Brands

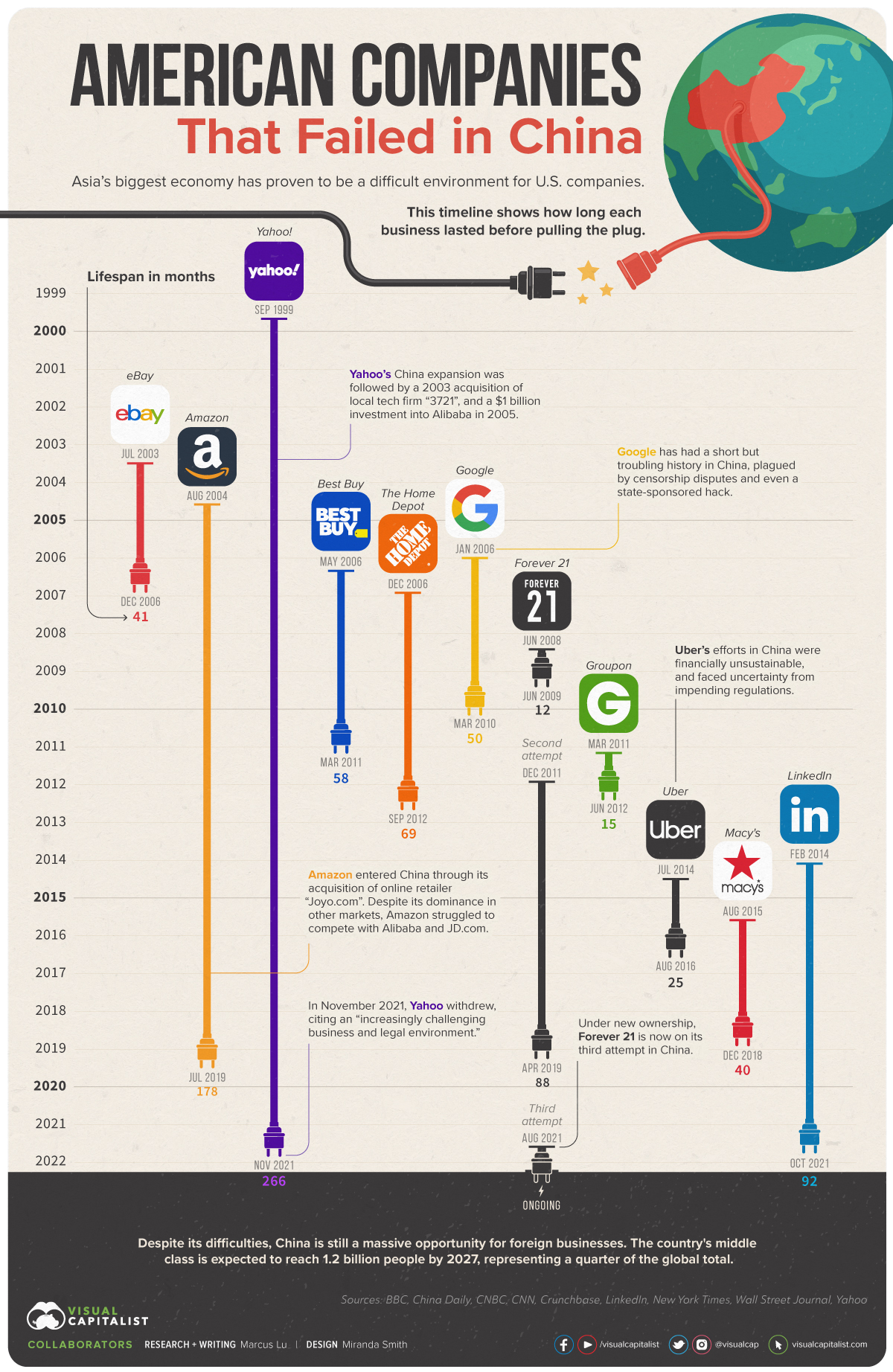

American Companies That Failed in China

American Companies That Failed in China

For decades, China has been a top priority for American companies looking to expand.

This is because the country’s middle class is simply enormous, growing from 3.1% to 50.8% of the country’s total population between the years 2000 and 2018. According to Brookings, there are now at least 700 million people in China’s middle class, and this group has never had more disposable income to spend on consumer goods and services.

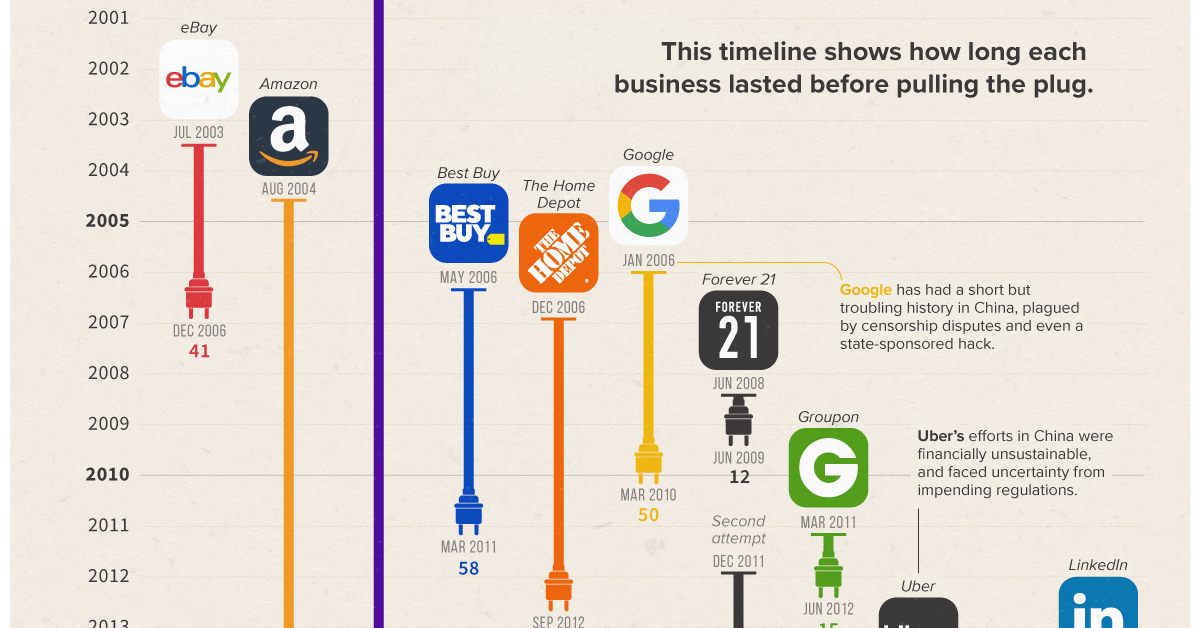

Despite the size and potential of the market, China is not an easy place for foreign businesses to enter. As this infographic shows, many of America’s biggest names eventually admitted defeat.

Companies by Tenure

The following table lists the tenures of every company included in the graphic.

It’s worth noting that Google’s parent company, Alphabet, still maintains a physical presence in China. Google’s services were banned by the Chinese government in 2010.

| Company | Enter Date | Exit Date | Tenure in months |

|---|---|---|---|

| eBay | July 2003 | December 2006 | 41 |

| Amazon | August 2004 | July 2019 | 178 |

| Yahoo! | September 1999 | November 2021 | 266 |

| Best Buy | May 2006 | March 2011 | 58 |

| The Home Depot | December 2006 | September 2012 | 69 |

| January 2006 | March 2010 | 50 | |

| Forever 21 (1st attempt) | June 2008 | June 2009 | 12 |

| Forever 21 (2nd attempt) | December 2011 | April 2019 | 88 |

| Forever 21 (3rd attempt) | August 2021 | Ongoing | Ongoing |

| Groupon | March 2011 | June 2012 | 15 |

| Uber | July 2014 | August 2016 | 25 |

| Macy's | August 2015 | December 2018 | 40 |

| February 2014 | October 2021 | 92 |

Dates were gathered from various media reports and sources. There may be small deviations from when a company actually entered or exited.

The reasons for why these companies withdrew are surprisingly similar, and can be broken down into two broad categories.

Retailers Fail to Adapt

Failing to adapt to the cultural differences of Chinese consumers is a common mistake. Here’s how two American retailers learned this lesson the hard way.

Best Buy

Best Buy struggled because Chinese consumers were not willing to pay a premium for brand-name electronics. Local retailers could often source similar (or counterfeit) goods for much cheaper, and undercut Best Buy’s prices.

“Why buy a Sony DVD player or Nokia phone at Best Buy when you can pay less for the exact same product at a local store?”

– Shaun Rein, China Market Research Group

Best Buy also made the mistake of bringing over its large flagship stores, which were out of reach for most consumers. Due to severe traffic congestion, locals preferred smaller shops that were closer to home.

Home Depot

The Home Depot expanded into China around the same time as Best Buy, but unfortunately it was another cultural mismatch.

Home Depot failed to acknowledge that “do it yourself” repairs are not a strong cultural match for China. Labor costs are relatively low, so rather than do the work themselves, many homeowners prefer to rather hire someone else to do it. On the other side of the equation, the American brand failed to win over contractors doing the repairs and renovations.

The Home Depot’s product offerings were also left unchanged from America, making them a poor match for local tastes. As a point of comparison, IKEA has had a presence in China since 1998, and continues to open new stores to this day.

Tech Firms Clash with Regulators

Uber’s experiences in China make a good case study on how American tech firms struggle to succeed in Asia’s biggest economy.

For starters, breaking into the Chinese market was incredibly expensive. Uber spent billions on subsidies to attract customers and drivers, and losses were quickly piling up. To make matters worse, domestic rivals like DiDi were also handing out subsidies.

On the operational side, Uber ran into several hurdles. To avoid issues with China’s data localization laws, the company needed servers on Chinese soil. Its navigation provider, Google Maps, also had limited accuracy in the country. This left Uber with no choice but to partner with Baidu, a Chinese tech company.

The final straw, however, was likely a set of impending regulations which targeted the ride-hailing industry. Under these rules, Uber risked losing control of its data, and would need both provincial and national regulatory approvals for its activities. Even further, subsidies would also no longer be allowed.

Uber realized that doing business in China was unsustainable, but its exit wasn’t exactly a failure. In 2016, Uber sold its assets to rival DiDi and took an 18.8% stake in the company. Ironically, DiDi is now embroiled in a conflict with Chinese regulators over its listing on the NYSE.

The Tech Fallout Continues

Since Uber’s departure, the Chinese government has increased their grip over the tech industry. This has driven more American firms out of the country, including Yahoo and LinkedIn, which is now owned by Microsoft.

Both firms announced their withdrawals in 2021 and were rather clear about why they made the decision. Yahoo cited its commitment to a “free and open” internet, while LinkedIn says its decision was due to a “considerably more difficult operating environment and higher regulatory requirements”.

Given the geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, companies that generate data (often seen as a national security concern) are likely to continue facing regulatory hurdles.

Outside of tech, China is still a massive opportunity for American businesses. By 2027, the country’s middle class is expected to reach 1.2 billion people, or one quarter of the global total.

Business

Charted: How the Logos of Select Fashion Brands Have Evolved

For some fashion brands, changing logos mirror the constant loop of reinvention, over decades of building products, markets, and consumer bases.

Charted: How the Logos of Select Fashion Brands Have Evolved

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

A global fashion brand needs to balance maintaining a consistent style built painstakingly over the years while adapting to current trends. And for some of them, their changing logos reflect the loop of reinvention, over decades of building products, markets, and consumer bases.

We illustrate the evolution of six fashion companies’ logos over time. Data for the visualization and article is sourced from 1000logos.net.

Nike & Adidas: A Tale of Two Shoe Companies

The world’s largest footwear company, Nike began its journey as Blue Ribbon Sports in 1964. In 1971, they rebranded as Nike, inspired by the Greek goddess of victory.

The famous swoosh logo was designed in 1971 by Carolyn Davidson, at the time a Portland State University graphic design student. She was paid $35 dollars for her work (about $270 today). Twelve years later, Nike co-founder Phil Knight have her 500 Nike shares that have remained unsold.

Here’s how often some of the world’s biggest fashion brands have changed their logos since founding.

| Brand | Logo Changes |

|---|---|

| 👟 Adidas | 10 |

| 👖 Levi's | 8 |

| ✔️ Nike | 4 |

| 👕 Gap | 4 |

| 🐊 Lacoste | 3 |

| 👗 Zara | 3 |

Meanwhile, Adidas has far older origins: all the way back to 1920 Germany. Founded by Adolf Dassler, the company split into Adidas and Puma in 1947.

Dassler bought the iconic three stripes from another German sports company in 1947. In 1952, the stripes debuted on Adidas footwear at the Summer Olympics.

Currently, Adidas has several concurrent logos depending on the product line. This includes: the horizontal across a trefoil (Adidas Originals), curved across a circle (Adidas Style) or the diagonal mountain above the brand name (Adidas Performance).

-

United States7 days ago

United States7 days agoMapped: Countries Where Recreational Cannabis is Legal

-

Healthcare2 weeks ago

Healthcare2 weeks agoLife Expectancy by Region (1950-2050F)

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Growth of a $1,000 Equity Investment, by Stock Market

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoMapped: Europe’s GDP Per Capita, by Country

-

Money2 weeks ago

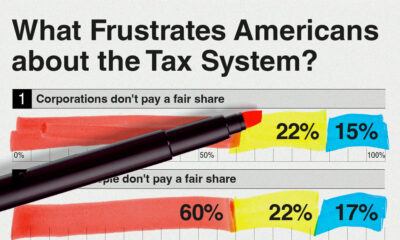

Money2 weeks agoCharted: What Frustrates Americans About the Tax System

-

Technology2 weeks ago

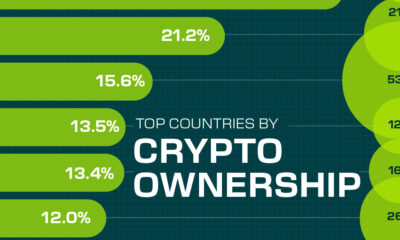

Technology2 weeks agoCountries With the Highest Rates of Crypto Ownership

-

Mining2 weeks ago

Mining2 weeks agoWhere the World’s Aluminum is Smelted, by Country

-

Personal Finance2 weeks ago

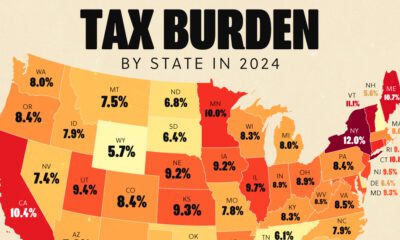

Personal Finance2 weeks agoVisualizing the Tax Burden of Every U.S. State