Money

How Central Banks Think About Digital Currency

How Central Banks Think About Digital Currency

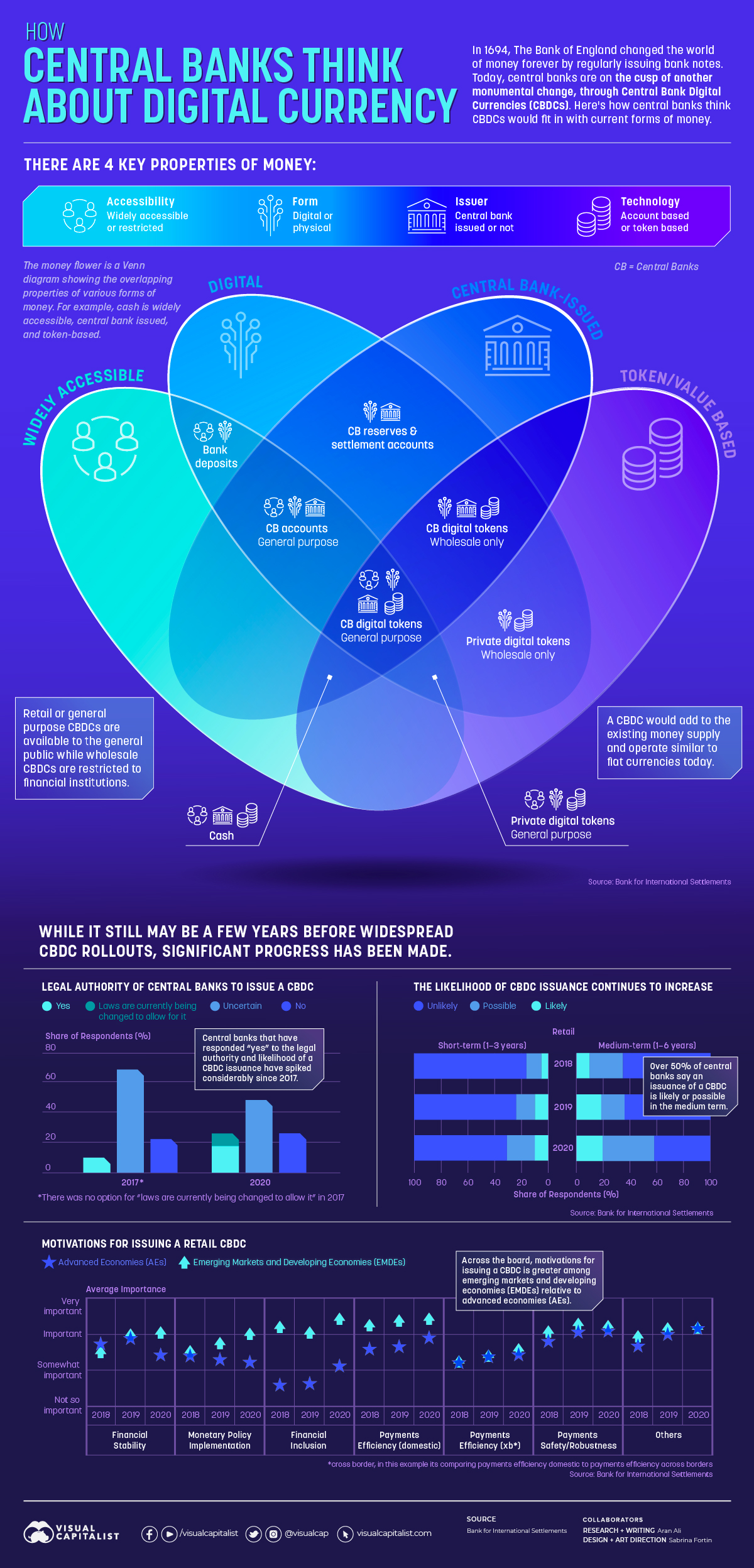

In the late 1600s, the introduction of bank notes changed the financial system forever. Fast forward to today, and another monumental change is expected to occur through central bank digital currencies (CBDC).

A CBDC adopts certain characteristics of everyday paper or coin currencies and cryptocurrency. It is expected to provide central banks and the monetary systems they govern a step towards modernizing.

But what exactly are CBDCs and how do they differ from money we use today?

The ABCs of CBDCs

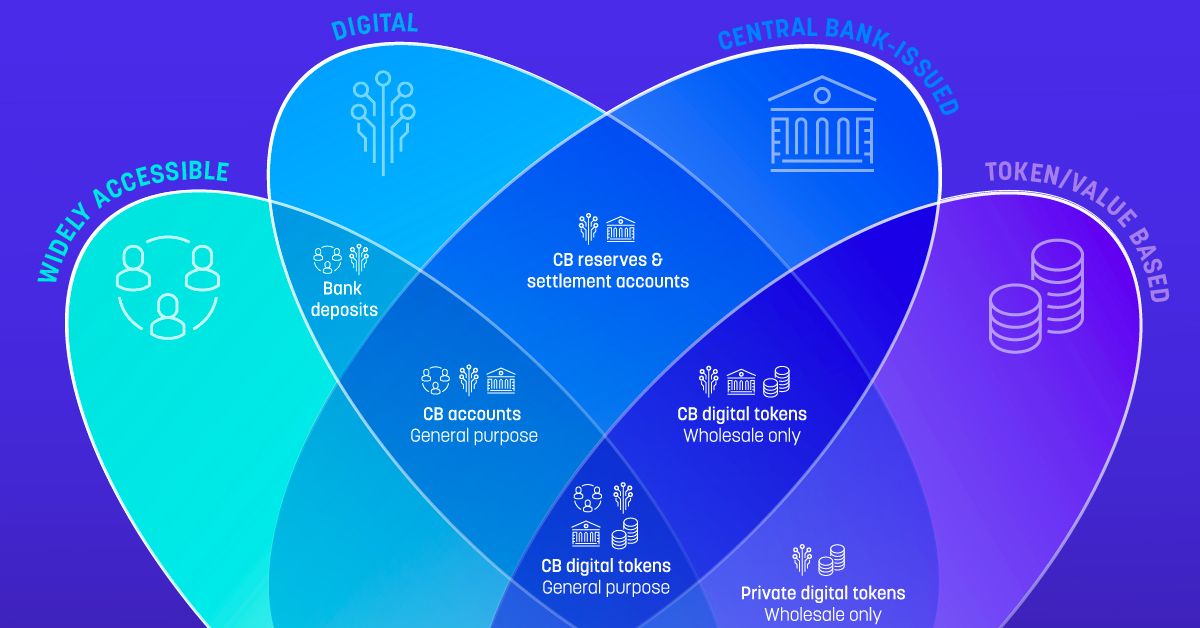

To better understand a CBDC, it helps to first understand the taxonomy of money and its overlapping properties.

For example, the properties of cash are that it’s accessible, physical and digital, central bank issued, and token-based. Here’s how the taxonomy of money breaks down:

- Accessibility: The accessibility of money is a big factor in determining its place within the taxonomy of money. For instance, cash and general purpose CBDCs are considered widely accessible.

- Form: Is the money physical or digital? The form of money determines distribution and the potential for dilution, and future CBDCs issued will be completely digital.

- Issuer: Where does the money come from? CBDCs are to be issued by the central bank and backed by their respective governments, which differs from cryptocurrencies which mostly have no government affiliations.

- Technology: How does the currency work? CBDCs break down into token-based and account-based approaches. A token-based CBDC operates like banknotes today, where your information is not known nor needed by a cashier when accepting your payment. An account-based system, however, requires authorization to partake on the network, akin to paying with a digital wallet or card.

Digital Currency vs Digital Coins

In essence, digital currency is the electronic form of banknotes that exists today. Therefore, it’s viewed by some as a modern and efficient version of the cash you hold in your wallet or purse.

On the other hand, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are a store of value like gold that is secured by encryption. Cryptocurrencies are privately owned and fueled by blockchain technology, compared to digital currencies which do not use decentralized ledgers or blockchain technology.

Digital Currency: Regulatory Authority and Stability

Digital currencies are issued by a central bank, and therefore, are backed by the full power of a government. According to the Bank for International Settlements, over 20% of central banks surveyed say they have legal authority in issuing a CBDC. Almost 10% more said laws are currently being changed to allow for it.

As more central banks issue digital currencies, there’s likely to be favorability between them. This is similar to how a few currencies like the U.S. dollar and Euro dominate the currency landscape.

The Benefits of Issuing a CBDC

There are several positives regarding the issuance of a CBDC over other currencies.

First, the cost of retail payments in the U.S. is estimated to be between 0.5% and 0.9% of the country’s $20 trillion in GDP. Digital currencies can flow much more effectively between parties, helping reduce these transaction fees.

Second, large chunks of the global population are still considered unbanked. In this case, a CBDC opens avenues for people to access the global financial system without a bank. Even today, 6% of Americans do not have a single bank account.

Other motivations for a CBDC include:

- Financial stability

- Monetary policy implementation

- Increased safety, efficiency, and robustness

- Limit on illicit activity

An example of payments efficiency can be seen during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when some Americans failed to receive their stimulus check. Altogether, some $2 billion in funds have gone unclaimed. A functioning rollout of a CBDC and a more direct relationship with citizens would minimize such a problem.

Status of CBDCs

Although widespread adoption of CBDCs is still far away, research and experiments are making notable strides forward:

- 81 countries representing 90% of global GDP are exploring CBDCs.

- The share of central banks actively engaging in CBDC work grew to 86% in the last 4 years.

- 60% of central banks are conducting experiments on CBDCs (up from 42% in 2019) and 14% are moving forward to development and pilot arrangement.

- The Bahamas is one of five countries currently working with a CBDC – the Bahamian Sand Dollar.

- Sweden and Uruguay have shown interest in a digital currency. Sweden began testing an “e-krona” in 2020, and Uruguay announced tests to issue digital Uruguayan pesos as far back as 2017.

- The People’s Bank of China has been running CBDC tests since April 2020. In all, tens of thousands of citizens have participated, spending 2 billion yuan, and the country is poised to be the first to fully launch a CBDC.

The U.K. central bank is less optimistic about a rolling out a CBDC in the near future. The proposed digital currency—dubbed “Britcoin”—is unlikely to arrive until at least 2025.

Disrupting The World of Money

Wherever you look, technology is disrupting finance and upending the status quo.

This can be seen through the rising market value of fintech firms, which in some cases are trumping traditional financial institutions in value. It is also evident in the rapid rise of Bitcoin to a $1 trillion market cap, making it the fastest asset to do so.

With the rollout of central bank digital currencies on the horizon, the next disruption of financial systems is already beginning.

Demographics

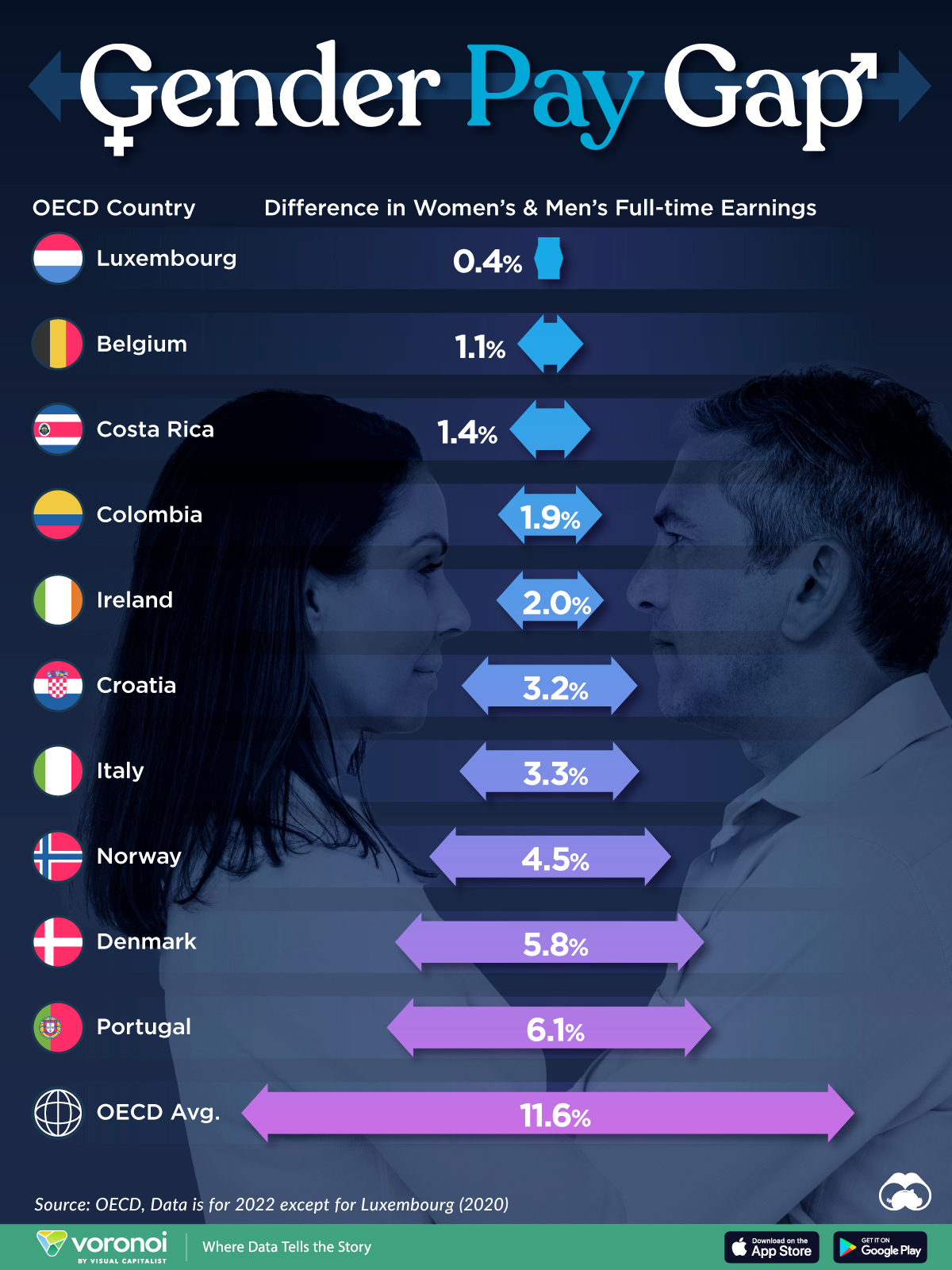

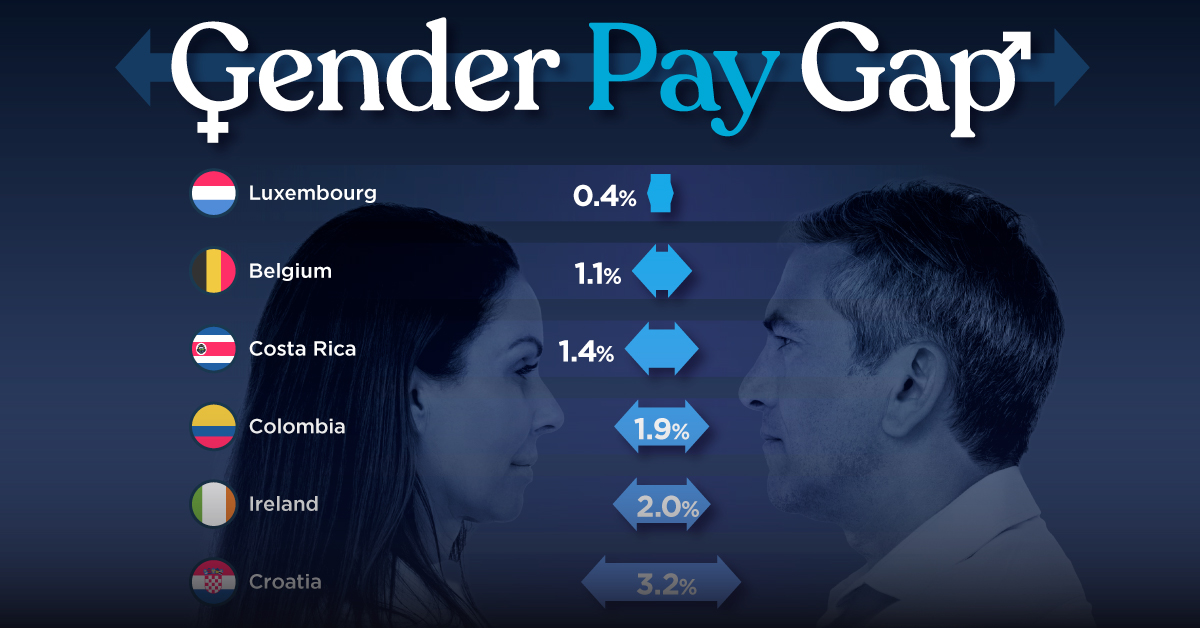

The Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

Which OECD countries have the smallest gender wage gaps? We look at the 10 countries with gaps lower than the average.

The Smallest Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Among the 38 member countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), several have made significant strides in addressing income inequality between men and women.

In this graphic we’ve ranked the OECD countries with the 10 smallest gender pay gaps, using the latest data from the OECD for 2022.

The gender pay gap is calculated as the difference between median full-time earnings for men and women divided by the median full-time earnings of men.

Which Countries Have the Smallest Gender Pay Gaps?

Luxembourg’s gender pay gap is the lowest among OECD members at only 0.4%—well below the OECD average of 11.6%.

| Rank | Country | Percentage Difference in Men's & Women's Full-time Earnings |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 🇱🇺 Luxembourg | 0.4% |

| 2 | 🇧🇪 Belgium | 1.1% |

| 3 | 🇨🇷 Costa Rica | 1.4% |

| 4 | 🇨🇴 Colombia | 1.9% |

| 5 | 🇮🇪 Ireland | 2.0% |

| 6 | 🇭🇷 Croatia | 3.2% |

| 7 | 🇮🇹 Italy | 3.3% |

| 8 | 🇳🇴 Norway | 4.5% |

| 9 | 🇩🇰 Denmark | 5.8% |

| 10 | 🇵🇹 Portugal | 6.1% |

| OECD Average | 11.6% |

Notably, eight of the top 10 countries with the smallest gender pay gaps are located in Europe, as labor equality laws designed to target gender differences have begun to pay off.

The two other countries that made the list were Costa Rica (1.4%) and Colombia (1.9%), which came in third and fourth place, respectively.

How Did Luxembourg (Nearly) Eliminate its Gender Wage Gap?

Luxembourg’s virtually-non-existent gender wage gap in 2020 can be traced back to its diligent efforts to prioritize equal pay. Since 2016, firms that have not complied with the Labor Code’s equal pay laws have been subjected to penalizing fines ranging from €251 to €25,000.

Higher female education rates also contribute to the diminishing pay gap, with Luxembourg tied for first in the educational attainment rankings of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index Report for 2023.

See More Graphics about Demographics and Money

While these 10 countries are well below the OECD’s average gender pay gap of 11.6%, many OECD member countries including the U.S. are significantly above the average. To see the full list of the top 10 OECD countries with the largest gender pay gaps, check out this visualization.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoAmerica’s Top Companies by Revenue (1994 vs. 2023)

-

Environment1 week ago

Environment1 week agoRanked: Top Countries by Total Forest Loss Since 2001

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoVisualizing America’s Shortage of Affordable Homes

-

Maps2 weeks ago

Maps2 weeks agoMapped: Average Wages Across Europe

-

Mining2 weeks ago

Mining2 weeks agoCharted: The Value Gap Between the Gold Price and Gold Miners

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

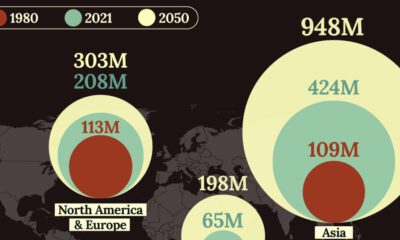

Demographics2 weeks agoVisualizing the Size of the Global Senior Population

-

Misc2 weeks ago

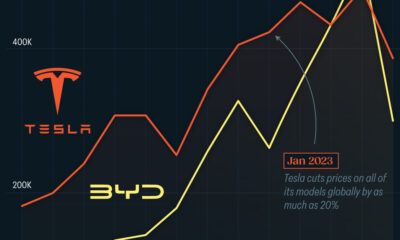

Misc2 weeks agoTesla Is Once Again the World’s Best-Selling EV Company

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Popular Smartphone Brands in the U.S.