Markets

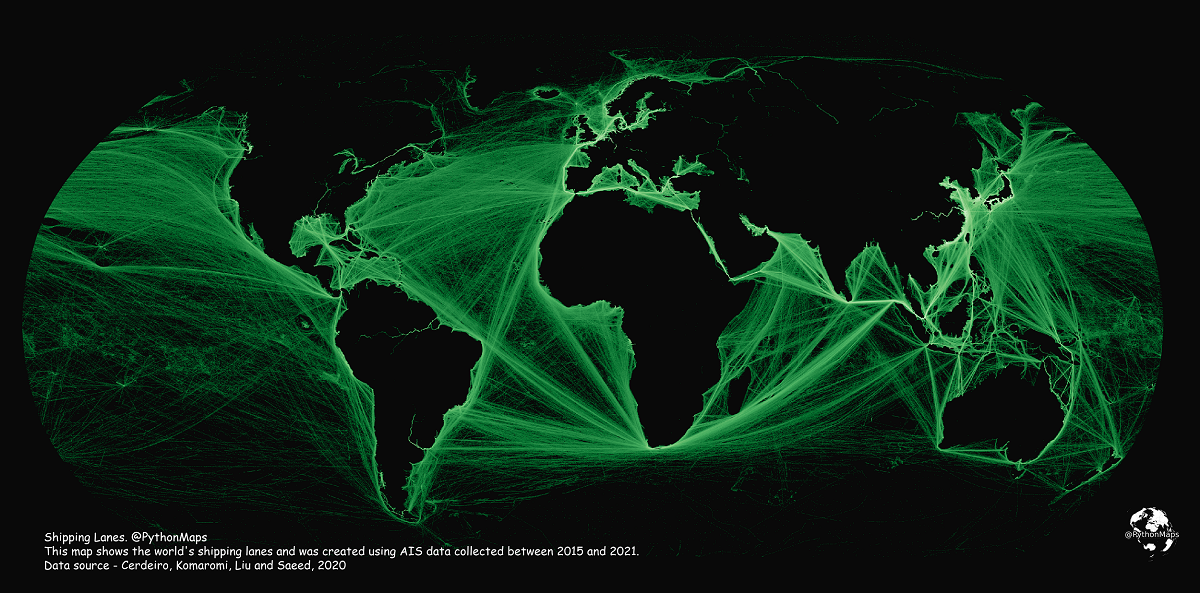

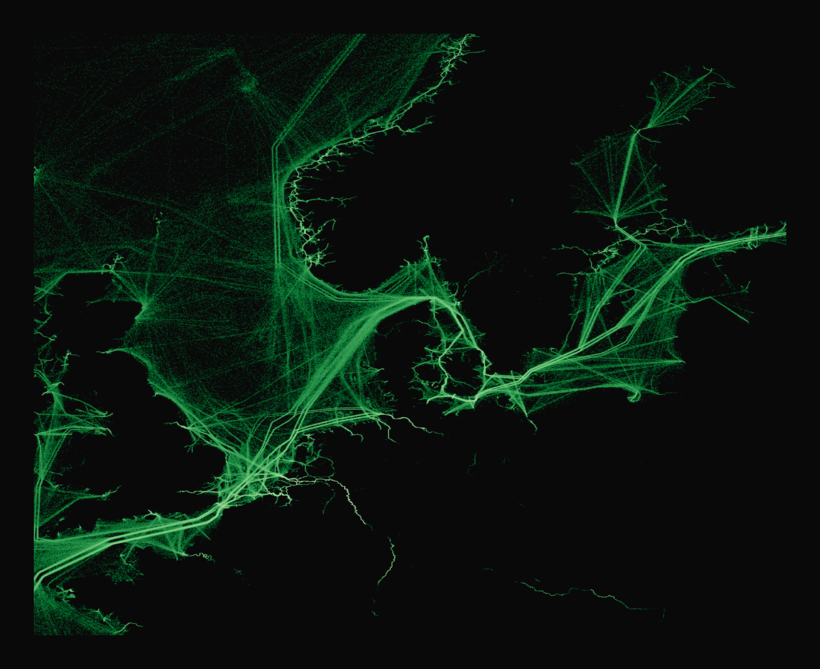

Mapping Shipping Lanes: Maritime Traffic Around the World

Click to view a larger version of the map.

Mapping Shipping Lanes: Maritime Traffic Around the World

Each year, thousands of ships travel across the globe, transporting everything from passengers to consumer goods like wheat and oil.

But just how busy are global maritime routes, and where are the world’s major shipping lanes? This map by Adam Symington paints a macro picture of the world’s maritime traffic by highlighting marine traffic density around the world.

It uses data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in partnership with The World Bank, as part of IMF’s World Seaborne Trade Monitoring System.

Data spans from Jan 2015 to Feb 2021 and includes five different types of ships: commercial ships, fishing ships, oil & gas, passenger ships, and leisure vessels.

An Overview of Key Maritime Shipping Lanes

If you take a look at the map, you’ll spot some distinct areas where traffic is heavily concentrated.

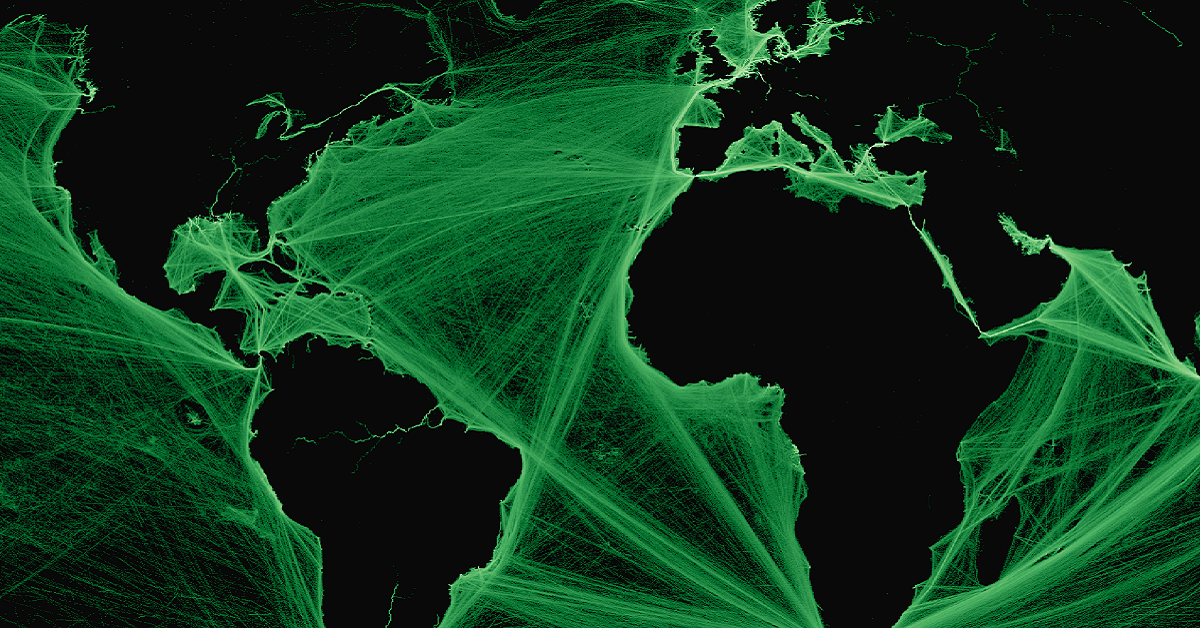

These high-density areas are the world’s main shipping lanes. Syminton provided some zoomed-in visuals of these waterways in detail, so let’s dive in:

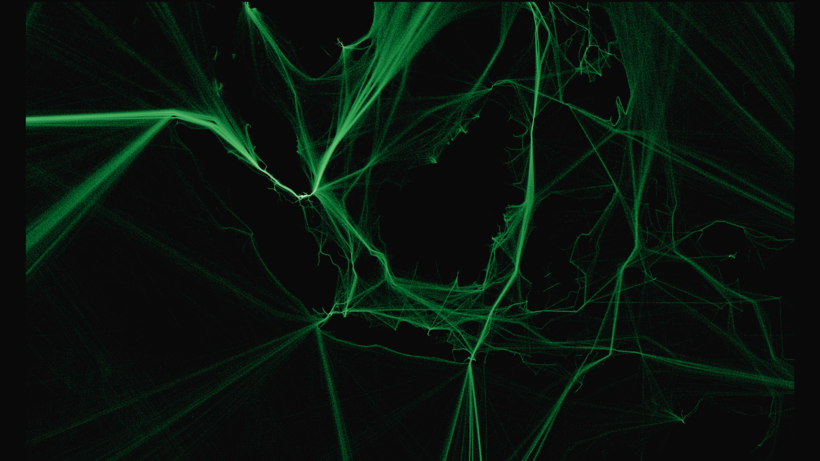

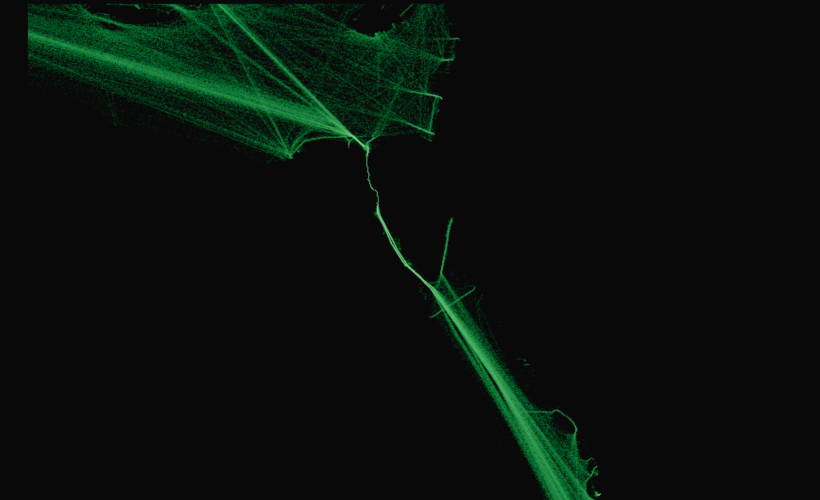

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a man-made waterway that connects the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. For ships traveling from the east to west coast of the U.S., this route avoids the far more treacherous Cape Horn at the tip of South America or the Bering Strait in the Arctic, and shaves off roughly 8,000 nautical miles—or 21 days off their journey.

In 2021, approximately 516.7 million tons of goods passed through the major waterway, according to Ricaurte Vasquez, the Panama Canal Authority’s administrator.

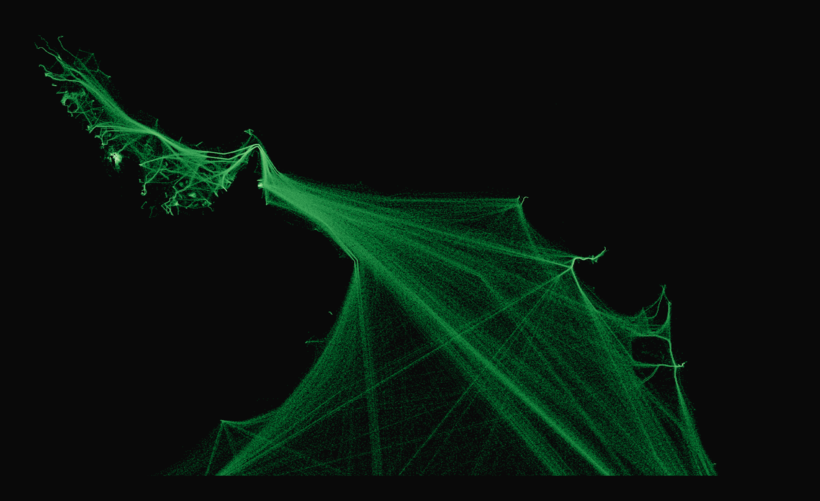

Strait of Malacca

This marine passage is the fastest connector between the Pacific and Indian oceans, winding through the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra. It’s a slender waterway—at its narrowest point, the canal is less than 1.9 miles wide. Approximately 70,000 ships pass through this strait each year.

The Danish Straits

Connecting the North Sea with the Baltic Sea, the Danish Straits include three channels: the Oresund, the Great Belt and the Little Belt.

The Danish Straits are known to be a major passageway for Russian oil exports—which, despite sanctions and boycotts against Russian oil, have remained strong throughout 2022 so far.

Suez Canal

This 120-mile-long artificial waterway runs through Egypt and connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, saving ships traveling between Asia and Europe a long passage around Africa. Over 20,600 vessels traveled through the canal in 2021.

Last year, the canal made headlines after a 1,312-foot-long container ship called the Ever Given got stuck in the canal for six days, causing a massive traffic jam and halting billions of dollars worth of traded goods.

Strait of Hormuz

This 615-mile waterway connects the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman and ultimately drains into the Arabian Sea. In 2020, the canal transported approximately 18 million barrels of oil every day.

The English Channel

Located between England and France, the 350-mile-long English Channel links the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. Approximately 500 vessels travel through the channel each day, making it one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Some of the major European rivers are also clearly visible in these visualizations, including the Thames in the UK, the Seine in France, and the Meuse (or Mass) that flows through Belgium and the Netherlands.

COVID-19’s Impact on Maritime Transport

Though these maps show six years worth of marine traffic, it’s important to remember that many sectors were negatively impacted by the global pandemic, and maritime trade was no exception. In 2020, global maritime shipments dropped by 3.8% to 10.65 billion tons.

While the drop wasn’t as severe as expected, and output is projected to keep growing throughout 2022, certain areas are still feeling the effects of COVID-19-induced restrictions.

For instance, in March 2022, shipping volume at the port of Shanghai screeched to a halt due to strict lockdowns in Shanghai, triggered by a COVID-19 outbreak. Traffic was impacted for months, and while operations have rebounded, marine traffic in the area is still congested.

This article was published as a part of Visual Capitalist's Creator Program, which features data-driven visuals from some of our favorite Creators around the world.

Economy

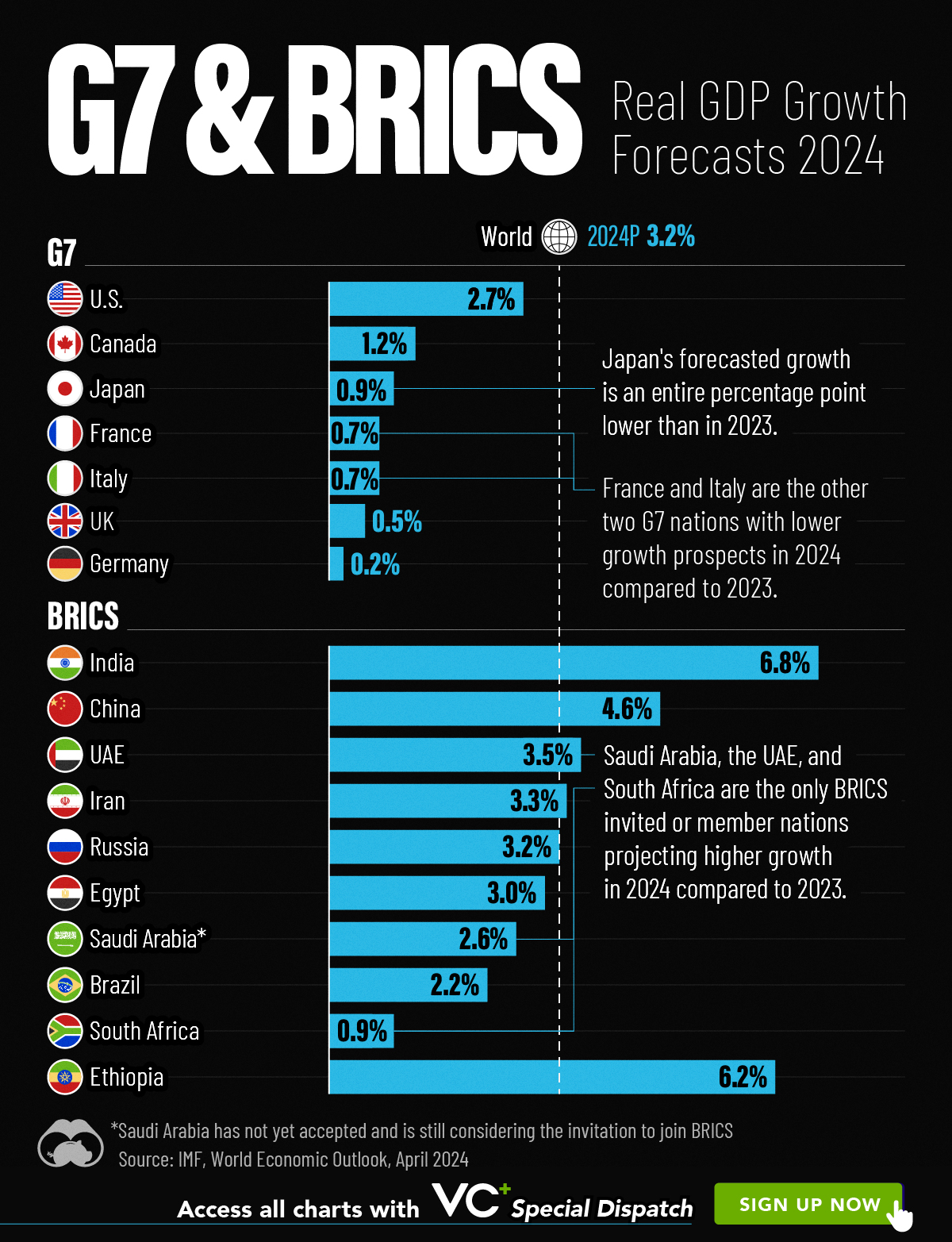

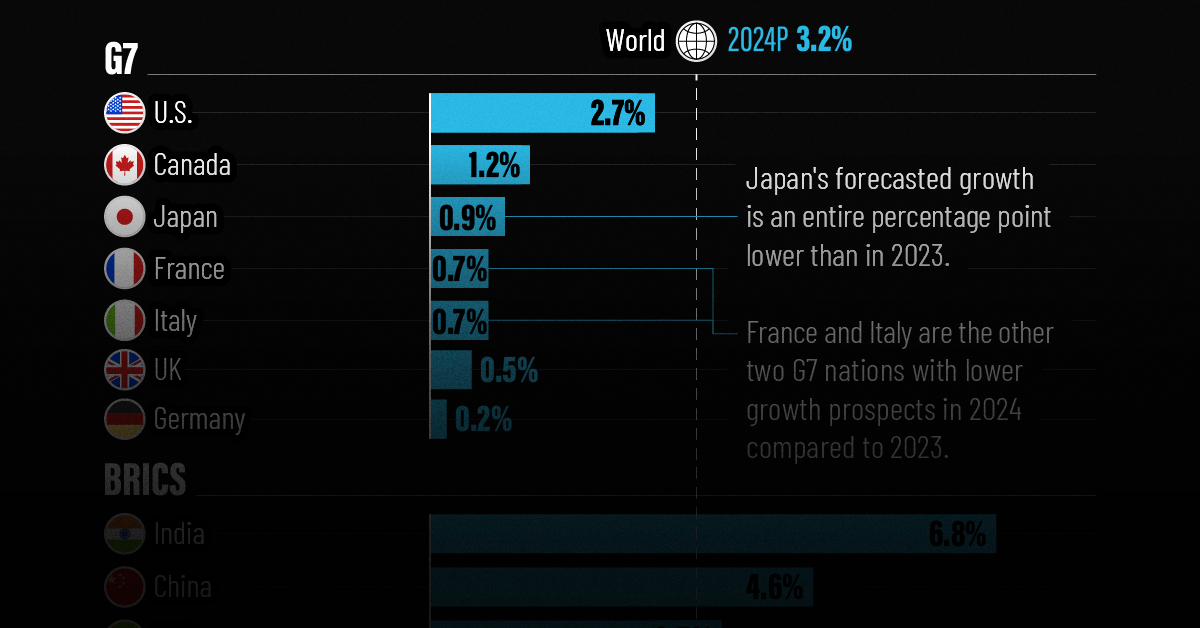

Economic Growth Forecasts for G7 and BRICS Countries in 2024

The IMF has released its economic growth forecasts for 2024. How do the G7 and BRICS countries compare?

G7 & BRICS Real GDP Growth Forecasts for 2024

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) has released its real gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecasts for 2024, and while global growth is projected to stay steady at 3.2%, various major nations are seeing declining forecasts.

This chart visualizes the 2024 real GDP growth forecasts using data from the IMF’s 2024 World Economic Outlook for G7 and BRICS member nations along with Saudi Arabia, which is still considering an invitation to join the bloc.

Get the Key Insights of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

Want a visual breakdown of the insights from the IMF’s 2024 World Economic Outlook report?

This visual is part of a special dispatch of the key takeaways exclusively for VC+ members.

Get the full dispatch of charts by signing up to VC+.

Mixed Economic Growth Prospects for Major Nations in 2024

Economic growth projections by the IMF for major nations are mixed, with the majority of G7 and BRICS countries forecasted to have slower growth in 2024 compared to 2023.

Only three BRICS-invited or member countries, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and South Africa, have higher projected real GDP growth rates in 2024 than last year.

| Group | Country | Real GDP Growth (2023) | Real GDP Growth (2024P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G7 | 🇺🇸 U.S. | 2.5% | 2.7% |

| G7 | 🇨🇦 Canada | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| G7 | 🇯🇵 Japan | 1.9% | 0.9% |

| G7 | 🇫🇷 France | 0.9% | 0.7% |

| G7 | 🇮🇹 Italy | 0.9% | 0.7% |

| G7 | 🇬🇧 UK | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| G7 | 🇩🇪 Germany | -0.3% | 0.2% |

| BRICS | 🇮🇳 India | 7.8% | 6.8% |

| BRICS | 🇨🇳 China | 5.2% | 4.6% |

| BRICS | 🇦🇪 UAE | 3.4% | 3.5% |

| BRICS | 🇮🇷 Iran | 4.7% | 3.3% |

| BRICS | 🇷🇺 Russia | 3.6% | 3.2% |

| BRICS | 🇪🇬 Egypt | 3.8% | 3.0% |

| BRICS-invited | 🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia | -0.8% | 2.6% |

| BRICS | 🇧🇷 Brazil | 2.9% | 2.2% |

| BRICS | 🇿🇦 South Africa | 0.6% | 0.9% |

| BRICS | 🇪🇹 Ethiopia | 7.2% | 6.2% |

| 🌍 World | 3.2% | 3.2% |

China and India are forecasted to maintain relatively high growth rates in 2024 at 4.6% and 6.8% respectively, but compared to the previous year, China is growing 0.6 percentage points slower while India is an entire percentage point slower.

On the other hand, four G7 nations are set to grow faster than last year, which includes Germany making its comeback from its negative real GDP growth of -0.3% in 2023.

Faster Growth for BRICS than G7 Nations

Despite mostly lower growth forecasts in 2024 compared to 2023, BRICS nations still have a significantly higher average growth forecast at 3.6% compared to the G7 average of 1%.

While the G7 countries’ combined GDP is around $15 trillion greater than the BRICS nations, with continued higher growth rates and the potential to add more members, BRICS looks likely to overtake the G7 in economic size within two decades.

BRICS Expansion Stutters Before October 2024 Summit

BRICS’ recent expansion has stuttered slightly, as Argentina’s newly-elected president Javier Milei declined its invitation and Saudi Arabia clarified that the country is still considering its invitation and has not joined BRICS yet.

Even with these initial growing pains, South Africa’s Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor told reporters in February that 34 different countries have submitted applications to join the growing BRICS bloc.

Any changes to the group are likely to be announced leading up to or at the 2024 BRICS summit which takes place October 22-24 in Kazan, Russia.

Get the Full Analysis of the IMF’s Outlook on VC+

This visual is part of an exclusive special dispatch for VC+ members which breaks down the key takeaways from the IMF’s 2024 World Economic Outlook.

For the full set of charts and analysis, sign up for VC+.

-

Mining1 week ago

Mining1 week agoGold vs. S&P 500: Which Has Grown More Over Five Years?

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Countries2 weeks ago

Countries2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoThe Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries