Markets

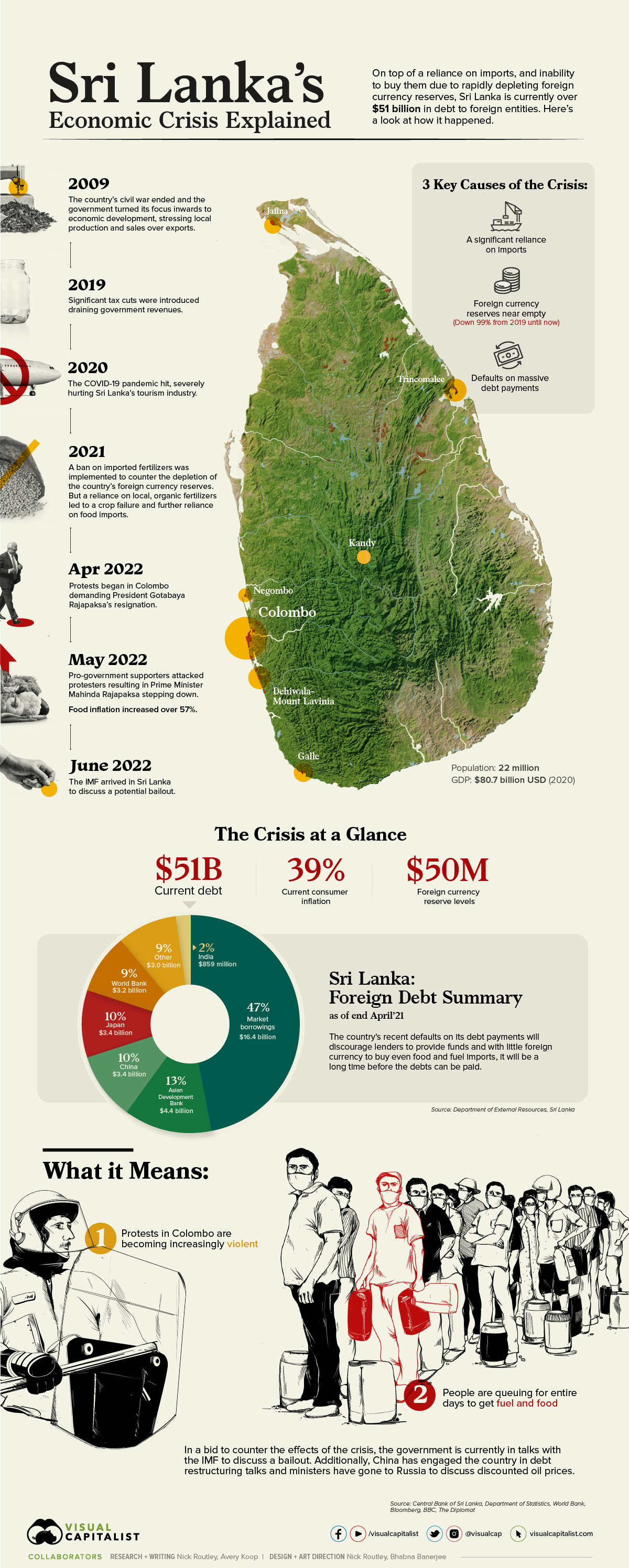

News Explainer: The Economic Crisis in Sri Lanka

Explained: the Economic Crisis in Sri Lanka

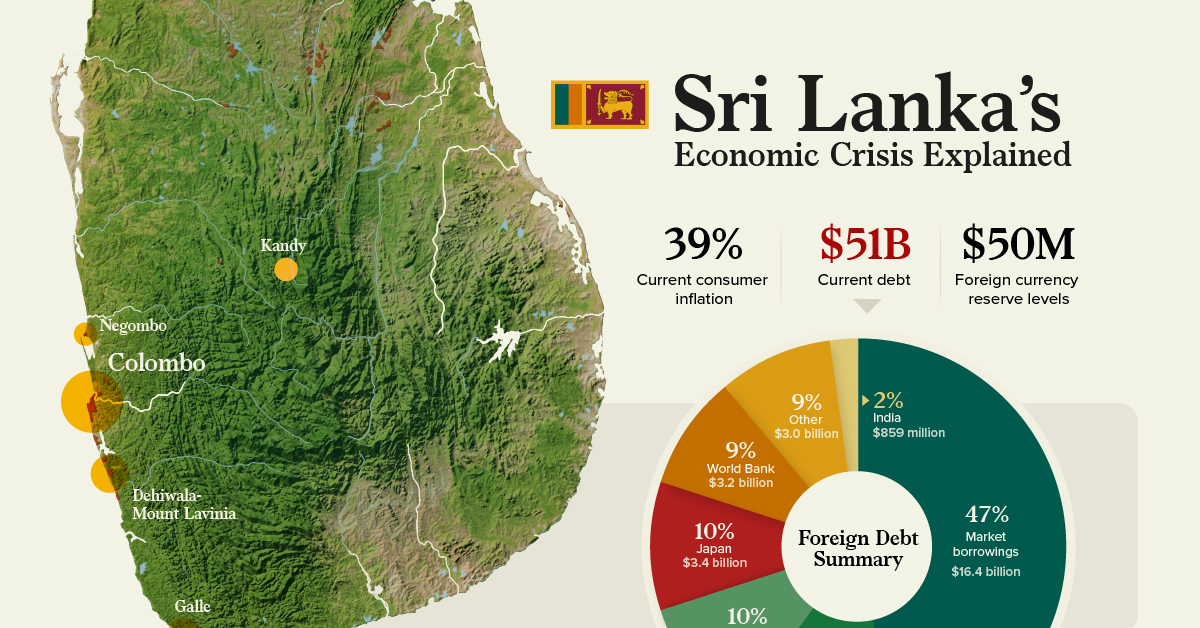

Sri Lanka is currently in an economic and political crisis of mass proportions, recently culminating in a default on its debt payments. The country is also nearly at empty on their foreign currency reserves, decreasing the ability to purchase imports and driving up domestic prices for goods.

There are several reasons for this crisis and the economic turmoil has sparked mass protests and violence across the country. This visual breaks down some of the elements that led to Sri Lanka’s current situation.

A Timeline of Events

The ongoing problems in Sri Lanka have bubbled up after years of economic mismanagement. Here’s a brief timeline looking at just some of the recent factors.

2009

In 2009, a decades-long civil war in the country ended and the government’s focus turned inward towards domestic production. However, a stress on local production and sales, instead of exports, increased the reliance on foreign goods.

2019

Unprompted cuts were introduced on income tax in 2019, leading to significant losses in government revenue, draining an already cash-strapped country.

2020

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the world causing border closures globally and stifling one of Sri Lanka’s most lucrative industries. Prior to the pandemic, in 2018, tourism contributed nearly 5% of the country’s GDP and generated over 388,000 jobs. In 2020, tourism’s share of GDP had dropped to 0.8%, with over 40,000 jobs lost to that point.

2021

Recently, the Sri Lankan government introduced a ban on foreign-made chemical fertilizers. The ban was meant to counter the depletion of the country’s foreign currency reserves.

However, with only local, organic fertilizers available to farmers, a massive crop failure occurred and Sri Lankans were subsequently forced to rely even more heavily on imports, further depleting reserves.

April 2022

In early April this year, massive protests calling for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation, sparked in Sri Lanka’s capital city, Colombo.

May 2022

In May, pro-government supporters brutally attacked protesters. Subsequently, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, brother of President Rajapaksa, stepped down and was replaced with former PM, Ranil Wickremesinghe.

June 2022

Recently, the government approved a four-day work week to allow citizens an extra day to grow food, as prices continue to shoot up. Food inflation increased over 57% in May.

Additionally, the increasing prices on grain caused by the war in Ukraine and rising fuel prices globally have played into an already dire situation in Sri Lanka.

The Key Information

“Our economy has completely collapsed.”

Prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to Parliament last week.

One of the main causes of the economic crisis in Sri Lanka is the reliance on imports and the amount spent on them. Let’s take a look at the numbers:

- 2021 total imports = $20.6 billion USD

- 2022 total imports (to March) = $5.7 billion USD

In contrast, the most recent reported foreign currency reserve levels in the country were at an abysmal $50 million, having plummeted an astounding 99%, from $7.6 billion in 2019.

Some of the top imports in 2021, according to the country’s central bank were:

- Refined petroleum = $2.8 billion

- Textiles = $3.1 billion

- Chemical products = $1.1 billion

- Food & beverage = $1.7 billion

Of course, without the cash to purchase these goods from abroad, Sri Lankans face an increasingly drastic situation.

Additionally, the debt Sri Lanka has incurred is huge, further hampering their ability to boost their reserves. Recently, they defaulted on a $78 million loan from international creditors, and in total, they’ve borrowed $50.7 billion.

The largest source of their debt is by far due to market borrowings, followed closely by loans taken from the Asian Development Bank, China, and Japan, among others.

What it Means

Sri Lanka is home to more than 22 million people who are rapidly losing the ability to purchase everyday goods. Consumer inflation reached 39% at the end of May.

Due to power outages meant to save energy and fuel, schools are currently shuttered and children have nowhere to go during the day. Protesters calling for the president’s resignation have been camped in the capital for months, facing tear gas from police and backlash from president Rajapaksa’s supporters, but many have also responded violently to pushback.

India and China have agreed to send help to the country and the the International Monetary Fund recently arrived in the country to discuss a bailout. Additionally, the government has sent ministers to Russia to discuss a deal for discounted oil imports.

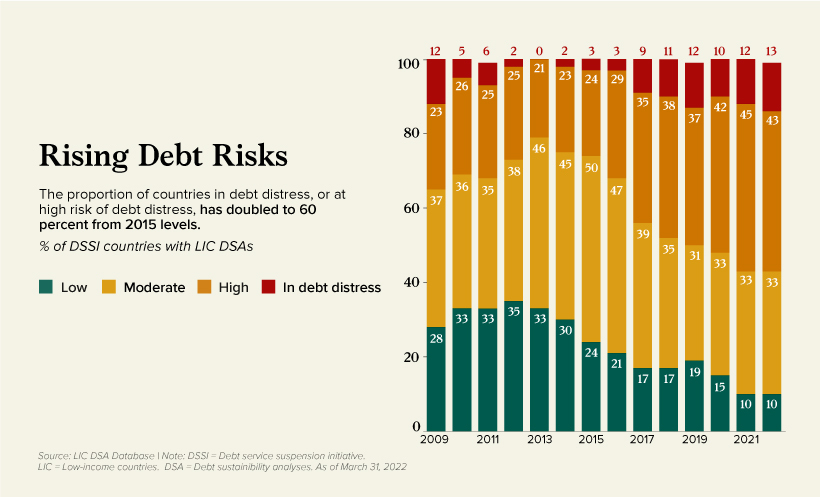

A Foreshadowing for Low Income Countries

Governments need foreign currency in order to purchase goods from abroad. Without the ability to purchase or borrow foreign currency, the Sri Lankan government cannot buy desperately needed imports, including food staples and fuel, causing domestic prices to rise.

Furthermore, defaults on loan payments discourage foreign direct investment and devalue the national currency, making future borrowing more difficult.

What’s happening in Sri Lanka may be an ominous preview of what’s to come in other low and middle-income countries, as the risk of debt distress continues to rise globally.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) was implemented by G20 countries, suspending nearly $13 billion in debt from the start of the pandemic until late 2021.

Some DSSI and LIC countries facing a high risk of debt distress include Zambia, Ethiopia, and Tajikistan, to name a few.

Going forward, Sri Lanka’s next steps in managing this situation will either serve as a useful example for other countries at risk or a warning worth heeding.

Ongoing Updates

Since this article was published the situation has changed significantly in Sri Lanka. Protesters have received their original demand calling for president Rajapaksa to step down — both he and prime minister Wickremesinghe have agreed to resign. This comes after protesters stormed the president’s palace causing him to flee the country.

Note: The debt breakdown in the main visualization represents total outstanding external debt owed to foreign creditors rather total debt.

Markets

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

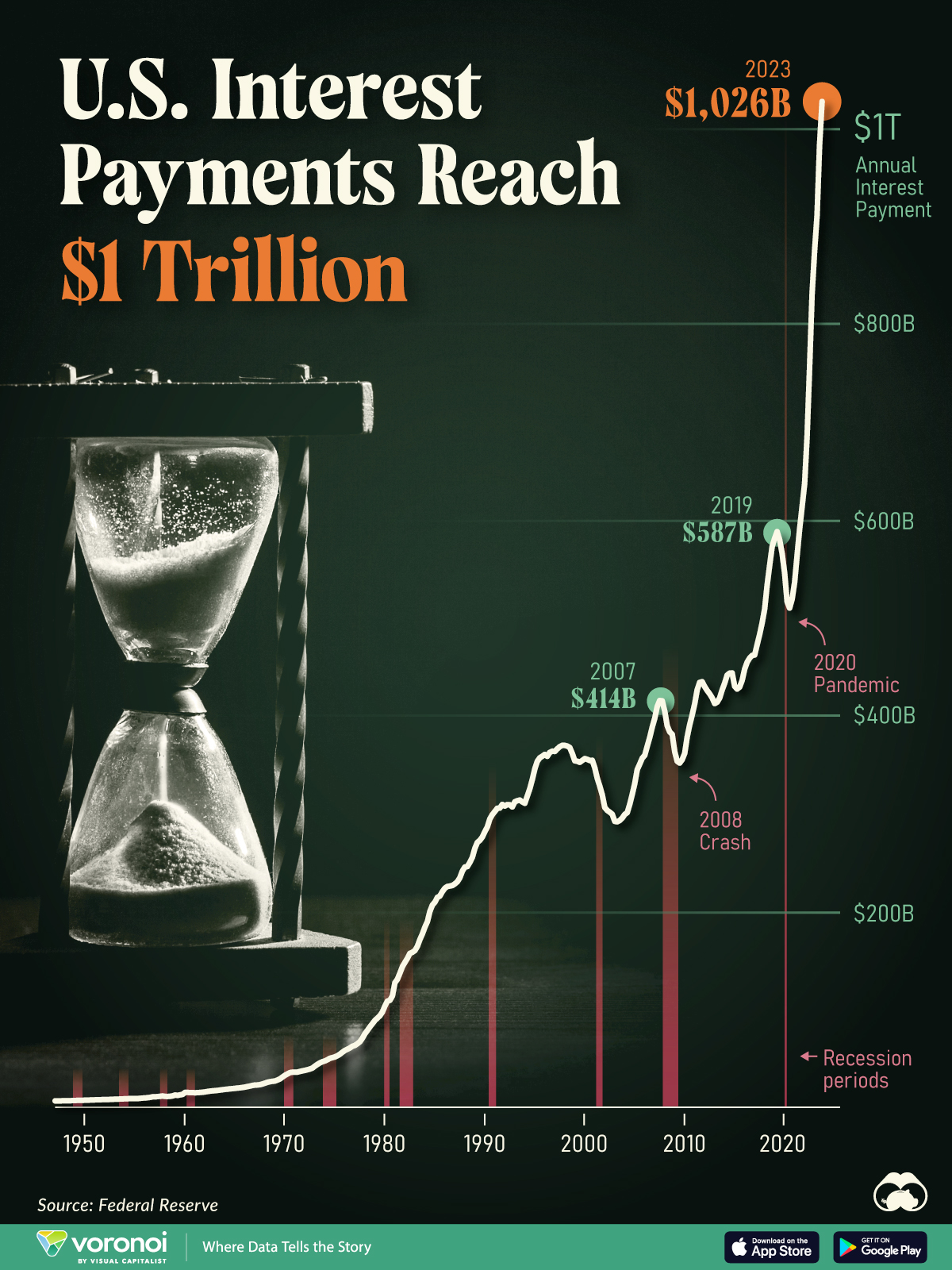

U.S. debt interest payments have surged past the $1 trillion dollar mark, amid high interest rates and an ever-expanding debt burden.

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

The cost of paying for America’s national debt crossed the $1 trillion dollar mark in 2023, driven by high interest rates and a record $34 trillion mountain of debt.

Over the last decade, U.S. debt interest payments have more than doubled amid vast government spending during the pandemic crisis. As debt payments continue to soar, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that debt servicing costs surpassed defense spending for the first time ever this year.

This graphic shows the sharp rise in U.S. debt payments, based on data from the Federal Reserve.

A $1 Trillion Interest Bill, and Growing

Below, we show how U.S. debt interest payments have risen at a faster pace than at another time in modern history:

| Date | Interest Payments | U.S. National Debt |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $1.0T | $34.0T |

| 2022 | $830B | $31.4T |

| 2021 | $612B | $29.6T |

| 2020 | $518B | $27.7T |

| 2019 | $564B | $23.2T |

| 2018 | $571B | $22.0T |

| 2017 | $493B | $20.5T |

| 2016 | $460B | $20.0T |

| 2015 | $435B | $18.9T |

| 2014 | $442B | $18.1T |

| 2013 | $425B | $17.2T |

| 2012 | $417B | $16.4T |

| 2011 | $433B | $15.2T |

| 2010 | $400B | $14.0T |

| 2009 | $354B | $12.3T |

| 2008 | $380B | $10.7T |

| 2007 | $414B | $9.2T |

| 2006 | $387B | $8.7T |

| 2005 | $355B | $8.2T |

| 2004 | $318B | $7.6T |

| 2003 | $294B | $7.0T |

| 2002 | $298B | $6.4T |

| 2001 | $318B | $5.9T |

| 2000 | $353B | $5.7T |

| 1999 | $353B | $5.8T |

| 1998 | $360B | $5.6T |

| 1997 | $368B | $5.5T |

| 1996 | $362B | $5.3T |

| 1995 | $357B | $5.0T |

| 1994 | $334B | $4.8T |

| 1993 | $311B | $4.5T |

| 1992 | $306B | $4.2T |

| 1991 | $308B | $3.8T |

| 1990 | $298B | $3.4T |

| 1989 | $275B | $3.0T |

| 1988 | $254B | $2.7T |

| 1987 | $240B | $2.4T |

| 1986 | $225B | $2.2T |

| 1985 | $219B | $1.9T |

| 1984 | $205B | $1.7T |

| 1983 | $176B | $1.4T |

| 1982 | $157B | $1.2T |

| 1981 | $142B | $1.0T |

| 1980 | $113B | $930.2B |

| 1979 | $96B | $845.1B |

| 1978 | $84B | $789.2B |

| 1977 | $69B | $718.9B |

| 1976 | $61B | $653.5B |

| 1975 | $55B | $576.6B |

| 1974 | $50B | $492.7B |

| 1973 | $45B | $469.1B |

| 1972 | $39B | $448.5B |

| 1971 | $36B | $424.1B |

| 1970 | $35B | $389.2B |

| 1969 | $30B | $368.2B |

| 1968 | $25B | $358.0B |

| 1967 | $23B | $344.7B |

| 1966 | $21B | $329.3B |

Interest payments represent seasonally adjusted annual rate at the end of Q4.

At current rates, the U.S. national debt is growing by a remarkable $1 trillion about every 100 days, equal to roughly $3.6 trillion per year.

As the national debt has ballooned, debt payments even exceeded Medicaid outlays in 2023—one of the government’s largest expenditures. On average, the U.S. spent more than $2 billion per day on interest costs last year. Going further, the U.S. government is projected to spend a historic $12.4 trillion on interest payments over the next decade, averaging about $37,100 per American.

Exacerbating matters is that the U.S. is running a steep deficit, which stood at $1.1 trillion for the first six months of fiscal 2024. This has accelerated due to the 43% increase in debt servicing costs along with a $31 billion dollar increase in defense spending from a year earlier. Additionally, a $30 billion increase in funding for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in light of the regional banking crisis last year was a major contributor to the deficit increase.

Overall, the CBO forecasts that roughly 75% of the federal deficit’s increase will be due to interest costs by 2034.

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoRanked: The Largest U.S. Corporations by Number of Employees

-

Green3 weeks ago

Green3 weeks agoRanked: Top Countries by Total Forest Loss Since 2001

-

Money2 weeks ago

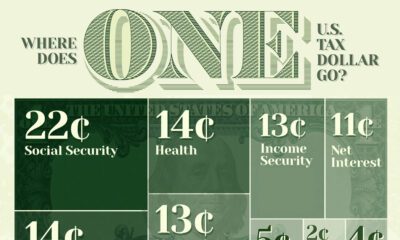

Money2 weeks agoWhere Does One U.S. Tax Dollar Go?

-

Automotive2 weeks ago

Automotive2 weeks agoAlmost Every EV Stock is Down After Q1 2024

-

AI2 weeks ago

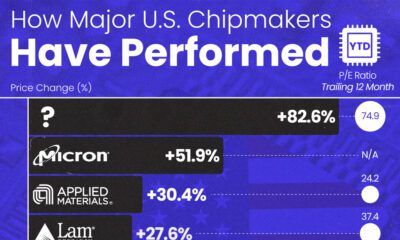

AI2 weeks agoThe Stock Performance of U.S. Chipmakers So Far in 2024

-

Markets2 weeks ago

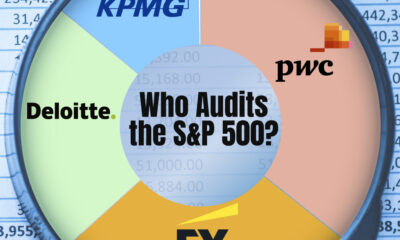

Markets2 weeks agoCharted: Big Four Market Share by S&P 500 Audits

-

Real Estate2 weeks ago

Real Estate2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?