Money

The Big Mac Index: A Measure of Purchasing Power Parity & Burger Inflation

The Big Mac Index: A Measure of PPP and Burger Inflation

The Big Mac was created in 1967 by Jim Delligati, a McDonald’s franchise owner in Pennsylvania. It was launched throughout the U.S. the following year, and today you can buy one in more than 70 countries. However, the price you pay will vary based on where you are, as evidenced by the Big Mac Index.

Spanning from 2004-2022, this animation from James Eagle shows the U.S. dollar price of a Big Mac in select countries around the world.

What Does the Big Mac Index Show?

The Big Mac Index was invented by The Economist in 1986. It is intended to be a lighthearted way to demonstrate the concept of purchasing power parity. In other words, it helps illustrate the idea that market exchange rates between countries may be “out of whack” when compared to the cost of buying the same basket of goods and services in those places.

Given that McDonald’s is one of the biggest companies in the world and the Big Mac is widely available globally, it means that the famous burger can be used as a basic goods comparison between most countries. It also has the advantage of having the same inputs and distribution system, with a few minor modifications (like chicken patties in India instead of beef).

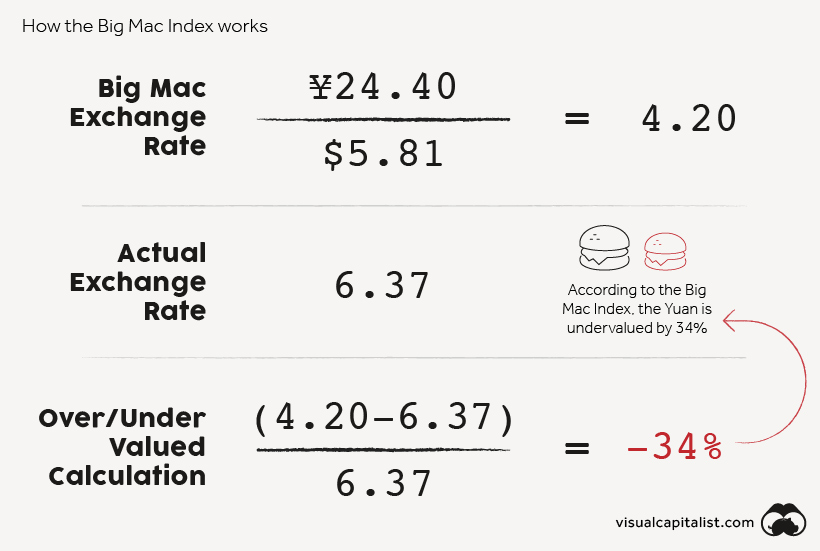

Using the price of a Big Mac in two countries, the index can give an indication as to whether a currency may be over or undervalued. For example, a Big Mac costs ¥24.40 in China and $5.81 in the United States. By comparing the implied exchange rate to the actual exchange rate, we can see whether the Yuan is over or undervalued.

According to the Big Mac Index, the Yuan is undervalued by 34%.

Beyond currency misalignment, the index has other uses. For instance, it shows inflation in burger prices over time. If we compare the price of a Big Mac across countries in the same currency—such as the U.S. dollar—we are also able to see where burgers are cheaper or relatively more expensive.

Burger Costs Around the World

In the animation, all Big Mac prices have been converted from local currency to U.S. dollars based on the actual exchange rate in effect at the time. Below, we show the change in price of a Big Mac in select countries, ordered by January 2022 prices.

| Country | May 2004 | January 2022 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | $4.88 | $6.98 | 43% |

| Norway | $5.18 | $6.39 | 23% |

| United States | $2.90 | $5.81 | 100% |

| Sweden | $3.94 | $5.79 | 47% |

| Israel | $2.79 | $5.35 | 92% |

| Canada | $2.33 | $5.32 | 129% |

| Venezuela | $1.48 | $5.06 | 243% |

| Euro area | $3.29 | $4.95 | 51% |

| Denmark | $4.46 | $4.82 | 8% |

| Britain | $3.37 | $4.82 | 43% |

| New Zealand | $2.65 | $4.60 | 73% |

| Australia | $2.27 | $4.51 | 98% |

| Singapore | $1.93 | $4.36 | 126% |

| Brazil | $1.70 | $4.31 | 154% |

| Argentina | $1.48 | $4.29 | 190% |

| Sri Lanka | $1.41 | $4.15 | 193% |

| Czech Republic | $2.13 | $4.11 | 93% |

| Chile | $2.18 | $3.88 | 78% |

| Thailand | $1.45 | $3.84 | 166% |

| China | $1.26 | $3.83 | 205% |

| South Korea | $2.72 | $3.82 | 40% |

| Poland | $1.63 | $3.44 | 111% |

| Japan | $2.32 | $3.38 | 46% |

| Peru | $2.58 | $3.36 | 31% |

| Mexico | $2.07 | $3.34 | 62% |

| Hungary | $2.51 | $3.09 | 23% |

| Hong Kong | $1.54 | $2.82 | 83% |

| Philippines | $1.23 | $2.79 | 126% |

| Taiwan | $2.25 | $2.70 | 20% |

| South Africa | $1.86 | $2.58 | 39% |

| Ukraine | $1.36 | $2.43 | 79% |

| Malaysia | $1.33 | $2.39 | 80% |

| Indonesia | $1.77 | $2.36 | 34% |

| Turkey | $2.58 | $1.86 | -28% |

| Russia | $1.45 | $1.74 | 20% |

Switzerland takes the cake for the priciest Big Mac, followed closely behind by Norway. Both countries have relatively high price levels but also enjoy higher wages when compared to other OECD countries.

Venezuela has seen the largest jump in burger prices, with the cost of a Big Mac climbing nearly 250% since 2004. The country has been plagued by hyperinflation for years, so it’s no surprise to see large price swings in the country’s data.

While it appears that the price of a Big Mac has decreased in Turkey, this is because the prices are shown in U.S. dollars. The new Turkish lira has depreciated against the U.S. dollar more than 90% since it was introduced in 2005.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Russia has the cheapest Big Mac, reflecting the country’s lower price levels. Labor costs in Russia are roughly a third of those in Switzerland.

The Limitations of Burgernomics

The Big Mac Index is useful for a number of reasons. Investors can use it to measure inflation over time, and compare this to official records. This can help them value bonds and other securities that are sensitive to inflation. The Big Mac Index also indicates whether a currency may be over or undervalued, and investors can place foreign exchange trades accordingly.

Of course, the index does have shortcomings. Here are some that economists have noted.

- Non-traded services can have different prices across countries. The price of a Big Mac will be influenced by the costs of things like labor, but this is not a reflection of relative currency values. The Economist now releases a GDP-adjusted version of the Big Mac Index to help address this criticism.

- McDonald’s is not in every country in the world. This means the geographic reach of the Big Mac Index has some limitations, particularly in Africa.

- The index lacks diversity. The index is made up of one item: the Big Mac. Because of this, it lacks the diversity of other economic metrics such as the Consumer Price Index.

Despite all of these limitations, the Big Mac Index does act as a good starting place for understanding purchasing power parity. Through the simplicity of burgers, complex economic theory is easier to digest.

This article was published as a part of Visual Capitalist's Creator Program, which features data-driven visuals from some of our favorite Creators around the world.

Demographics

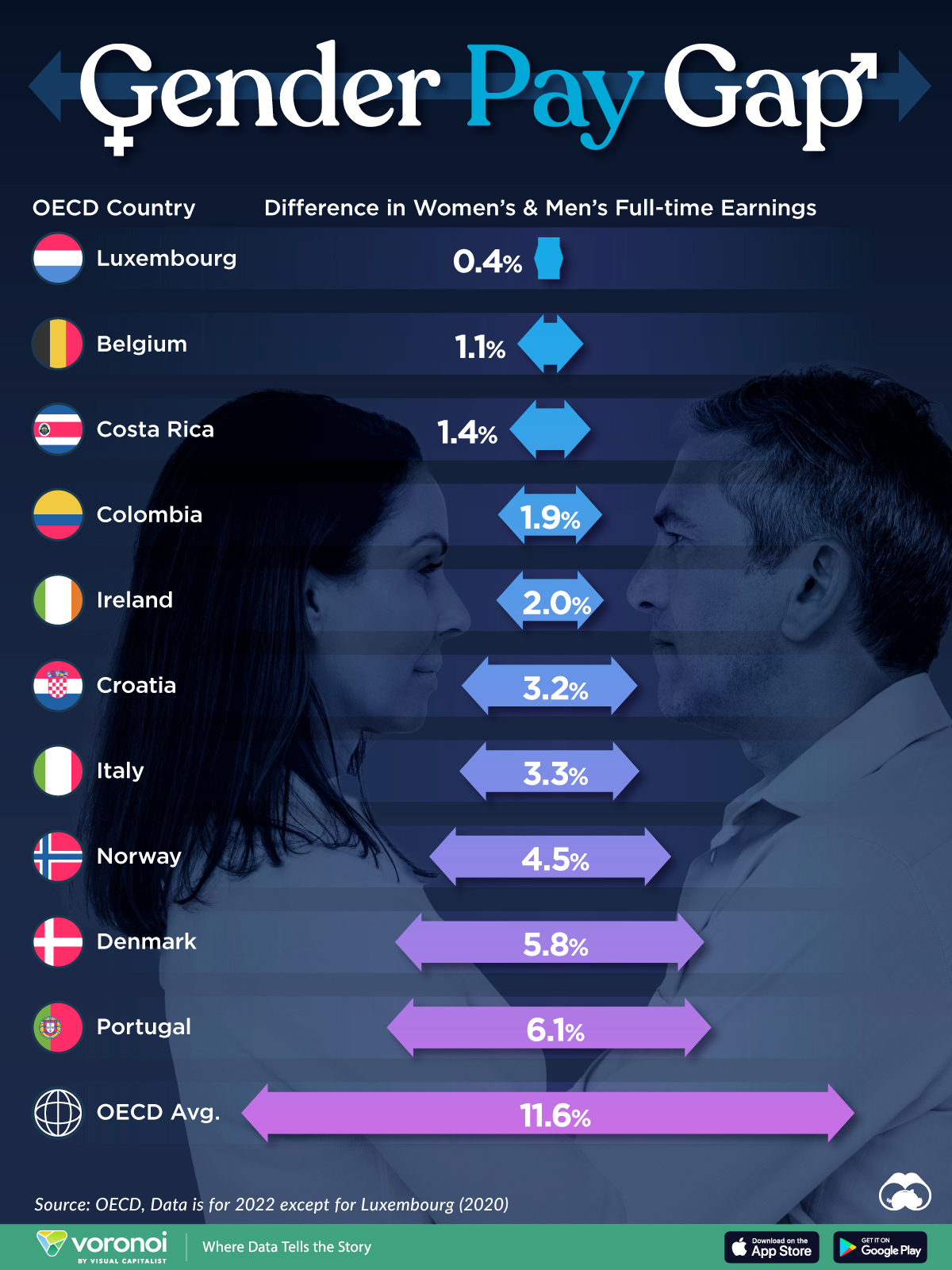

The Smallest Gender Wage Gaps in OECD Countries

Which OECD countries have the smallest gender wage gaps? We look at the 10 countries with gaps lower than the average.

The Smallest Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Among the 38 member countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), several have made significant strides in addressing income inequality between men and women.

In this graphic we’ve ranked the OECD countries with the 10 smallest gender pay gaps, using the latest data from the OECD for 2022.

The gender pay gap is calculated as the difference between median full-time earnings for men and women divided by the median full-time earnings of men.

Which Countries Have the Smallest Gender Pay Gaps?

Luxembourg’s gender pay gap is the lowest among OECD members at only 0.4%—well below the OECD average of 11.6%.

| Rank | Country | Percentage Difference in Men's & Women's Full-time Earnings |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 🇱🇺 Luxembourg | 0.4% |

| 2 | 🇧🇪 Belgium | 1.1% |

| 3 | 🇨🇷 Costa Rica | 1.4% |

| 4 | 🇨🇴 Colombia | 1.9% |

| 5 | 🇮🇪 Ireland | 2.0% |

| 6 | 🇭🇷 Croatia | 3.2% |

| 7 | 🇮🇹 Italy | 3.3% |

| 8 | 🇳🇴 Norway | 4.5% |

| 9 | 🇩🇰 Denmark | 5.8% |

| 10 | 🇵🇹 Portugal | 6.1% |

| OECD Average | 11.6% |

Notably, eight of the top 10 countries with the smallest gender pay gaps are located in Europe, as labor equality laws designed to target gender differences have begun to pay off.

The two other countries that made the list were Costa Rica (1.4%) and Colombia (1.9%), which came in third and fourth place, respectively.

How Did Luxembourg (Nearly) Eliminate its Gender Wage Gap?

Luxembourg’s virtually-non-existent gender wage gap in 2020 can be traced back to its diligent efforts to prioritize equal pay. Since 2016, firms that have not complied with the Labor Code’s equal pay laws have been subjected to penalizing fines ranging from €251 to €25,000.

Higher female education rates also contribute to the diminishing pay gap, with Luxembourg tied for first in the educational attainment rankings of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index Report for 2023.

See More Graphics about Demographics and Money

While these 10 countries are well below the OECD’s average gender pay gap of 11.6%, many OECD member countries including the U.S. are significantly above the average. To see the full list of the top 10 OECD countries with the largest gender pay gaps, check out this visualization.

-

Mining2 weeks ago

Mining2 weeks agoCharted: The Value Gap Between the Gold Price and Gold Miners

-

Real Estate1 week ago

Real Estate1 week agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoCharted: Big Four Market Share by S&P 500 Audits

-

AI1 week ago

AI1 week agoThe Stock Performance of U.S. Chipmakers So Far in 2024

-

Misc1 week ago

Misc1 week agoAlmost Every EV Stock is Down After Q1 2024

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhere Does One U.S. Tax Dollar Go?

-

Green2 weeks ago

Green2 weeks agoRanked: Top Countries by Total Forest Loss Since 2001

-

Real Estate2 weeks ago

Real Estate2 weeks agoVisualizing America’s Shortage of Affordable Homes