Technology

Saying Bye to Facebook: Why Companies Change Their Name

As anyone who’s started a company knows, choosing a name is no easy task.

There are many considerations, such as:

- Are the social handles and domain name available?

- Is there a competitor already using a similar name?

- Can people spell, pronounce, and remember the name?

- Are there cultural or symbolic interpretations that could be problematic?

The list goes on. These considerations are amplified when a company is already established, and even more difficult when your company serves billions of users around the globe.

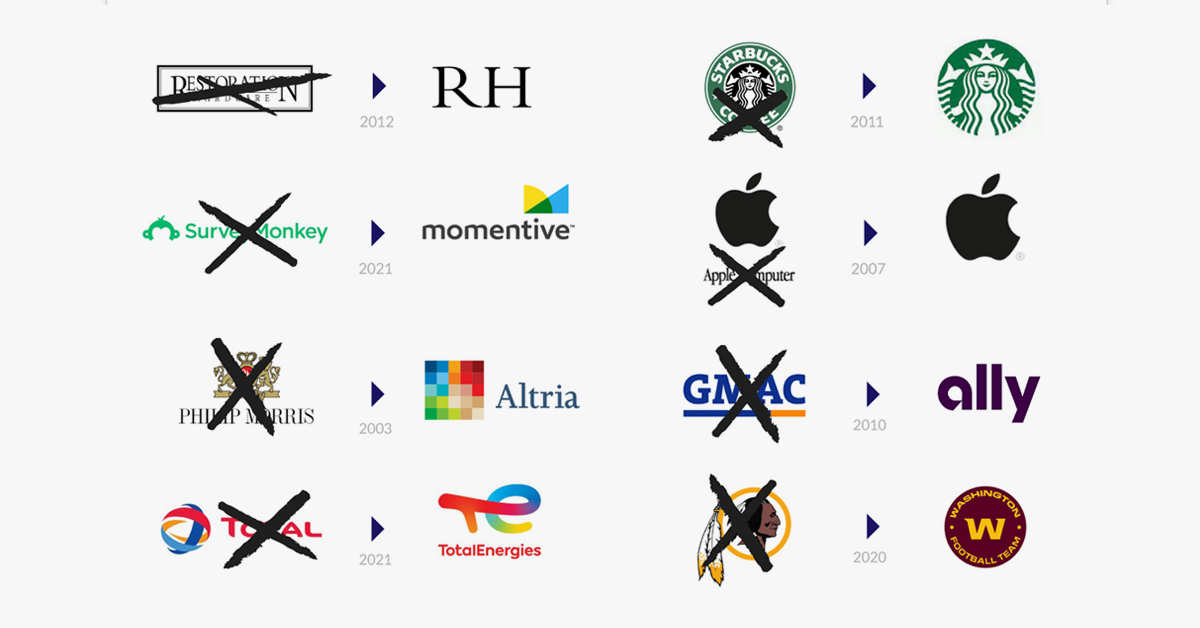

Facebook (the parent company, not the social network) has changed its name to Meta, and we’ll examine some probable reasons for the rebrand. But first we’ll look at historical corporate name changes in recent history, exploring the various motivations behind why a company might change its name. Below are some of the categories of rebranding that stand out the most.

Social Pressure

Societal perceptions can change fast, and companies do their best to anticipate these changes in advance. Or, if they don’t change in time, their hands might get forced.

As time goes on, companies with more overt negative externalities have come under pressure—particularly in the era of ESG investing. Social pressure was behind the name changes at Total and Philip Morris. In the case of the former, the switch to TotalEnergies was meant to signal the company’s shift beyond oil and gas to include renewable energy.

In some cases, the reason why companies change their name is more subtle. GMAC (General Motors Acceptance Corporation) didn’t want to be associated with subprime lending and the subsequent multi-billion dollar bailout from the U.S. government, and a name change was one way of starting with a “clean slate”. The financial services company rebranded to Ally in 2010.

Hitting the Reset Button

Brands can become unpopular over time because of scandals, a decline in quality, or countless other reasons. When this happens, a name change can be a way of getting customers to shed those old, negative connotations.

Internet and TV providers rank dead last in customer satisfaction ratings, so it’s no surprise that many have changed their names in recent years.

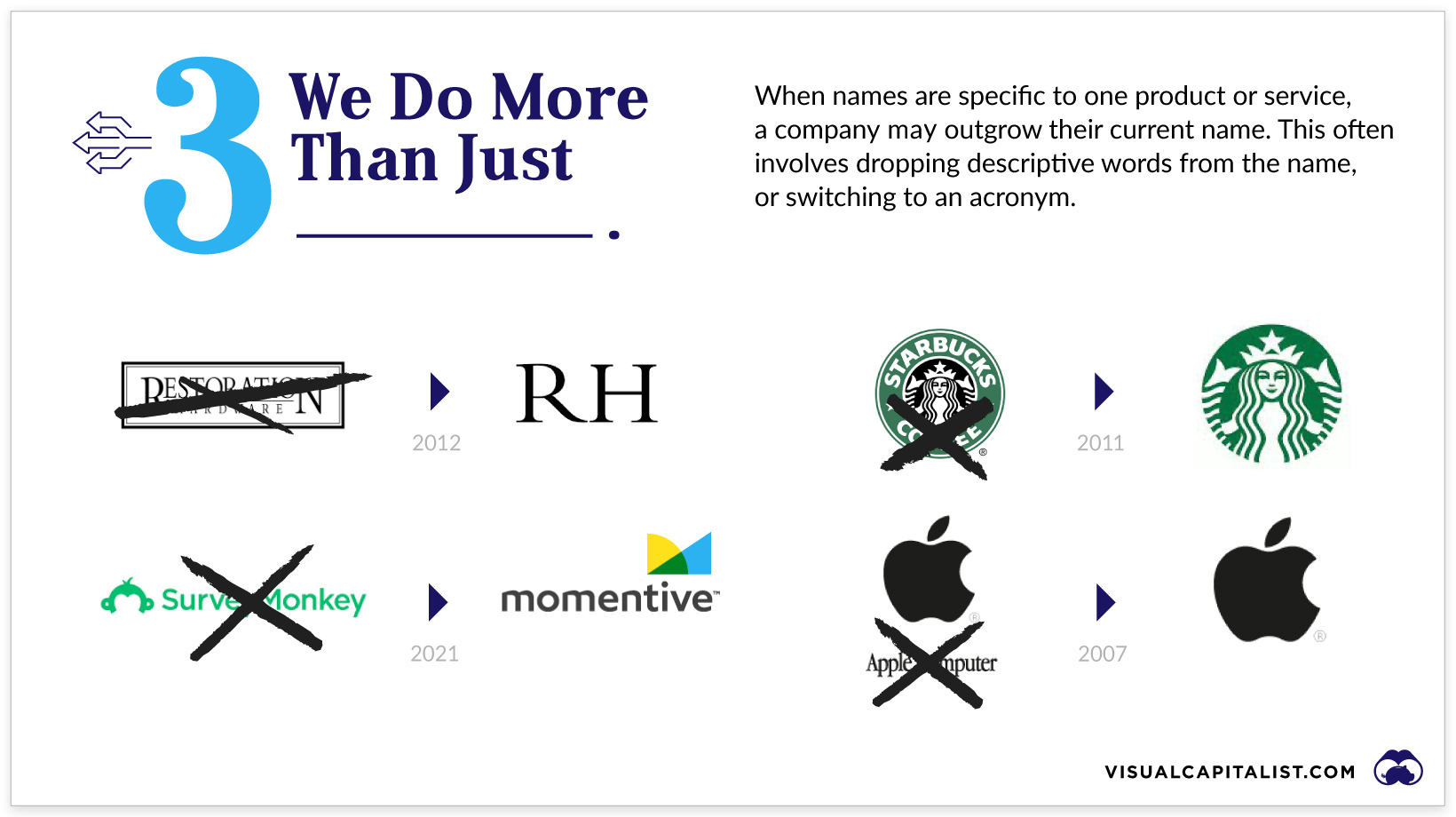

We Do More

This is a very common scenario, particularly as companies go through a rapid expansion or find success with new product offerings. After a period of sustained growth and change, a company may find that the current name is too limiting or no longer accurately reflects what the company has become.

Both Apple and Starbucks have simplified their company names over the years. The former dropped “Computers” from its name in 2007, and Starbucks dropped “Coffee” from its name in 2011. In both these cases, the name change meant disassociating the company with what initially made them successful, but in both cases it was a gamble that paid off.

One of the biggest name changes in recent years is the switch from Google to Alphabet. This name change signaled the company’s desire to expand beyond internet search and advertising.

Square also found itself in a similar situation. The “Square” brand had become synonymous with its commerce solutions, so the parent company became Block to help the company signal a shift into other areas of business.

The Start-Up Name Pivot

Another very common name change scenario is the early-stage name change.

In the world of music, there’s speculation that limited melodies and subconscious plagiarism will make creating new music increasingly difficult in the future. Similarly, there are millions of companies in the world and only so many short and snappy names. (That’s how we end up with companies called Quibi.)

Many of the popular digital services we use today started with very different names. The Google we know today was once called Backrub. Instagram began life as Bourbn, and Twitter began life as “Twittr” before finding a spare E in the scrabble pile.

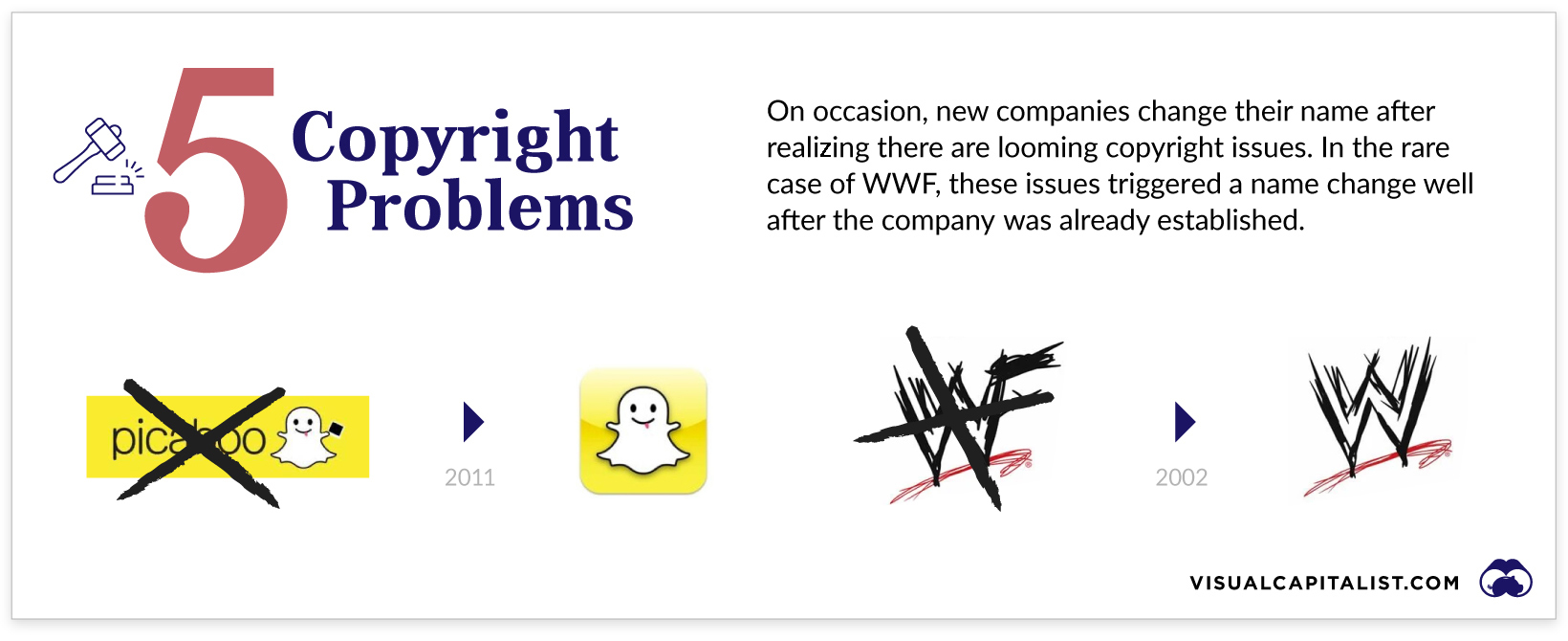

Trademark Problems

As mentioned above, many companies start out as speculative experiments or passion projects, when a viable, well-vetted name isn’t high on the priority list. As a result, new companies can run into trademark problems.

This was the case when Picaboo, the precursor of Snapchat, was forced to change their name in 2011. The existing Picaboo—a photobook company—was not thrilled to share a name with an app that was primarily associated with sexting at the time.

The fight over the name WWF was a more unique scenario. In 1994, the World Wildlife Fund and the World Wrestling Federation had a mutual agreement that the latter would stop using the initials internationally, except for fleeting uses such as “WWF champion”. In the end though, the agreement was largely ignored, and the issue became a sticking point when the wrestling company registered wwf.com. Eventually, the company rebranded as WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) after losing a lawsuit.

Course Correction

To err is human, and rebranding exercises don’t always hit the mark. When a name change is universally panned or, perhaps worse, not relevant, it’s time to course correct.

Tribune Publishing was forced to backtrack after their name change to Tronc in 2016. The widely-panned name, which was stylized in all lower case, was seen as a clumsy attempt to become a digital-first publisher.

Why Is Facebook Changing Its Name?

Facebook undertook this name change for a number of reasons, but chief among them is that the brand is irrevocably associated with scandals, negative externalities, and Mark Zuckerberg.

Even before the most recent outage and whistle-blowing scandal, Facebook was already the least-trusted tech company by a long shot. Mark Zuckerberg was once the most admired CEO in Silicon Valley, but has since fallen from grace.

It’s easy to focus on the negative triggers for the impending name change, but there is some substance behind the change as well. For one, Facebook recognizes that privacy issues have put their primary source of revenue at risk. The company’s ad-driven model built upon its users’ data is coming under increasing scrutiny with each passing year.

As well, there is substance behind the metaverse hype. Facebook first signaled their ambitions in 2014, when it acquired the virtual reality headset maker Oculus. A sizable portion of the company’s workforce is already working on making the metaverse concept a reality, and there are plans to hire 10,000 more people in Europe over the next five years.

It remains to be seen whether this immense gamble pays off, but for the near future, Zuckerberg and Facebook’s investors will be keeping a close eye on how the media and public react to the new Meta name and how the transition plays out. After all, there are billions of dollars at stake.

Technology

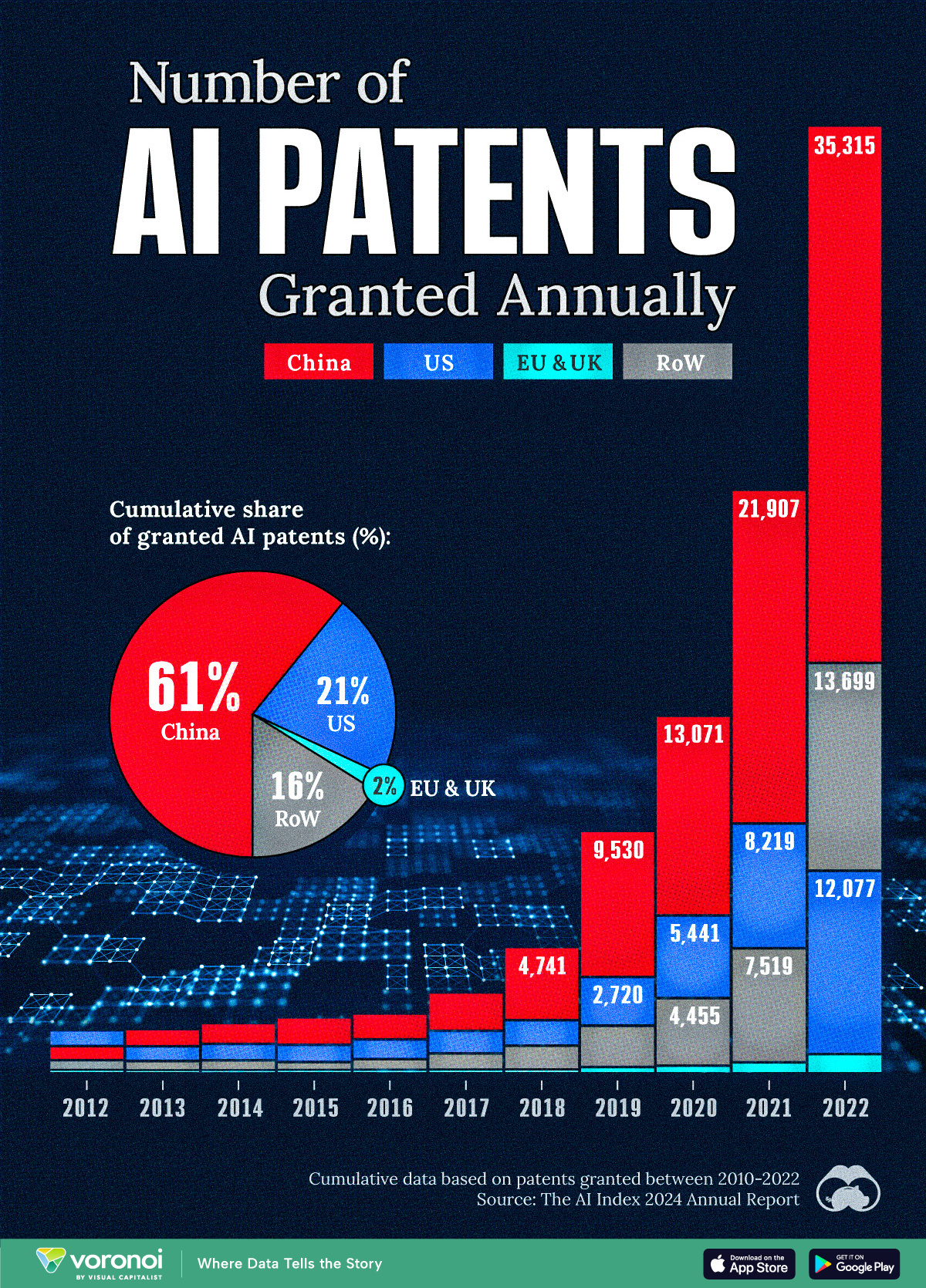

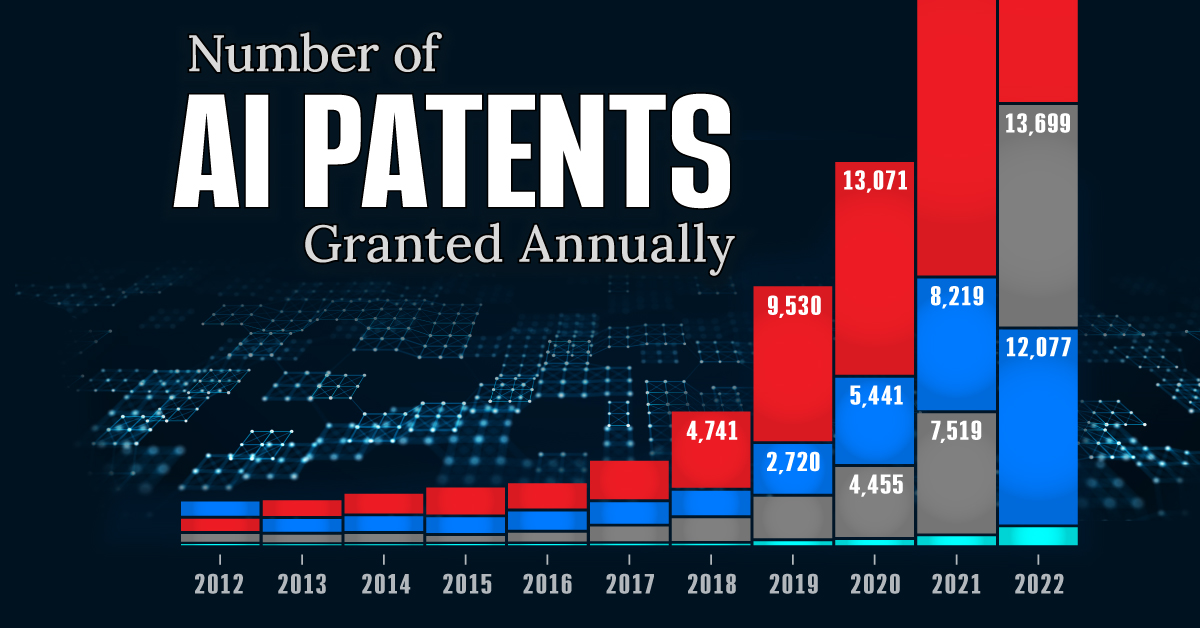

Visualizing AI Patents by Country

See which countries have been granted the most AI patents each year, from 2012 to 2022.

Visualizing AI Patents by Country

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

This infographic shows the number of AI-related patents granted each year from 2010 to 2022 (latest data available). These figures come from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), accessed via Stanford University’s 2024 AI Index Report.

From this data, we can see that China first overtook the U.S. in 2013. Since then, the country has seen enormous growth in the number of AI patents granted each year.

| Year | China | EU and UK | U.S. | RoW | Global Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 307 | 137 | 984 | 571 | 1,999 |

| 2011 | 516 | 129 | 980 | 581 | 2,206 |

| 2012 | 926 | 112 | 950 | 660 | 2,648 |

| 2013 | 1,035 | 91 | 970 | 627 | 2,723 |

| 2014 | 1,278 | 97 | 1,078 | 667 | 3,120 |

| 2015 | 1,721 | 110 | 1,135 | 539 | 3,505 |

| 2016 | 1,621 | 128 | 1,298 | 714 | 3,761 |

| 2017 | 2,428 | 144 | 1,489 | 1,075 | 5,136 |

| 2018 | 4,741 | 155 | 1,674 | 1,574 | 8,144 |

| 2019 | 9,530 | 322 | 3,211 | 2,720 | 15,783 |

| 2020 | 13,071 | 406 | 5,441 | 4,455 | 23,373 |

| 2021 | 21,907 | 623 | 8,219 | 7,519 | 38,268 |

| 2022 | 35,315 | 1,173 | 12,077 | 13,699 | 62,264 |

In 2022, China was granted more patents than every other country combined.

While this suggests that the country is very active in researching the field of artificial intelligence, it doesn’t necessarily mean that China is the farthest in terms of capability.

Key Facts About AI Patents

According to CSET, AI patents relate to mathematical relationships and algorithms, which are considered abstract ideas under patent law. They can also have different meaning, depending on where they are filed.

In the U.S., AI patenting is concentrated amongst large companies including IBM, Microsoft, and Google. On the other hand, AI patenting in China is more distributed across government organizations, universities, and tech firms (e.g. Tencent).

In terms of focus area, China’s patents are typically related to computer vision, a field of AI that enables computers and systems to interpret visual data and inputs. Meanwhile America’s efforts are more evenly distributed across research fields.

Learn More About AI From Visual Capitalist

If you want to see more data visualizations on artificial intelligence, check out this graphic that shows which job departments will be impacted by AI the most.

-

Mining1 week ago

Mining1 week agoGold vs. S&P 500: Which Has Grown More Over Five Years?

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Countries2 weeks ago

Countries2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries