Mining

Listing Requirements: From Junior Explorer to Global Mining Company

Making it to the Top: Listing Requirements From Junior Explorer to Global Mining Company

Only a few companies ever meet the listing requirements of global stock exchanges, but the effort to list can be worth it.

In 2019, Newmont produced 6.3 million ounces of gold and earned a net income of $2.9B and returned $1.4B to shareholders in dividends.

This infographic from Corvus Gold looks at the requirements and stages a mining company could face along its journey from a mineral prospect to a global mining company.

The Odds of Discovery

There are 510 million km2 (196,900,000 square miles) on the surface of the Earth and the crust is on average 40 kilometers thick (24 miles). Somewhere in there lie the next deposits of gold.

Mineral exploration companies use drill bits that range in diameter from 76-320 millimeters to explore the subsurface. The deepest drill hole is the Kola Superdeep Borehole which measured 12.2 kilometers (7.6 miles). However, most mineral exploration companies rarely drill longer than a kilometer.

Finding a gold deposit, let alone an economic one is akin to using a hair to find a needle in the proverbial haystack. To mitigate this, a typical junior mining company improves its odds by building a portfolio of properties that show potential through hints of gold and other minerals revealed from surface sampling, aerial magnetic surveys, and historic data.

Then, to dig even deeper, a company can raise capital privately for the properties that show potential. Valuations of these mineral properties are largely subjective and difficult to establish. But if the company would like to raise further capital for more expensive exploration, it can tap into stock exchanges.

Canada’s Toronto (TSX) and Venture Stock Exchanges (TSXV) sit at the center of global mining finance. Over the past five years, companies listed on TSX and TSXV completed 53% of all global mining financings, amounting to $44 billion through 6,500 transactions.

Even an idiot can make a great discovery and drive a stock from three cents to three bucks, and those guys wouldn’t get funded privately. It has to be public.

– Ross Beaty, Founder, Chairman Equinox Gold

Risk Capital: TSX-V Listing Requirements

In 2020, there were 606 companies on the TSXV that have a gold property, or a property that showed potential to host a gold deposit. These companies met a minimum set of requirements to access public markets for further funding.

At this stage, a listed mining company will deploy capital to conduct geological sampling and drilling to produce technical studies that could improve the confidence of the presence of a mineable gold deposit.

If this round of work results in an improved understanding of a gold property, a company can move from Tier 2 to Tier 1 on the TSXV, allowing it to raise further capital to increase the scope of technical and economic studies.

TSX Venture Listing Requirements:

| TSXV Tier 1 | TSXV Tier 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Property Requirements |

|

|

| Recommended Work Program |

|

|

| Working Capital |

|

|

| Net Tangible Assets |

|

|

| Capital Structure |

|

|

| Management and Board |

|

|

| Sponsorship |

|

|

| Other Criteria |

|

|

At this point, a company should have a good understanding of the costs and methods to produce a profitable operation or the value of a resource. However, early investors take their profits and new ones are needed to take a mineral property to a mining operation.

One drill hole changes the game. It’s very hard to decide who gets to make it and who doesn’t. It’s a big gate, and yet very few make it through. But you have to let them try.

– Lukas Lundin, Chairman, Lundin Group

Financing Growth: TSX Listing Requirements

To develop and construct a mine, mining companies require larger amounts for development and construction, which requires a different class of investor and stricter requirements.

In 2020, there were 133 gold companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, whose primary metal production is gold and/or own a gold property. These companies meet or exceed a set of listing requirements set out by the exchange.

The TSX has three categories of listing for mining issuers: TSX Exempt Issuers, TSX Non-Exempt Producer and TSX Non-Exempt Exploration and Development Stage. These requirements of these categories reflect the stage of development of the issuer at the time of listing. Exempt issuers are more advanced and so subject to less stringent reporting requirements.

TSX Listing Requirements:

| TSX non-exempt (Exploration & Development) | TSX non-exempt (Producer) | TSX exempt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Property Requirements |

|

|

|

| Recommended Work Program |

|

|

|

| Working Capital and Financial Resources |

|

|

|

| Net Tangible Assets |

|

|

|

| Management and Boards |

|

||

| Distribution, Market Capitalization and Public Float |

|

||

| Sponsorship |

|

|

|

| Other Criteria |

|

|

|

At this stage, bankers and lawyers set up the financing of a project based on geological and economic studies. Good financing terms can enhance the potential value of a mineral deposit and attract investors.

But sometimes, just this one listing is not enough to allow a company or project to meet its full potential.

Expanding Shareholders: NASDAQ and NYSE Listing Requirements

Companies that require more capital or to meet corporate governance rules in the countries they work in can seek a listing on additional stock exchange markets outside of their home countries. There are several benefits of additional listings:

- Gain exposure and access to more capital

- Help in improving a company’s structure of corporate governance

- Attract more and better talent

- Improves the reputation of a company

The NASDAQ and New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) can improve access to the American market. There are only 76 gold mining companies listed on the NASDAQ and NYSE exchanges.

| NASDAQ | NYSE | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-tax income | $0 to $750,000 | $2,000,000 |

| Market Capitalization | $0 to $75,000,000 | $2,000,000 |

| Total Assets and Revenue | $0 to $75,000,000 | n/a |

| Market Value of Public Float | $3,000,000 to $20,000,000 | $100,000,000 or $40,000,000 (if IPO) |

| Stockholders Equity | $4,000,000 | No more than $60,000,000 |

| Minimum Share Price | $2 to $3 | $4 |

| Operating History | 0 to 2 years | n/a |

Increased trading, world-class investors, and a well-run operation can deliver a mining company a lot of prestige and generate significant returns.

Ultimately, the continued success of the company will rely on its ability to maintain production and continue to deliver gold to the market. This all comes back to a company’s ability to find, develop, and exploit new gold deposits.

I just want to remind you that the real wealth in the mining industry is generated by FINDING something.

– Robert Friedland, Executive Chairman, Ivanhoe Mines

Building Mineral Wealth to Last

The project development timeline and mine lifecycle is a very long one. It can take decades to move from discovery to production. Each stage requires different amounts of capital and investors.

The odds of building a mine are stacked against a junior mining company—but for the few that grow through the listing process requirements, they can become the next great investment.

A mineral discovery is rare, but a successful gold mining company is even rarer.

Lithium

Ranked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

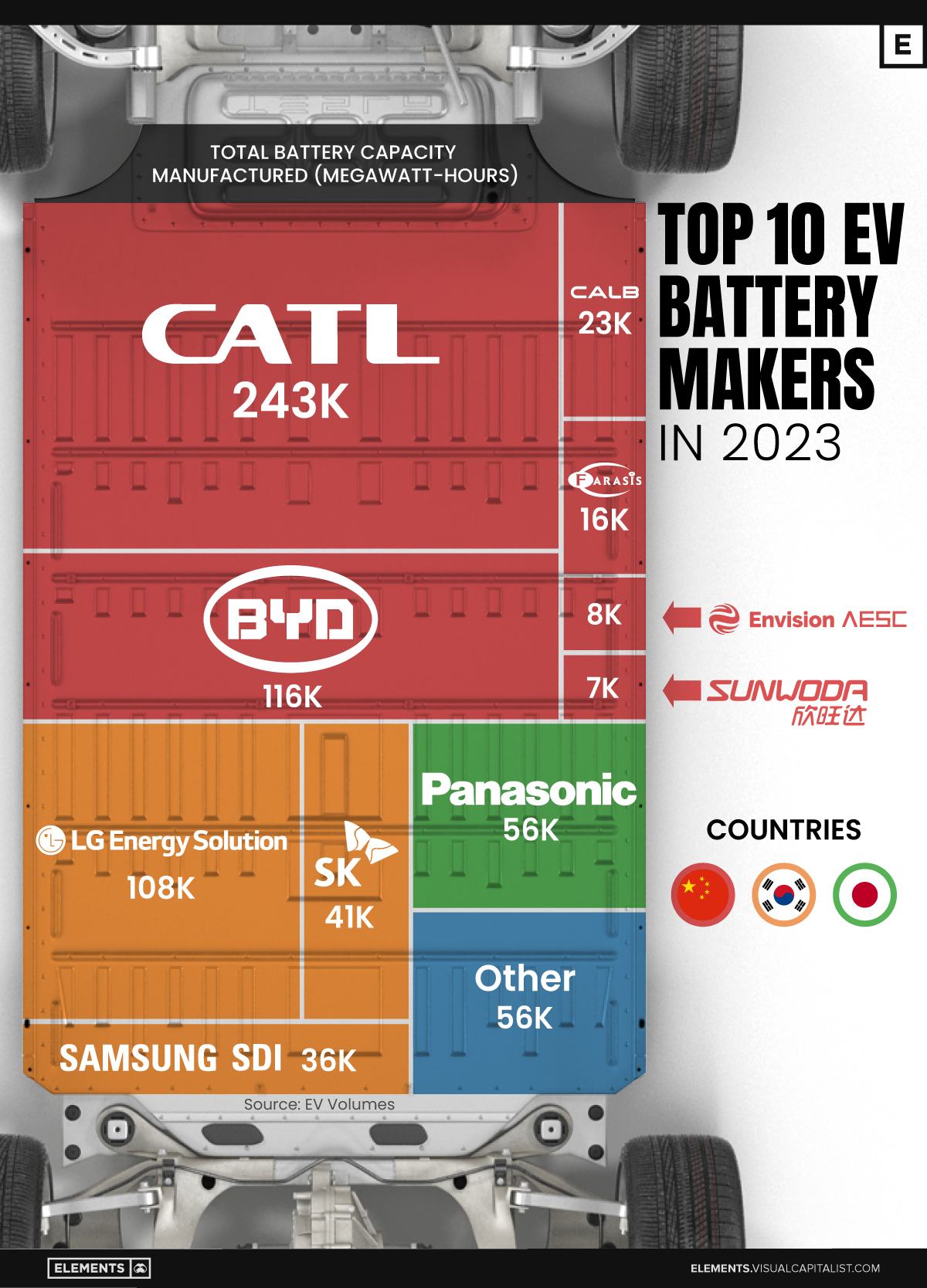

Asia dominates this ranking of the world’s largest EV battery manufacturers in 2023.

The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Despite efforts from the U.S. and EU to secure local domestic supply, all major EV battery manufacturers remain based in Asia.

In this graphic we rank the top 10 EV battery manufacturers by total battery deployment (measured in megawatt-hours) in 2023. The data is from EV Volumes.

Chinese Dominance

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) has swiftly risen in less than a decade to claim the title of the largest global battery group.

The Chinese company now has a 34% share of the market and supplies batteries to a range of made-in-China vehicles, including the Tesla Model Y, SAIC’s MG4/Mulan, and various Li Auto models.

| Company | Country | 2023 Production (megawatt-hour) | Share of Total Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL | 🇨🇳 China | 242,700 | 34% |

| BYD | 🇨🇳 China | 115,917 | 16% |

| LG Energy Solution | 🇰🇷 Korea | 108,487 | 15% |

| Panasonic | 🇯🇵 Japan | 56,560 | 8% |

| SK On | 🇰🇷 Korea | 40,711 | 6% |

| Samsung SDI | 🇰🇷 Korea | 35,703 | 5% |

| CALB | 🇨🇳 China | 23,493 | 3% |

| Farasis Energy | 🇨🇳 China | 16,527 | 2% |

| Envision AESC | 🇨🇳 China | 8,342 | 1% |

| Sunwoda | 🇨🇳 China | 6,979 | 1% |

| Other | - | 56,040 | 8% |

In 2023, BYD surpassed LG Energy Solution to claim second place. This was driven by demand from its own models and growth in third-party deals, including providing batteries for the made-in-Germany Tesla Model Y, Toyota bZ3, Changan UNI-V, Venucia V-Online, as well as several Haval and FAW models.

The top three battery makers (CATL, BYD, LG) collectively account for two-thirds (66%) of total battery deployment.

Once a leader in the EV battery business, Panasonic now holds the fourth position with an 8% market share, down from 9% last year. With its main client, Tesla, now sourcing batteries from multiple suppliers, the Japanese battery maker seems to be losing its competitive edge in the industry.

Overall, the global EV battery market size is projected to grow from $49 billion in 2022 to $98 billion by 2029, according to Fortune Business Insights.

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoThe Highest Earning Athletes in Seven Professional Sports

-

Countries2 weeks ago

Countries2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

-

United States2 weeks ago

United States2 weeks agoWhere U.S. Inflation Hit the Hardest in March 2024

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoTop Countries By Forest Growth Since 2001

-

United States2 weeks ago

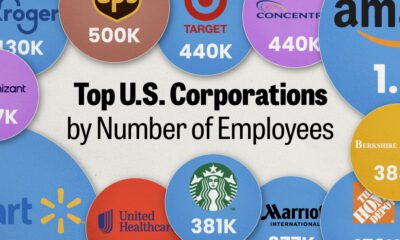

United States2 weeks agoRanked: The Largest U.S. Corporations by Number of Employees

-

Maps2 weeks ago

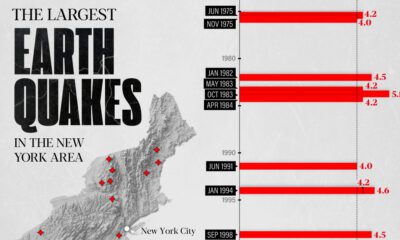

Maps2 weeks agoThe Largest Earthquakes in the New York Area (1970-2024)