Markets

Warren Buffett’s Biggest Wins & Fails

Warren Buffett’s investing track record is nearly impeccable.

Over his lifetime, Buffett has built Berkshire Hathaway into one of the biggest companies in American history, amassed a personal fortune of over $80 billion, and earned acclaim as one of the world’s foremost philanthropists.

But in a 75-year career, it’s no surprise that even Buffett has made the odd blunder – and there’s one that he claims has ultimately costed him an estimated $200 billion!

The Warren Buffett Series

Part 4: Buffett’s Biggest Wins and Fails

Today’s infographic highlights Buffett’s investing strokes of genius, as well as a few decisions he would take back.

It’s the fourth part of the Warren Buffett Series, which we’ve done in partnership with finder.com, a personal finance site that helps people make better decisions – whether they want to dabble in cryptocurrencies or become the next famous value investor.

Note: New series parts will be released intermittently. Stay tuned for future parts with our free mailing list.

How did Buffett go from local paperboy to the world’s most iconic investor?

Here are the backstories behind five of Warren’s biggest acts of genius. These are the events and decisions that would propel his name into investing folklore for centuries to come.

Buffett’s 5 Biggest Wins

From making shrewd value investing calls to taking advantage of misfortune in the salad oil market, here are some of the stories that are Buffett classics:

1. GEICO (1951)

At 20 years old, Buffett was attending Columbia Business School, and was a student of Benjamin Graham’s.

When young Buffett learned that Graham was on the board of the Government Employees Insurance Company (GEICO), he immediately took a train to Washington, D.C. to visit the company’s headquarters.

On a Saturday, Buffett banged on the door of the building until a janitor let him in, and Buffett met Lorimer Davidson – the future CEO of GEICO. Ultimately, Davidson spent four hours talking to this “highly unusual young man”.

He answered my questions, taught me the insurance business and explained to me the competitive advantage that GEICO had. That afternoon changed my life.

– Warren Buffett

By Monday, Buffett was “more excited about GEICO than any other stock in [his] life” and started buying it on the open market. He put 65% of his small fortune of $20,000 into GEICO, and the money he earned from the deal would provide a solid foundation for Buffett’s future fortune.

Although Buffett sold GEICO after locking in solid gains, the stock would rise as much as 100x over time. Buffett bought his favorite stock again a few years later, loaded up further during the 1970s, and eventually bought the whole company in the 1990s.

2. Sanborn Maps (1960)

This early deal may not be Buffett’s biggest – but it’s the clearest case of Benjamin Graham’s influence on his style.

Sanborn Maps had a lucrative business around making city maps for insurers, but eventually its mapping business started dying – and the falling stock price reflected this trend.

Buffett, after diving deep into the company’s financials, realized that Sanborn had a large investment portfolio that was built up over the company’s stronger years. Sanborn’s stock was worth $45 per share, but the value of the company’s investments tallied to $65 per share.

In other words, these investments held by the company were alone worth more than the stock – and that didn’t include the actual value of the map business itself!

Buffett accumulated the stock in 1958 and 1959, eventually putting 35% of his partnership assets in it. Then, he became a director, and convinced other shareholders to use the investment portfolio to buy out stockholders. He walked away with a 50% profit.

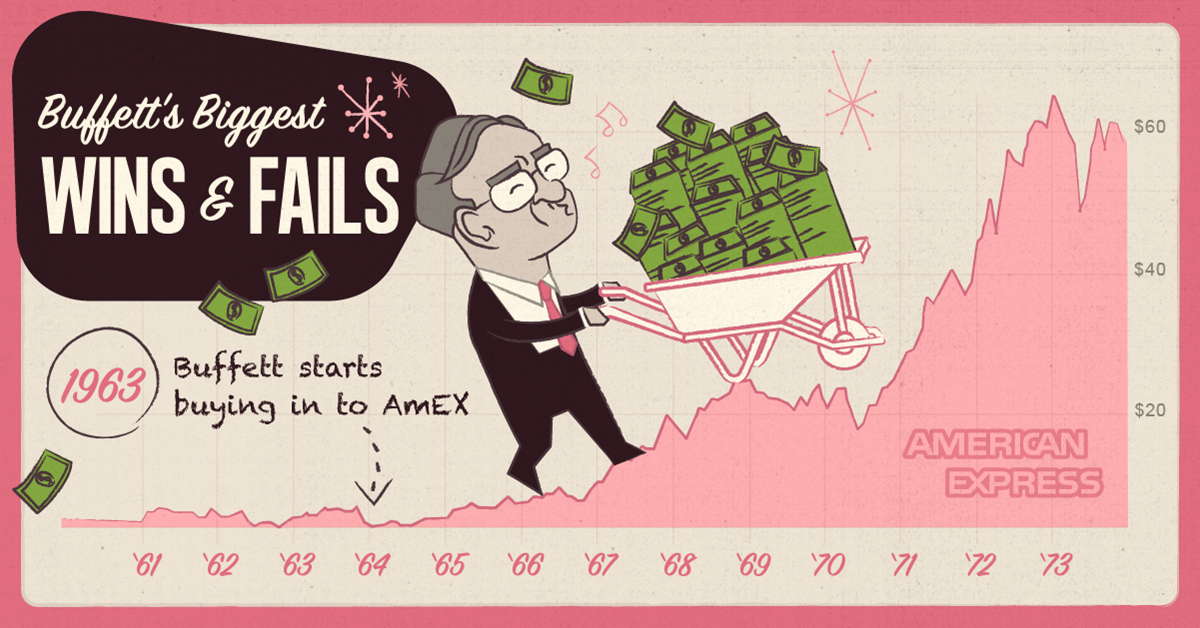

3. The Salad Oil Swindle (1963)

For a value investor like Buffett, every mishap is a potential opportunity.

And in 1963, a con artist named Anthony “Tino” De Angelis inadvertently set Buffett up for a massive home run. After De Angelis attempted to corner the soybean oil market using false inventories and loans, the market subsequently collapsed.

American Express – the world’s largest credit card company at the time – got caught up in the disaster, and its stock price halved as investors thought the company would fail.

Although everyone else panicked, Buffett knew the scandal wouldn’t affect the overall value of the business. He was right – and bought 5% of American Express for $20 million. By 1973, Buffett’s investment increased ten times in value.

4. Capital Cities / ABC (1985)

In the 1980s, corporate raiders and takeover madness reigned supreme.

The massive TV network ABC found itself vulnerable, and sold itself to a company that promised to keep its legacy intact. Capital Cities, a relative unknown and a fraction of the size, had somehow managed to buy ABC.

The CEO of Cap Cities, Tom Murphy – one of Buffett’s favorite managers in the world – gave Warren a call:

Pal, you’re not going to believe this. I’ve just bought ABC. You’ve got to come and tell me how I’m going to pay for it.

– Tom Murphy, Capital Cities CEO

Berkshire dropped $500 million to finance the deal. This turned Buffett into Murphy’s much-needed “900-lb gorilla” – a loyal shareholder that would hold onto shares regardless of price, as Murphy figured out how to turn the company around.

It turned out to be a fantastic gamble for Buffett, as Capital Cities/ABC sold to Disney for $19 billion in 1995.

5. Freddie Mac (1988)

Buffett started loading up on shares of Freddie Mac in 1988 for $4 per share.

By 2000, Buffett noticed the company was taking unnecessary risks to deliver double-digit growth. This risk, and its short-term focus, turned Buffett off the company. As a result, at a share price close to $70, he sold virtually all of his holdings, enjoying a return of more than 1,500%.

I figure if you see just one cockroach, there’s probably a lot.

– Warren Buffett

Later on, Freddie Mac’s business would collapse in the housing crisis, only to be taken over by the U.S. federal government. Today, its stock sells for a mere $1.50 per share.

Buffett’s Blunders

Over the course of 75 years, it’s not surprising that even Buffett has made some serious mistakes. Here are his costliest ones:

1. Berkshire Hathaway (1962)

When Buffett first invested in Berkshire Hathaway, it was a fledgling textile company.

Buffett eventually tried to pull out, but the company changed the terms of the deal at the last minute. Buffett was spiteful, and loaded up with enough stock to fire the CEO that deceived him.

The textiles business was terrible and sucked up capital – and Berkshire unintentionally would become Buffett’s holding company for other deals. This mistake, he estimates, costed him an estimated $200 billion.

2. Dexter Shoes (1993)

Dexter Shoe Co. had a long, profitable history, an enduring franchise, and suberb management. In other words, it was the exact kind of company Buffett liked.

Buffett dropped $433 million in 1993 to buy the company, but the company’s competitive advantage soon waned. To make matters worse, Warren Buffett financed the deal with Berkshire’s own stock, compounding the mistake hugely. It ended up costing the company $3.5 billion.

To date, Dexter is the worst deal that I’ve made. But I’ll make more mistakes in the future – you can bet on that.

– Warren Buffett

Later on, Buffett would say that this deal deserved a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records as a top financial disaster.

3. Amazon.com (2000s)

Buffett says not buying Amazon was one of his biggest mistakes.

I did not think [founder Jeff Bezos] could succeed on the scale he has. [I] underestimated the brilliance of the execution.

– Warren Buffett

Given that Amazon has shot up in value to become one of the most valuable companies in the world, and that Jeff Bezos is by now the far richest person globally, it’s fair to say this whiff continues to haunt Buffett to this day.

Markets

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

U.S. debt interest payments have surged past the $1 trillion dollar mark, amid high interest rates and an ever-expanding debt burden.

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

The cost of paying for America’s national debt crossed the $1 trillion dollar mark in 2023, driven by high interest rates and a record $34 trillion mountain of debt.

Over the last decade, U.S. debt interest payments have more than doubled amid vast government spending during the pandemic crisis. As debt payments continue to soar, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that debt servicing costs surpassed defense spending for the first time ever this year.

This graphic shows the sharp rise in U.S. debt payments, based on data from the Federal Reserve.

A $1 Trillion Interest Bill, and Growing

Below, we show how U.S. debt interest payments have risen at a faster pace than at another time in modern history:

| Date | Interest Payments | U.S. National Debt |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $1.0T | $34.0T |

| 2022 | $830B | $31.4T |

| 2021 | $612B | $29.6T |

| 2020 | $518B | $27.7T |

| 2019 | $564B | $23.2T |

| 2018 | $571B | $22.0T |

| 2017 | $493B | $20.5T |

| 2016 | $460B | $20.0T |

| 2015 | $435B | $18.9T |

| 2014 | $442B | $18.1T |

| 2013 | $425B | $17.2T |

| 2012 | $417B | $16.4T |

| 2011 | $433B | $15.2T |

| 2010 | $400B | $14.0T |

| 2009 | $354B | $12.3T |

| 2008 | $380B | $10.7T |

| 2007 | $414B | $9.2T |

| 2006 | $387B | $8.7T |

| 2005 | $355B | $8.2T |

| 2004 | $318B | $7.6T |

| 2003 | $294B | $7.0T |

| 2002 | $298B | $6.4T |

| 2001 | $318B | $5.9T |

| 2000 | $353B | $5.7T |

| 1999 | $353B | $5.8T |

| 1998 | $360B | $5.6T |

| 1997 | $368B | $5.5T |

| 1996 | $362B | $5.3T |

| 1995 | $357B | $5.0T |

| 1994 | $334B | $4.8T |

| 1993 | $311B | $4.5T |

| 1992 | $306B | $4.2T |

| 1991 | $308B | $3.8T |

| 1990 | $298B | $3.4T |

| 1989 | $275B | $3.0T |

| 1988 | $254B | $2.7T |

| 1987 | $240B | $2.4T |

| 1986 | $225B | $2.2T |

| 1985 | $219B | $1.9T |

| 1984 | $205B | $1.7T |

| 1983 | $176B | $1.4T |

| 1982 | $157B | $1.2T |

| 1981 | $142B | $1.0T |

| 1980 | $113B | $930.2B |

| 1979 | $96B | $845.1B |

| 1978 | $84B | $789.2B |

| 1977 | $69B | $718.9B |

| 1976 | $61B | $653.5B |

| 1975 | $55B | $576.6B |

| 1974 | $50B | $492.7B |

| 1973 | $45B | $469.1B |

| 1972 | $39B | $448.5B |

| 1971 | $36B | $424.1B |

| 1970 | $35B | $389.2B |

| 1969 | $30B | $368.2B |

| 1968 | $25B | $358.0B |

| 1967 | $23B | $344.7B |

| 1966 | $21B | $329.3B |

Interest payments represent seasonally adjusted annual rate at the end of Q4.

At current rates, the U.S. national debt is growing by a remarkable $1 trillion about every 100 days, equal to roughly $3.6 trillion per year.

As the national debt has ballooned, debt payments even exceeded Medicaid outlays in 2023—one of the government’s largest expenditures. On average, the U.S. spent more than $2 billion per day on interest costs last year. Going further, the U.S. government is projected to spend a historic $12.4 trillion on interest payments over the next decade, averaging about $37,100 per American.

Exacerbating matters is that the U.S. is running a steep deficit, which stood at $1.1 trillion for the first six months of fiscal 2024. This has accelerated due to the 43% increase in debt servicing costs along with a $31 billion dollar increase in defense spending from a year earlier. Additionally, a $30 billion increase in funding for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in light of the regional banking crisis last year was a major contributor to the deficit increase.

Overall, the CBO forecasts that roughly 75% of the federal deficit’s increase will be due to interest costs by 2034.

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Popular Smartphone Brands in the U.S.

-

Misc1 week ago

Misc1 week agoAlmost Every EV Stock is Down After Q1 2024

-

Money1 week ago

Money1 week agoWhere Does One U.S. Tax Dollar Go?

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoRanked: Top Countries by Total Forest Loss Since 2001

-

Real Estate2 weeks ago

Real Estate2 weeks agoVisualizing America’s Shortage of Affordable Homes

-

Maps2 weeks ago

Maps2 weeks agoMapped: Average Wages Across Europe

-

Mining2 weeks ago

Mining2 weeks agoCharted: The Value Gap Between the Gold Price and Gold Miners

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoVisualizing the Size of the Global Senior Population