and London like using their extensive transit systems. And in Manchester and Rome, roughly two out of three journeys are by car.

-

Markets5 days ago

Markets5 days agoVisualizing Global Inflation Forecasts (2024-2026)

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoThe Carbon Footprint of Major Travel Methods

-

United States2 weeks ago

United States2 weeks agoVisualizing the Most Common Pets in the U.S.

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoThe World’s Top Media Franchises by All-Time Revenue

-

voronoi1 week ago

voronoi1 week agoBest Visualizations of April on the Voronoi App

-

Wealth1 week ago

Wealth1 week agoCharted: Which Country Has the Most Billionaires in 2024?

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Top Private Equity Firms by Country

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoThe Best U.S. Companies to Work for According to LinkedIn