Misc

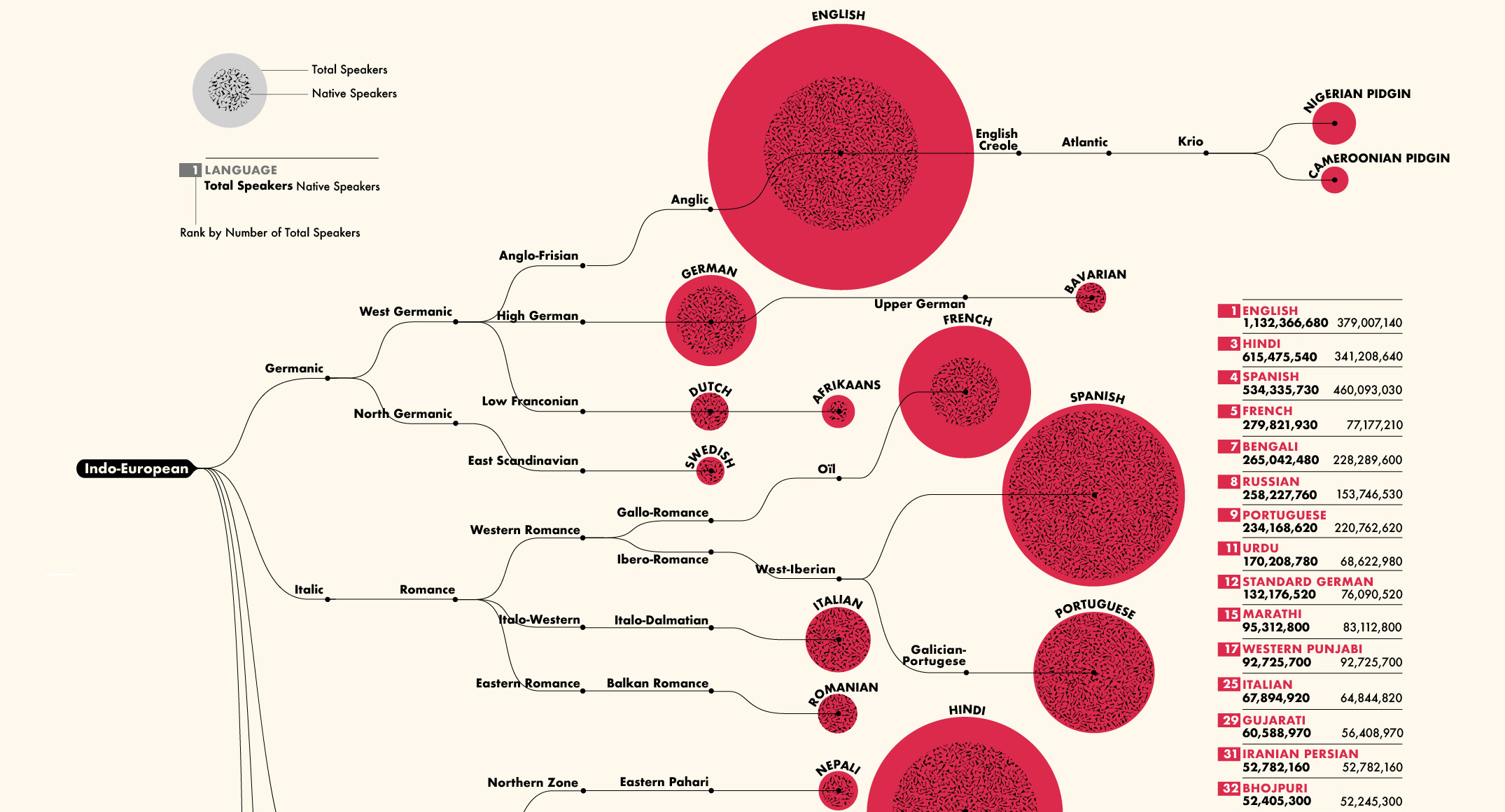

Ranked: The 100 Most Spoken Languages Around the World

Ranked: The 100 Most Spoken Languages Worldwide

Even though you’re reading this article in English, there’s a good chance it might not be your mother tongue. Of the billion-strong English speakers in the world, only 33% consider it their native language.

The popularity of a language depends greatly on utility and geographic location. Additionally, how we measure the spread of world languages can vary greatly depending on whether you look at total speakers or native speakers.

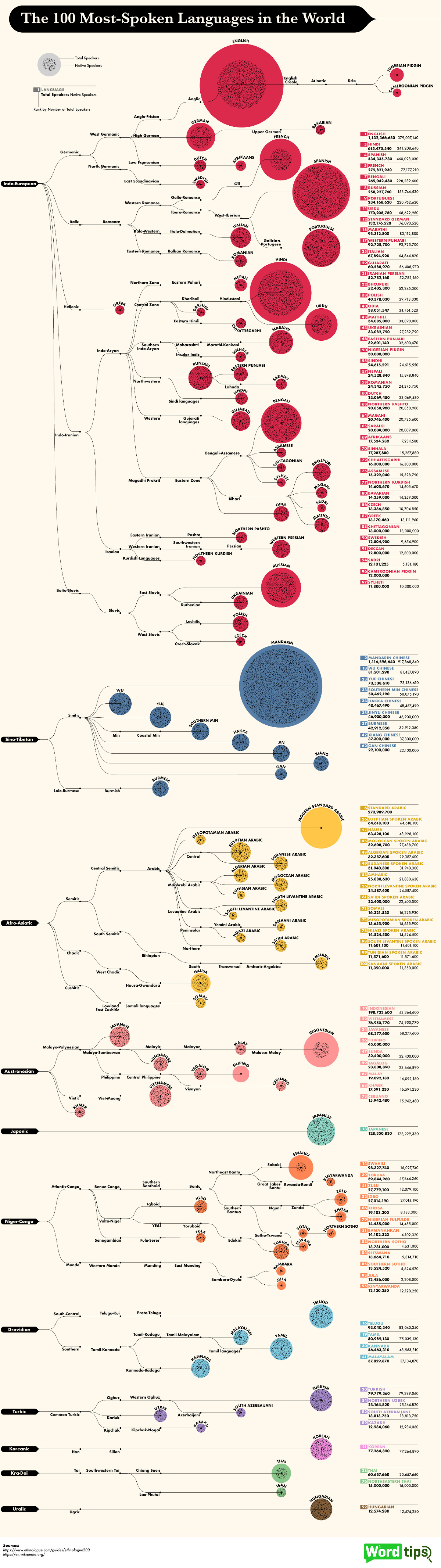

Today’s detailed visualization from WordTips illustrates the 100 most spoken languages in the world, the number of native speakers for each language, and the origin tree that each language has branched out from.

How Do You Define A Language?

The data comes from the 22nd edition of Ethnologue, a database covering a majority of the world’s population, detailing approximately 7,111 living languages in existence today.

The definitions of languages are often dynamic, blurring the lines around a singular understanding of what makes a language:

- Linguistic: focused on lexical and grammatical differences, or on variations within speech communities

- Social: focused on cultural or political factors, as well as heritage and identity

For the purposes of measurement, the researchers use the ISO 693-3 set of criteria, which accounts for related varieties and dialects—ensuring that linguistics are not the only factor considered in this count of languages.

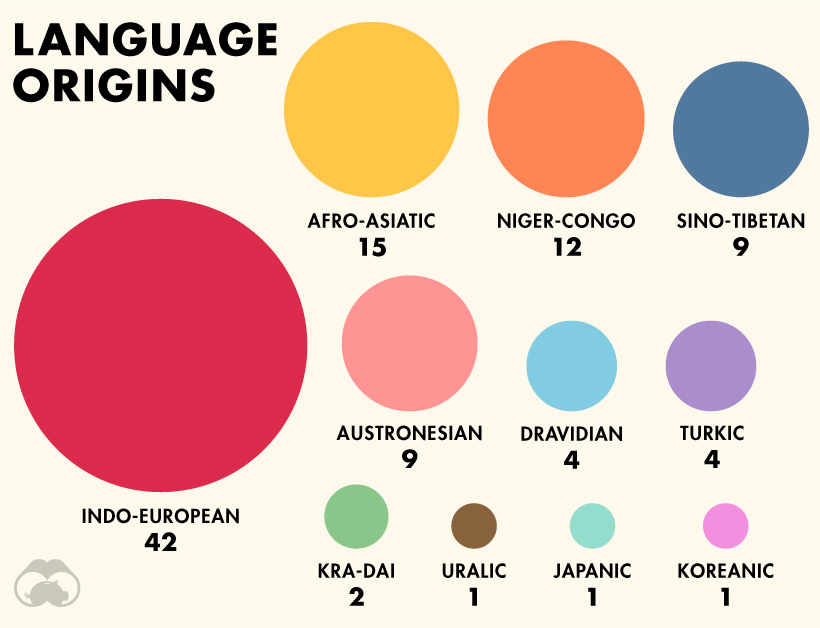

Here are the language origins of the 100 most spoken languages:

Indo-European languages have the widest spread worldwide. According to Ethnologue, the language family contains over 3 billion speakers in total. Interestingly, there are actually 1,526 Niger-Congo languages altogether, though only 12 are represented here.

Let’s now dive into the top 10 most spoken languages overall.

Which Languages Have the Most Speakers?

It comes as no surprise that English reigns supreme, with over 1.1 billion total speakers—or roughly 15% of the global population. Mandarin Chinese, Hindi, Spanish, and French round out the top five.

| Rank | Language | Total Speakers | Language Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | English | 1,132 million | Indo-European |

| 2 | Mandarin Chinese | 1,117 million | Sino-Tibetan |

| 3 | Hindi | 615 million | Indo-European |

| 4 | Spanish | 534 million | Indo-European |

| 5 | French | 280 million | Indo-European |

| 6 | Standard Arabic | 274 million | Afro-Asiatic |

| 7 | Bengali | 265 million | Indo-European |

| 8 | Russian | 258 million | Indo-European |

| 9 | Portuguese | 234 million | Indo-European |

| 10 | Indonesian | 199 million | Austronesian |

However, this is only one piece in the full fabric of languages.

The metrics for native speakers tell a slightly different tale, as Mandarin Chinese shoots up to 918 million—almost 2.5x that of English native speakers.

| Rank | Language | Native Speakers | Language Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mandarin Chinese | 918 million | Sino-Tibetan |

| 2 | Spanish | 460 million | Indo-European |

| 3 | English | 379 million | Indo-European |

| 4 | Hindi | 341 million | Indo-European |

| 5 | Bengali | 228 million | Indo-European |

| 6 | Portuguese | 221 million | Indo-European |

| 7 | Russian | 154 million | Indo-European |

| 8 | Japanese | 128 million | Japanic |

| 9 | Western Punjabi | 93 million | Indo-European |

| 10 | Marathi | 83 million | Indo-European |

Note: No native speaker data was available for Filipino, Standard Arabic, Nigerian Pidgin, or Cameroonian Pidgin.

Here, Spanish comes in strong second for native speakers with 460 million, considering it’s well-used across Latin America. The Indian languages of Hindi and Bengali cap off the top five by native speakers as well.

These are the biggest languages people learn growing up, but what about the ones they pick up later in life?

What About Second (L2) Languages?

Nearly 43% of the world’s population is bilingual, with the ability to switch between two languages with ease.

From the data, second language (L2) speakers can be calculated by looking at the difference between native and total speakers, as a proportion of the total. For example, 66% of English speakers learned it as a second language.

Swahili surprisingly has the highest ratio of L2 speakers to total speakers—although it only has 16 million native speakers, this shoots up to 98 million total speakers. Overall, 82% of Swahili speakers know it as a second language.

Swahili is listed as a national or official language in several African countries: Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. It’s likely that the movement of people from rural areas into big cities in search of better economic opportunities, is what’s boosting the adoption of Swahili as a second language.

Indonesian is another similar example. With a 78% proportion of L2 speakers compared to total speakers, this variation on the Malay language has been used as the lingua franca across the islands for a long time. In contrast, only 17% of Mandarin speakers know it as a second language, perhaps because it is one of the most challenging languages to learn.

Keeping Language Traditions Alive

Languages are fluid, and constantly evolving—altogether, the 100 most spoken languages paint a unique picture across centuries of a changing world. Here’s the full list of these languages, by types of speakers and language origin.

| Rank | Language | Total Speakers | Native Speakers | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | English | 1,132M | 379M | Indo-European |

| 2 | Mandarin Chinese | 1,117M | 918M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 3 | Hindi | 615M | 341M | Indo-European |

| 4 | Spanish | 534M | 460M | Indo-European |

| 5 | French | 280M | 77M | Indo-European |

| 6 | Standard Arabic | 274M | NA | Afro-Asiatic |

| 7 | Bengali | 265M | 228M | Indo-European |

| 8 | Russian | 258M | 154M | Indo-European |

| 9 | Portuguese | 234M | 221M | Indo-European |

| 10 | Indonesian | 199M | 43M | Austronesian |

| 11 | Urdu | 170M | 69M | Indo-European |

| 12 | Standard German | 132M | 76M | Indo-European |

| 13 | Japanese | 128M | 128M | Japanic |

| 14 | Swahili | 98M | 16M | Niger-Congo |

| 15 | Marathi | 95M | 83M | Indo-European |

| 16 | Telugu | 93M | 82M | Dravidian |

| 17 | Western Punjabi | 93M | 93M | Indo-European |

| 18 | Wu Chinese | 82M | 81M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 19 | Tamil | 81M | 75M | Dravidian |

| 20 | Turkish | 80M | 69M | Turkic |

| 21 | Korean | 77M | 77M | Koreanic |

| 22 | Vietnamese | 77M | 76M | Austronesian |

| 23 | Yue Chinese | 74M | 73M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 24 | Javanese | 68M | 68M | Austronesian |

| 25 | Italian | 68M | 65M | Indo-European |

| 26 | Egyptian Spoken Arabic | 65M | 65M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 27 | Hausa | 63M | 44M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 28 | Thai | 61M | 21M | Kra-Dai |

| 29 | Gujarati | 61M | 56M | Indo-European |

| 30 | Kannada | 56M | 44M | Dravidian |

| 31 | Iranian Persian | 53M | 53M | Indo-European |

| 32 | Bhojpuri | 52M | 52M | Indo-European |

| 33 | Southern Min Chinese | 50M | 50M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 34 | Hakka Chinese | 48M | 48M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 35 | Jinyu Chinese | 47M | 47M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 36 | Filipino | 45M | NA | Austronesian |

| 37 | Burmese | 43M | 33M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 38 | Polish | 40M | 40M | Indo-European |

| 39 | Yoruba | 40M | 38M | Niger-Congo |

| 40 | Odia | 38M | 34M | Indo-European |

| 41 | Malayalam | 38M | 37M | Dravidian |

| 42 | Xiang Chinese | 37M | 37M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 43 | Maithili | 34M | 34M | Indo-European |

| 44 | Ukrainian | 33M | 27M | Indo-European |

| 45 | Moroccan Spoken Arabic | 33M | 27M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 46 | Eastern Punjabi | 33M | 33M | Indo-European |

| 47 | Sunda | 32M | 32M | Austronesian |

| 48 | Algerian Spoken Arabic | 32M | 29M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 49 | Sudanese Spoken Arabic | 32M | 32M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 50 | Nigerian Pidgin | 30M | NA | Indo-European |

| 51 | Zulu | 28M | 12M | Niger-Congo |

| 52 | Igbo | 27M | 27M | Niger-Congo |

| 53 | Amharic | 26M | 22M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 54 | Northern Uzbek | 25M | 25M | Turkic |

| 55 | Sindhi | 25M | 25M | Indo-European |

| 56 | North Levantine Spoken Arabic | 25M | 25M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 57 | Nepali | 25M | 16M | Indo-European |

| 58 | Romanian | 24M | 24M | Indo-European |

| 59 | Tagalog | 24M | 24M | Austronesian |

| 60 | Dutch | 23M | 23M | Indo-European |

| 61 | Sa'idi Spoken Arabic | 22M | 22M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 62 | Gan Chinese | 22M | 22M | Sino-Tibetan |

| 63 | Northern Pashto | 21M | 21M | Indo-European |

| 64 | Magahi | 21M | 21M | Indo-European |

| 65 | Saraiki | 20M | 20M | Indo-European |

| 66 | Xhosa | 19M | 8M | Niger-Congo |

| 67 | Malay | 19M | 16M | Austronesian |

| 68 | Khmer | 18M | 17M | Austronesian |

| 69 | Afrikaans | 18M | 7M | Indo-European |

| 70 | Sinhala | 17M | 15M | Indo-European |

| 71 | Somali | 16M | 16M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 72 | Chhattisgarhi | 16M | 16M | Indo-European |

| 73 | Cebuano | 16M | 16M | Austronesian |

| 74 | Mesopotamian Spoken Arabic | 16M | 16M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 75 | Assamese | 15M | 15M | Indo-European |

| 76 | Northeastern Thai | 15M | 15M | Kra-Dai |

| 77 | Northern Kurdish | 15M | 15M | Indo-European |

| 78 | Hijazi Spoken Arabic | 15M | 15M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 79 | Nigerian Fulfulde | 14M | 14M | Niger-Congo |

| 80 | Bavarian | 14M | 14M | Indo-European |

| 81 | Bamanankan | 14M | 4M | Niger-Congo |

| 82 | South Azerbaijani | 14M | 14M | Turkic |

| 83 | Northern Sotho | 14M | 5M | Niger-Congo |

| 84 | Setswana | 14M | 6M | Niger-Congo |

| 85 | Souther Sotho | 14M | 6M | Niger-Congo |

| 86 | Czech | 13M | 11M | Indo-European |

| 87 | Greek | 13M | 13M | Indo-European |

| 88 | Chittagonian | 13M | 13M | Indo-European |

| 89 | Kazakh | 13M | 13M | Turkic |

| 90 | Swedish | 13M | 10M | Indo-European |

| 91 | Deccan | 13M | 13M | Indo-European |

| 92 | Hungarian | 13M | 13M | Uralic |

| 93 | Jula | 12M | 2M | Niger-Congo |

| 94 | Sadri | 12M | 5M | Indo-European |

| 95 | Kinyarwanda | 12M | 12M | Niger-Congo |

| 96 | Cameroonian Pidgin | 12M | NA | Indo-European |

| 97 | Sylheti | 12M | 10M | Indo-European |

| 98 | South Levantine Spoken Arabic | 12M | 12M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 99 | Tunisian Spoken Arabic | 12M | 12M | Afro-Asiatic |

| 100 | Sanaani Spoken Arabic | 11M | 11M | Afro-Asiatic |

One reason these languages are popular is that they are actively and consistently used. Unfortunately, nearly 3,000 (about 40%) of all languages are at risk of being lost, or are already in the process of dying out today.

Languages play a crucial role in our daily lives. … [Their] losses have huge negative impacts indigenous peoples’ most basic human rights.

—UN, IYoIL statement

As a result, the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IYoIL), with a resolution to continue fostering these languages and pass on their knowledge for future generations.

VC+

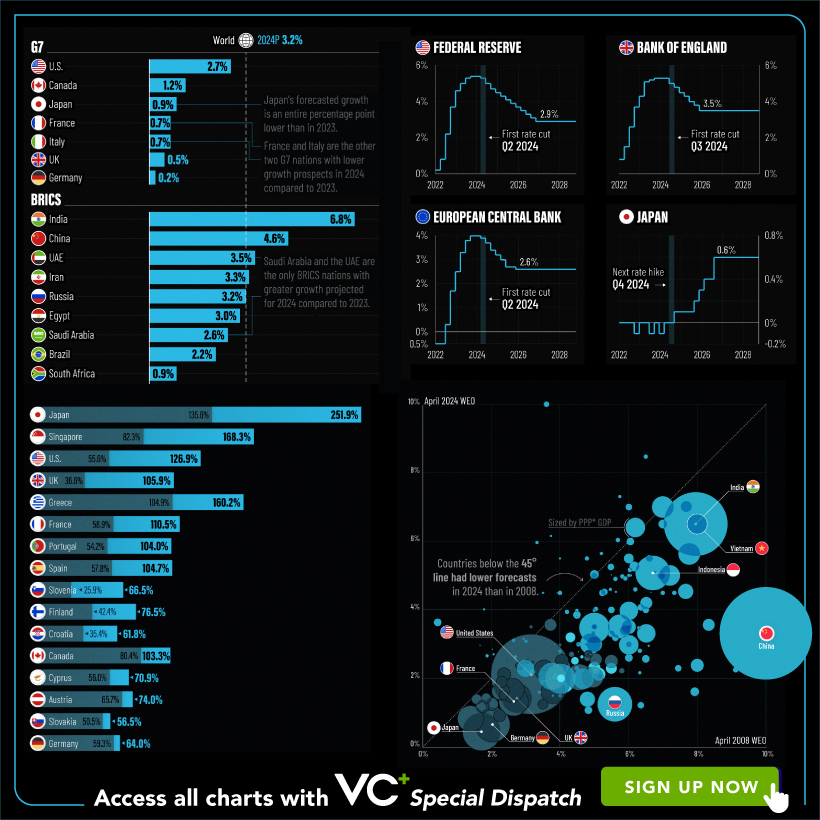

VC+: Get Our Key Takeaways From the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

A sneak preview of the exclusive VC+ Special Dispatch—your shortcut to understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook report.

Have you read IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook yet? At a daunting 202 pages, we don’t blame you if it’s still on your to-do list.

But don’t worry, you don’t need to read the whole April release, because we’ve already done the hard work for you.

To save you time and effort, the Visual Capitalist team has compiled a visual analysis of everything you need to know from the report—and our upcoming VC+ Special Dispatch will be available exclusively to VC+ members on Thursday, April 25th.

If you’re not already subscribed to VC+, make sure you sign up now to receive the full analysis of the IMF report, and more (we release similar deep dives every week).

For now, here’s what VC+ members can expect to receive.

Your Shortcut to Understanding IMF’s World Economic Outlook

With long and short-term growth prospects declining for many countries around the world, this Special Dispatch offers a visual analysis of the key figures and takeaways from the IMF’s report including:

- The global decline in economic growth forecasts

- Real GDP growth and inflation forecasts for major nations in 2024

- When interest rate cuts will happen and interest rate forecasts

- How debt-to-GDP ratios have changed since 2000

- And much more!

Get the Full Breakdown in the Next VC+ Special Dispatch

VC+ members will receive the full Special Dispatch on Thursday, April 25th.

Make sure you join VC+ now to receive exclusive charts and the full analysis of key takeaways from IMF’s World Economic Outlook.

Don’t miss out. Become a VC+ member today.

What You Get When You Become a VC+ Member

VC+ is Visual Capitalist’s premium subscription. As a member, you’ll get the following:

- Special Dispatches: Deep dive visual briefings on crucial reports and global trends

- Markets This Month: A snappy summary of the state of the markets and what to look out for

- The Trendline: Weekly curation of the best visualizations from across the globe

- Global Forecast Series: Our flagship annual report that covers everything you need to know related to the economy, markets, geopolitics, and the latest tech trends

- VC+ Archive: Hundreds of previously released VC+ briefings and reports that you’ve been missing out on, all in one dedicated hub

You can get all of the above, and more, by joining VC+ today.

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoU.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoCharted: Big Four Market Share by S&P 500 Audits

-

Real Estate2 weeks ago

Real Estate2 weeks agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoRanked: The World’s Top Flight Routes, by Revenue

-

Demographics2 weeks ago

Demographics2 weeks agoPopulation Projections: The World’s 6 Largest Countries in 2075

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Top 10 States by Real GDP Growth in 2023