Markets

Picking Investments is Nothing Like Buying a New Car

As consumers, we are used to researching the many choices we have before making a buying decision.

For most people, the process of buying a new product (such as a car) might look something like this:

- Recognize a need

- Search for information

- Evaluate options

- Make a purchase

- Evaluate satisfaction with purchase

In other words, we figure out what we need, and then we seek to learn more about our choices. After reviewing relevant articles, product ratings, buyer reviews, and other sources of information, we can make a final and informed decision.

Same Process For Picking Investments?

Does the above process look similar to how you approach investing, particularly in choosing funds?

If so, Vanguard says it might be worth re-framing how you look at things. Here’s why picking investments is different.

Vanguard, which manages over $3.5 trillion in assets, may have a good point.

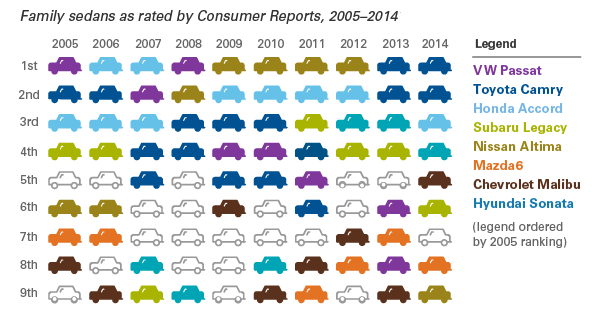

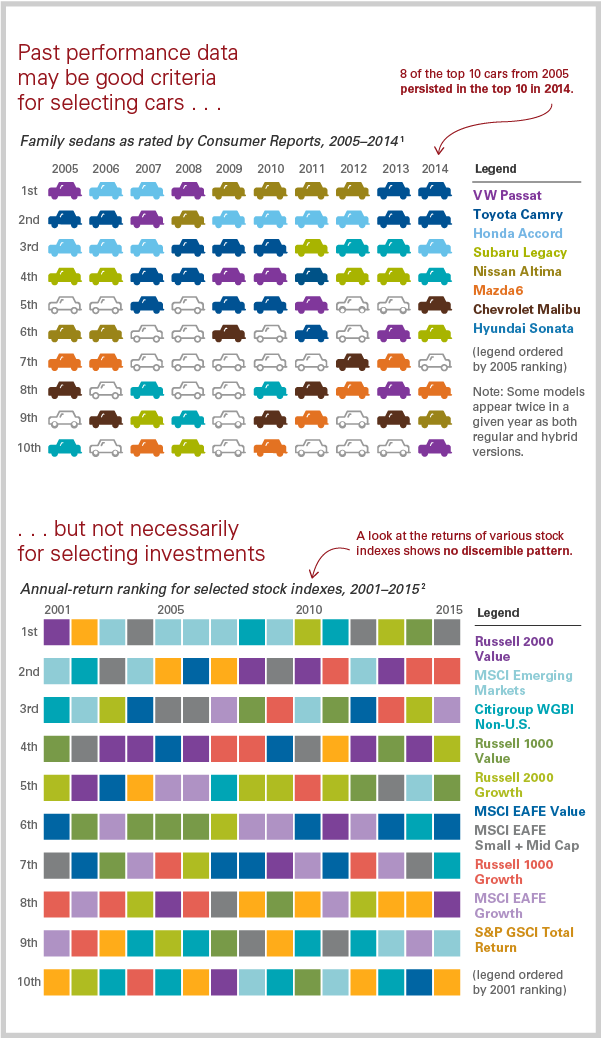

The past performance of a car model is hugely important to a consumer’s decision. That’s because the next Honda Civic built in the factory is guaranteed to be much like previous Honda Civics before it.

For investments, however, everyone knows that past performance does not predict future results. And even though this advice is ubiquitous in the investing world, it is still commonly ignored by many investors.

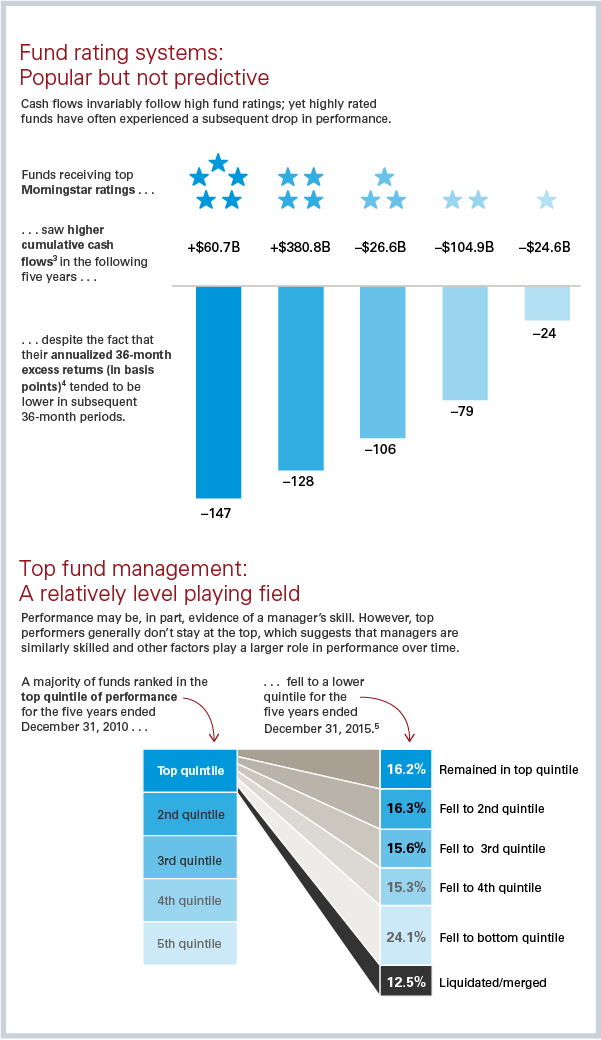

Here’s what happens to top performing funds:

Even though top funds did well in previous years, there isn’t much correlation with the future.

In the above case, top-rated funds got an influx of capital, which made it harder to get the same return. Funds rated five stars by Morningstar received $60.7 billion in new inflows, but dropped 147 basis points in annualized returns in their subsequent 36 month periods.

The other reason for this is that fund management is just a relatively level playing field, and it’s hard to stay a top performer over the long-term.

The best funds leading up to 2010 were all over the place for the next five years, and only 16.2% of them continued to be top performers. Meanwhile, an astonishing 24.1% of the top performing funds fell to the bottom performing quintile, while 12.5% of funds were liquidated or merged.

Keeping this all in mind, Vanguard recommends adopting a different process for picking investments:

We can’t say we disagree for almost any type of portfolio.

Markets

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

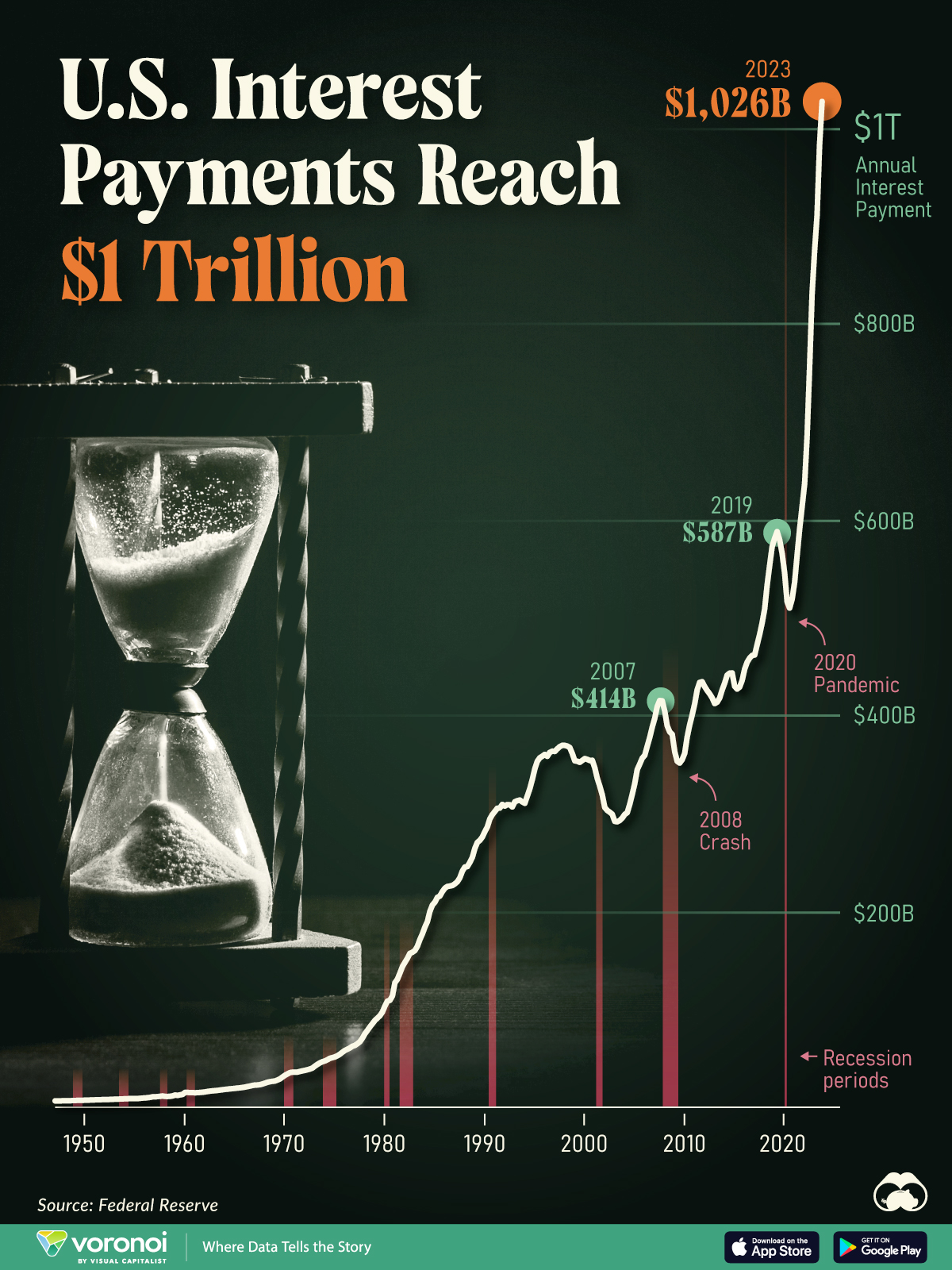

U.S. debt interest payments have surged past the $1 trillion dollar mark, amid high interest rates and an ever-expanding debt burden.

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

The cost of paying for America’s national debt crossed the $1 trillion dollar mark in 2023, driven by high interest rates and a record $34 trillion mountain of debt.

Over the last decade, U.S. debt interest payments have more than doubled amid vast government spending during the pandemic crisis. As debt payments continue to soar, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that debt servicing costs surpassed defense spending for the first time ever this year.

This graphic shows the sharp rise in U.S. debt payments, based on data from the Federal Reserve.

A $1 Trillion Interest Bill, and Growing

Below, we show how U.S. debt interest payments have risen at a faster pace than at another time in modern history:

| Date | Interest Payments | U.S. National Debt |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $1.0T | $34.0T |

| 2022 | $830B | $31.4T |

| 2021 | $612B | $29.6T |

| 2020 | $518B | $27.7T |

| 2019 | $564B | $23.2T |

| 2018 | $571B | $22.0T |

| 2017 | $493B | $20.5T |

| 2016 | $460B | $20.0T |

| 2015 | $435B | $18.9T |

| 2014 | $442B | $18.1T |

| 2013 | $425B | $17.2T |

| 2012 | $417B | $16.4T |

| 2011 | $433B | $15.2T |

| 2010 | $400B | $14.0T |

| 2009 | $354B | $12.3T |

| 2008 | $380B | $10.7T |

| 2007 | $414B | $9.2T |

| 2006 | $387B | $8.7T |

| 2005 | $355B | $8.2T |

| 2004 | $318B | $7.6T |

| 2003 | $294B | $7.0T |

| 2002 | $298B | $6.4T |

| 2001 | $318B | $5.9T |

| 2000 | $353B | $5.7T |

| 1999 | $353B | $5.8T |

| 1998 | $360B | $5.6T |

| 1997 | $368B | $5.5T |

| 1996 | $362B | $5.3T |

| 1995 | $357B | $5.0T |

| 1994 | $334B | $4.8T |

| 1993 | $311B | $4.5T |

| 1992 | $306B | $4.2T |

| 1991 | $308B | $3.8T |

| 1990 | $298B | $3.4T |

| 1989 | $275B | $3.0T |

| 1988 | $254B | $2.7T |

| 1987 | $240B | $2.4T |

| 1986 | $225B | $2.2T |

| 1985 | $219B | $1.9T |

| 1984 | $205B | $1.7T |

| 1983 | $176B | $1.4T |

| 1982 | $157B | $1.2T |

| 1981 | $142B | $1.0T |

| 1980 | $113B | $930.2B |

| 1979 | $96B | $845.1B |

| 1978 | $84B | $789.2B |

| 1977 | $69B | $718.9B |

| 1976 | $61B | $653.5B |

| 1975 | $55B | $576.6B |

| 1974 | $50B | $492.7B |

| 1973 | $45B | $469.1B |

| 1972 | $39B | $448.5B |

| 1971 | $36B | $424.1B |

| 1970 | $35B | $389.2B |

| 1969 | $30B | $368.2B |

| 1968 | $25B | $358.0B |

| 1967 | $23B | $344.7B |

| 1966 | $21B | $329.3B |

Interest payments represent seasonally adjusted annual rate at the end of Q4.

At current rates, the U.S. national debt is growing by a remarkable $1 trillion about every 100 days, equal to roughly $3.6 trillion per year.

As the national debt has ballooned, debt payments even exceeded Medicaid outlays in 2023—one of the government’s largest expenditures. On average, the U.S. spent more than $2 billion per day on interest costs last year. Going further, the U.S. government is projected to spend a historic $12.4 trillion on interest payments over the next decade, averaging about $37,100 per American.

Exacerbating matters is that the U.S. is running a steep deficit, which stood at $1.1 trillion for the first six months of fiscal 2024. This has accelerated due to the 43% increase in debt servicing costs along with a $31 billion dollar increase in defense spending from a year earlier. Additionally, a $30 billion increase in funding for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in light of the regional banking crisis last year was a major contributor to the deficit increase.

Overall, the CBO forecasts that roughly 75% of the federal deficit’s increase will be due to interest costs by 2034.

-

Maps2 weeks ago

Maps2 weeks agoMapped: Average Wages Across Europe

-

Money1 week ago

Money1 week agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

Real Estate1 week ago

Real Estate1 week agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Markets1 week ago

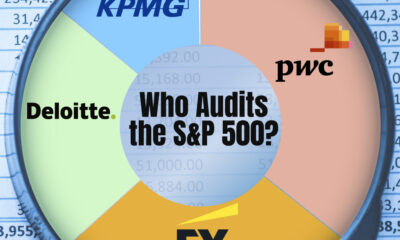

Markets1 week agoCharted: Big Four Market Share by S&P 500 Audits

-

AI1 week ago

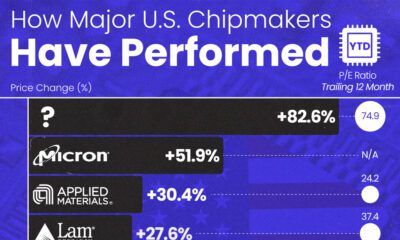

AI1 week agoThe Stock Performance of U.S. Chipmakers So Far in 2024

-

Automotive2 weeks ago

Automotive2 weeks agoAlmost Every EV Stock is Down After Q1 2024

-

Money2 weeks ago

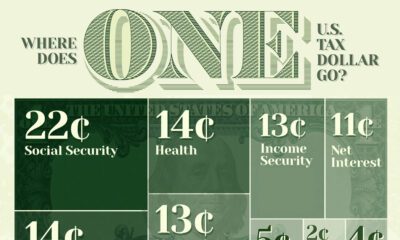

Money2 weeks agoWhere Does One U.S. Tax Dollar Go?

-

Green2 weeks ago

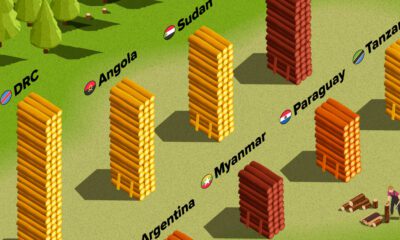

Green2 weeks agoRanked: Top Countries by Total Forest Loss Since 2001